It’s October 5, 2011, and the summit crown of Manaslu is at the top of a short snow couloir on the right of the summit slope. I can see my friend Ian Cartwright waiting at the top, and each time I look up he’s waving at me frantically. I get irritated. I’m climbing very slowly now, but there’s no way I’m going to go any quicker. On the other hand I’m clearly going to reach him eventually. We’ve had several attempts to climb 8000 metre peaks between us, but this is going to be our first summit. We’ve been waiting weeks for our summit window, and climbing for days to get here – I’m hardly going to try and sneak past him by another route now.

When I get to the top of the snow couloir I see why Ian was signalling. He’s holding his oxygen mask to the face of a distressed climber, a bearded man in a red down suit whom I estimate to be about 50 or 60 years old, with a great many sponsors’ logos stitched to his chest. Although hundreds of climbers are sponsored these days, many of them have only written to outdoor clothing manufacturers and been sent free equipment in return. This man has so many logos that either he’s written a lot of letters or he’s a genuinely professional climber.

If he’s in trouble then I’m afraid I’m in no mood to help out right now. I flop down in the snow beside Ian and get my breath back. Chongba Sherpa appears behind me and taps me on the shoulder.

“Look, the summit!”

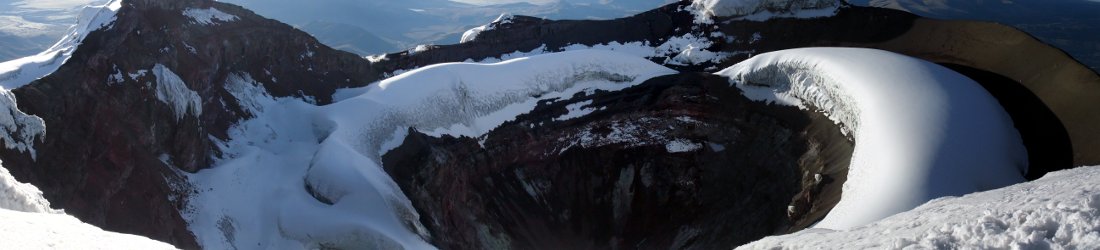

I’m sitting in an area no more than 100 metres in length which houses all of Manaslu’s highest summits. On my right there are two or three small snow domes, and at the far end of a narrow platform of snow is Manaslu’s final snake-like summit ridge, a jagged spine of snow weaving up to a crown of rock bedecked in Buddhist prayer flags. At sea level I could probably run up it in 60 seconds, but at this altitude, exhausted as I am, it will probably take us another 10 to 15 minutes to reach it. In any case, having waited patiently for many weeks then battled hard for five days to get here, it’s my only focus right now – I don’t need any distractions like rescues to carry out, at least not until after I’ve reached it.

After a short rest I stand up and continue, and behind me Chongba persuades Ian to leave the man where he is and come with us.

The bearded man is no longer there when we return from the summit, but we don’t have to descend far before we come across him again. He’s lying across the trail just a short rope length below the bottom of the snow couloir and has perhaps descended 100 metres since we left him. Chongba is leading now, and steps around him despite his protests. As my personal Sherpa Chongba’s responsibility is to get me down from the mountain safely, and he knows that we still have a very long way to go. But there are not many people behind us, and it’s clear we can’t leave the man here. We have to do something to try and establish contact with his team and get some help.

This proves to be a challenge. He doesn’t speak a word of English, and makes no effort to try and understand our questions. We don’t think he has a radio, but we’re unable to find out which team he belongs to. I have a medical kit on me of high altitude drugs, but I’m not sure which one to use. I pull out my radio to call base camp. As a member of the Altitude Junkies expedition team I have a very experienced high altitude expedition leader in Phil Crampton to call upon, who has led around 30 expeditions to 8000 metre peaks. He’s been involved in many rescues at extreme altitude, and is certain to know which drugs to use.

I put the radio to my face, and the man begins shouting at me: “Monica, Monica, Monica, Monica, Monica,” he cries.

I’m a bit maddened by this. I know that Monica is not the name of his wife, but of the only qualified doctor on Manaslu this year. She would certainly know what to do, but she happens to be at base camp, more than 3000 metres below us, and here we are just beneath the summit at 8163m. She’s also a member of a different expedition team, Himalayan Experience (Himex), and my first point of contact is always going to be Phil. I wish the man would shut up and let me think straight so that I can get him the help he needs.

In any case, there’s a bigger problem. We appear to be in a dead zone in terms of radio reception just beneath the summit, and I can hear nothing on my radio even if other people may be hearing me. I will have to guess which drug to administer. I look up to give him the tablet, but now he’s pointing frantically at my face and gesticulating wildly. I realise he wants my oxygen, and it’s not a stupid idea. I really want to use my oxygen myself, but on the few occasions I’ve taken my mask off to drink water and make radio calls, I haven’t had any difficulty breathing. Although it will make descending much harder, it’s clear this man needs it more than I do. The idea worries Chongba, who offers to carry the man’s pack instead, but again the man isn’t listening.

