Put a bunch of mountaineering legends together in a theatre for an evening, and you’re bound to get a great show, right?

Um … no. Climbing has as much in common with public speaking as it does with hosting a dinner party. I’ve seen some great lectures by big names in mountaineering at the Royal Geographical Society over the last few years, but last week I attended a lecture that was about as slick as a mountaineer’s chin after two weeks in an ice cave. The event First in the Himalaya was organised by Doug Scott in aid of his charity Community Action Nepal, and was based loosely on the theme of first ascents.

The Scottish mountain guide Sandy Allan opened the show. Last year he made an extraordinary new ascent of 8125m Nanga Parbat, the ninth highest mountain in the world, by the 13 kilometre long Mazeno Ridge. The climb took 18 days, and the team crossed 7 peaks over 7000m along the way. After 13 days they ran out of food and most of them opted to escape down a dip in the ridge called the Mazeno Gap, but Sandy and his climbing partner Rick Allen continued across the summit and down the other side, spending the last three days without water. It was an astonishing exercise in endurance and determination by two men in their late 50s, one of the most remarkable Himalayan climbs ever, which even the fittest climbers 20 years younger would have found impossible.

He should have been the most popular person in the room, but he had a strange knack of alienating the audience without really trying. In some ways he was very understated about his achievement, making no attempt to exaggerate the trials he faced along the way, and this may well have been quite endearing had he not spoiled it by making disparaging remarks about his four other companions on the climb, the South African Cathy O’Dowd and three Sherpas called Lhakpa.

He started the presentation with a two minute film which summarised the climb.

“After 13 days, four of the team gave up,” said the narrator.

Gave up? That sounds a bit harsh, I thought to myself, but there was more of this to come.

“We arrived on the ridge, and Cathy and the four Sherpas were a bit discouraged when they realised how long it was,” said Sandy. “But Cathy did really well. I wasn’t expecting her to go so far, and she raised a lot of money for us.”

I probably wasn’t the only person in the audience expecting him to say “Cathy did really well, for a woman.”

A few days into their climb one of the Sherpas broke through a cornice, but thankfully he was unharmed after a 50 metre fall.

“Sherpas are great at load carrying,” said Sandy, “but they’re not very good climbers. By the time we rescued Lhakpa it was late, and we had to stop there for the night.”

He seemed disappointed in his four companions for choosing to descend when they ran out of food, as though he didn’t consider it a very good reason for retreating.

“They had a bit of an epic descent,” he said. “They became lost and one of the Lhakpas broke his leg. Unfortunately Cathy ended up losing her camera, which was a bit of a shame because we were hoping to use her photos.”

At one point Sandy described the Kinshofer Route they used for their descent, as the tourist route.

“I know I shouldn’t really call it the tourist route,” he said, with only a tinge of regret. It’s not a remark that would have won him many clients for his mountain guiding business. Personally I don’t mind being described as a tourist because it’s perfectly true, but I do find it strange that alpinists who climb extreme routes, in common with backpackers bumming around the world, don’t consider themselves to be tourists as well.

By the end of the presentation we were in awe of Sandy’s achievement, but he hadn’t been the most engaging of speakers. Most presenters try to get the audience laughing with the occasional joke, but the theatre had been as quiet as a library during a total eclipse. In fairness to Sandy, he supports himself by guiding and probably doesn’t speak that often. It’s a privilege to hear about an ascent as outstanding as this one from the horse’s mouth however it’s delivered, so I shouldn’t be too critical. My friend Dan summed the talk up when he turned to me at the end.

“That was an amazing climb,” he said, “but he’s not the kind of guy you want to go for a pint with!”

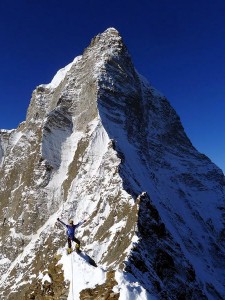

Luckily Sandy was followed by Mick Fowler, the current President of the Alpine Club, who told us about his first ascent of the Prow of Shiva, a 6142m peak in Ladakh, northern India. It was a very different presentation by a very different man. A tax inspector by profession, Mick Fowler works for HM Revenue and Customs for most of the year, and during his holidays he forges bold new routes on sight up mountains in the Himalayas.

