There’s not really a good time of year to visit Chilean Patagonia, as anyone who has been there will know. Lying at the southern tip of South America between 35 and 50 degrees latitude and divided across Argentina and Chile, Patagonia’s geography can best be understood by spinning a globe in your hands and looking at the bottom of it. You will notice most sensible land masses have drifted well north of Antarctica, apart from South America, which appears to be trying to kiss it. In the context of this metaphor, therefore, you can think of Patagonia as a probing tongue, seeking the icy body of the Antarctic Peninsula.

Quite a lot of wind circulates the globe at this latitude across three oceans, and with no continental landmasses to temper it, it slams into Patagonia with its full force, producing severe and prolonged storms and freezing temperatures. Patagonia contains the world’s only ice caps outside the polar regions, and my one and only visit there came in 2003, before I had done any real climbing. I spent a week or so exploring the dramatic rock spires of the Fitzroy area in Argentine Patagonia, and a couple of days chilling out in Ushuaia, the world’s southernmost city on the island of Tierra del Fuego. In those places the weather wasn’t too bad, but the prevailing winds are westerly, which means they strike Chilean Patagonia first, and by the time they’ve crossed the Andes to the Argentine side their storms have been weakened.

When I crossed over the border into Chilean Patagonia to visit the Torres del Paine it was a different story. 48 hours of rain may not sound like very much, but it is when it literally never stops, even for a few minutes. I didn’t realise it was physically possible for the sky to contain that much water. We camped in the rain for two days beside Lago Pehoe, with the dramatic rock spires of the Cuernos del Paine tantalisingly hidden behind mist across the lake. We walked to the superb viewpoint of the Torres del Paine lookout, where we could see bugger all across a dull grey pool as miserable as a wet weekend in Grimsby. There was nowhere to hang our wet things back at our campsite, so each morning we donned the same damp clothing and hoped again for a half decent view of something that day. On the morning we were leaving it dawned clear and we had beautiful views of snow capped peaks across the lake, and I was able to get a few photographs. Of course, I hadn’t bothered taking any pictures in the pissing rain, because I can do that anytime I like back in the UK hills, if photos of grey mist are of any value. This misled one visitor who chanced upon my website and saw the photos that I snatched as we were leaving. They sent me an email enthusing about their forthcoming visit to Patagonia which ended: “I hope we get the same lucky weather you did!” Lucky weather? I felt like going round to their house and flushing their head down the toilet repeatedly for 48 hours, and asking them if they felt lucky now.

But anyway, the purpose of this long rambling introduction is to say that over Christmas I will be returning to Chilean Patagonia for the first time in ten years, and I’m not expecting the weather to be very good.

My aim is to climb the second highest mountain in the Patagonian Andes, 3709m Cerro San Lorenzo, which sits on the border of Argentina and Chile, about 80km east of the southern tip of the North Patagonian Icefield. Also known as Monte San Lorenzo, Cerro Cochrane or its official Chilean name Monte Cochrane, to avoid confusion I’m going to call it Cerro San Lorenzo here, for no other reason than because Monte Cochrane sounds like a posh Irishman. Its severe weather means it has only been climbed a handful of times, but its location on the Andean watershed means that should I be granted an opportunity to reach the summit in clear conditions, I will have fine views across the Argentine pampas to the east, and the Chilean glaciers and fiords to the west.

The mountain was first climbed in 1943 by an interesting character, Father Alberto Maria de Agostini. Born in Italy in 1883, he became a Silesian priest at the age of 26 and emigrated to Tierra del Fuego to become a missionary. Arriving in Punta Arenas in 1910, he joined a community of Salesianos who found themselves striving to protect the culture of the last surviving indigenous communities, the Yamanas and the Onas, tribes which have now become extinct from disease and changes to habitat and lifestyle brought about by European settlers.

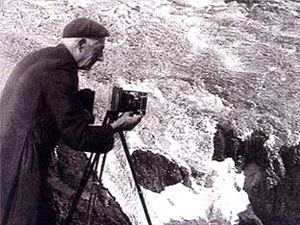

A keen hiker and mountaineer Father de Agostini spent all of his free time exploring the Patagonian mountains of Balmaceda and Paine, and even made a crossing of the South Patagonian Icefield. A talented writer and photographer, he made two films and wrote 22 books, sadly none of which seem to have been translated into English. The reason for this was not through lack of interest among English speakers, but because his panoramic photographs were so ridiculously huge that it simply wasn’t practical to produce any more copies, as this short film demonstrates:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sJVgYdHOOxY

In his later years he worked his way north to the mountains around Cerro San Lorenzo. An intricate peak with a 2000m high, 5km long rock and ice wall on its eastern Argentine side and an easier glacier basin to the west, he spent three years exploring it until he identified a feasible route up. The Agostini Route, which approaches from the west, is still the standard route up, across the seriously crevassed Callaqueo Glacier and up 50 degree ice slopes. Although it’s not an especially technical climb, there is rumoured to be a summit ice mushroom that has prevented a few recent ascents.

Most people serious about climbing mountains in Patagonia spend a few months there and expect to be spending a lot of time enduring storms while they wait for a suitable weather window. Going out there for a two week Christmas holiday I’m realistic about my chances of success. Our itinerary allows us five possible summit days, but I wouldn’t be too surprised if I spend all of them cowering inside my tent. When I tell this to people they think I’m a bit loopy, and wonder why I don’t go somewhere where the weather’s a bit more reliable. I can understand this point of view, but when I consider that many of them will be sitting on their sofas watching endless repeats of the Morecambe and Wise Christmas Special, eating nothing but leftover turkey sandwiches for days and being unable to go anywhere without having to listen to Cliff Richard, Band Aid, Slade, and whatever god-awful X Factor cover version sung in the style of a wailing banshee will be this year’s Christmas No.1, lying in a tent for five days listening to the pitter patter of snowflakes and the howling wind doesn’t seem so bad.

In any case, mountaineering is an activity where rewards have to be earned, but when granted they are worth the discomforts ten times over. Being patient in a tent is something I’m well-accustomed to now, and my Kindle will be loaded with plenty of interesting books to see me through. If that’s what it takes for the small possibility of seeing the rivers, glaciers, ice lakes and rugged peaks of Patagonia from a remote perch miles from anywhere, then I’m happy to take my chances.

Merry Christmas everybody.