By now Ian has taken over. He’s taken his mask off and is insisting that Chongba help him to give the man his oxygen. Relieved I no longer have to give my own oxygen away, I leave them to it and continue down the mountain. A few minutes later I hear Chongba’s footsteps behind me and we descend together.

The rest of the story I hear second-hand. A little while after we leave them, three more members of the Altitude Junkies team arrive on their way down from the summit: Anne-Mari Hyrylainen, Pasang Wongchu Sherpa, and Kami Neru Sherpa. Anne-Mari has been climbing without oxygen, but she is alert enough to realise the man needs a dexamethasone injection. She is not a doctor, and has never done this procedure before, but while Pasang Wongchu and Kami turn the man over, she clears the air bubbles from the syringe by tapping it on her leg and injects him in the buttock through his down suit. This combined with Ian’s oxygen is enough to get the man moving again. Further down they realise word about the rescue has somehow filtered down the mountain, and they meet a Sherpa from the man’s own team coming up to assist. Between them they are able to get him back to Camp 4, where he recovers further.

Dozing in my tent in Camp 2 that evening, something about the rescue bothers me. Although I’ve heard that High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE) makes people belligerent, the man was not only rude and unhelpful, but seemed to regard our rescuing him as his right, despite the fact that Ian was endangering his own life by giving away his oxygen and descending the rest of the way without it. Could it be that this was simply an inexperienced climber with HACE losing patience with his rescuers, or is there something more to it?

Earlier in the expedition I blogged about what I called parasitic climbers. This had been in reference to two low-budget French climbers who had stolen our tent at Camp 1, but I had gone on to complain about how all of these climbers ultimately relied upon the big commercial expedition teams such as Altitude Junkies and Himex to bail them out when they got into danger, and how such teams are often criticised if they don’t do everything in their power. I hadn’t expected this statement to come true so quickly. Was this bearded man one of the parasites I described, or was he a different calibre of climber?

The following day I got down to base camp and they told me. The man was Juanito Oiarzabal, one of Spain’s most famous high altitude mountaineers. In 1999 he became the 6th man to climb all 14 of the world’s 8000 metre peaks, and only the 4th to climb them all without supplementary oxygen. Even today fewer than 30 people have achieved this feat. And there’s more: Manaslu was his 26th ascent of an 8000 metre peak, a world record for a non-Sherpa.

So what was a man whose record shows him to be one of the top (non-Sherpa) high altitude mountaineers doing at the summit of Manaslu, helpless as a new-born baby, and crying for oxygen like it’s a mother’s breast?

There’s another side to this story. In 2009, at the age of 53, this once-great mountaineer announced that he intended to become the first man to climb all 14 of the 8000 metre peaks twice. Since then he has climbed Annapurna, where he used a helicopter to descend, and Lhotse, where he also needed rescuing. And now Manaslu.

This had been a straighforward rescue, but in some ways it’s lucky it had fallen to members of Altitude Junkies to rescue Oiarzabal on Manaslu. Had the task fallen to Himex, whose team members were also on the summit that day, then their owner Russell Brice would have faced a dilemma. Earlier in the year he had helped coordinate an extraordinary rescue operation on Lhotse involving members of Oiarzabal’s team. Oiarzabal himself required the assistance of a stretcher to get him from the Khumbu Icefall to base camp. The rescue had involved considerable expense and danger to Brice and many other teams, and here was the same man in trouble again on an 8000 metre peak, just four months later.

After returning home and reading about Oiarzabal’s achievements, and above all the phenomenal rescue on Lhotse, I revise my opinion of him. He is no ordinary parasitic climber who steals peoples tents: he appears to be an extraordinary danger to all who put foot on a mountain with him. Friends, family, sponsors: if you speak English and are reading this, please get this man to stop! 26 summits is achievement enough.

But there are heroes and villains in every story. Between them Ian, Anne-Mari and our Sherpa team almost certainly saved Oiarzabal’s life last week. With his illustrious past behind him, he appears to have turned into a monstrous pantomime villain, unable to recreate what he once had, ticking off mountains like Louis Mazzini ticking off his D’Ascoyne murder victims, and bellowing at comparatively novice climbers to part with their life-saving oxygen. Somewhere in the middle are the majority of climbers like myself, whose focus is to reach the summit and then get down safely, putting our own safety firmly before that of any distressed climbers we pass on the way.

Set alongside these people, Ian’s behaviour is all the more extraordinary: forgetting about the summit and administering oxygen to a climber in difficulty even while the summit rises a stone’s throw away, then not hesitating to donate all of the bottled oxygen he was relying on to descend. No sponsorship or summit fame for him. Softly spoken and generous to a fault, he will probably regret me putting his name in print before going quietly back to his job as an offshore surveyor and saving up for his next expedition.

Not only did he reach the summit of an 8000 metre peak last week, but he saved somebody’s life on the way down. Forget that old has-been Juanito Oiarzabal, he of the excessive chest logos who keeps having to be rescued. Ladies and gentlemen I give you Ian Cartwright: a true mountaineering hero.

Comments are closed.