He outlined his criteria for choosing a climb: a first ascent of a mountain, or a new route, on a difficult line, in a remote part of the world with cultural interest. Oh, and you need to be able to climb it during a 4 week holiday off work.

He was a natural speaker, who came across as an ordinary guy who happened to do something extraordinary in his spare time, and he cracked jokes throughout. He illustrated his craving for places with cultural interest by showing us a couple of photos: the first of a man selling false beards outside the Red Fort in Delhi, and the second of a cart so overloaded it had toppled over at the back, causing its horse to hang in mid air. We roared with laughter.

While Nanga Parbat is one of the world’s best known mountains with a rich climbing history, Mick Fowler’s peak Shiva is virtually unheard of, with very little information available. He found a Russian climber who had photographed it and advised him it would be a very difficult climb.

“This is what he told us,” said Mick, pulling up a slide containing the quotation “Frankly I cannot imagine how you will do it.”

He showed us some video footage of the drive in, along a scary road weaving hundreds of metres above a precipice. He described their trek to the base of the mountain as luxurious, with a liaison officer, a cook and porters provided by a local agent. It took him and his climbing partner Paul Ramsden 9 days to traverse Shiva, up the almost vertical northeast buttress, bivouacking on tiny ledges, and descending its gentler far side.

“The lower snow slopes were really bad, but the rock above was very solid granite,” he said.

We were treated to some amazing photos of the pair on the buttress, and video footage shot from their camps, with a sea of Himalayan peaks on the skyline. It was a climb oozing with the spirit of adventure, completed by two friends with no corporate backing and very little media publicity. It was very refreshing, and undoubtedly the highlight of the evening.

After the interval there was another short interlude as our host the mountaineering superstar Doug Scott tried to auction some signed prints in aid of his charity Community Action Nepal. There were some stellar signatures: Reinhold Messner, Peter Habeler, Tom Hornbein, Walter Bonatti, Chris Bonington, George Band, Joe Brown. I’ve seen him do this a few times now, and they sometimes sell for hundreds of pounds, but today we were all skinflints. A gentle breeze blew across the auditorium and some tumbleweed wafted onto the stage. In the distance I swore I could hear a church bell tolling. Of the sixteen prints auctioned, thirteen didn’t attract a single bid. Three sold for the minimum price to people who seemed reluctant. One of them quibbled over the small matter of £25. It was a bit embarrassing.

Doug seem unfazed, and I expect this happens to him often. “Thank you for your forbearance,” he said at the end.

The next speaker was announced, an Austrian climber called Robert Schauer who I must confess I had never heard of, but he made the first ascent of the West Face of Gasherbrum IV in 1985.

A grey-haired man walked up to the stage and said: “My computer is just rebooting. I think it is best if Kurt goes next and I will talk after him.”

He walked to the front of the audience and pulled Kurt Diemberger out of the front row, an absolute mountaineering legend, now in his 80s, who made the first ascent of Broad Peak in 1957 and the first ascent of Dhaulagiri in 1960, both 8000m peaks. He was the man we had all come to see, and Robert Schauer was making a big mistake, but we didn’t yet realise quite how big.

In mountaineering terms Kurt Diemberger’s presentation was a bit like an expedition which spends most of its time stuck at base camp waiting for a weather window. Every so often it makes a brief foray into the icefall, but on each occasion foul weather forces it back to lick its wounds.

He was supposed to be talking about the first ascents of Broad Peak and Dhaulagiri, but he spent the first five minutes telling us how difficult it is to fit an account of two epic expeditions into just one hour. By the time he finished there were only 55 minutes left. He quickly made up for it by showing five minutes of archive video footage of the Austrian team climbing Dhaulagiri. That was Dhaulagiri done, and he had 50 minutes left to talk about Broad Peak and other things. He started with the other things. There was a photo of him on the summit of Shartse sporting an ice beard after another first ascent. He described how a full traverse of Shartse, Lhotse Shar, Lhotse and Everest up the Southeast Ridge and down the West Ridge, was one of the last great problems in Himalayan mountaineering. This may be true, but it wasn’t what we came to hear him talk about. We saw a photograph of a man hammering in a peg with a big mallet (his father apparently), another of snow flakes, some ice crystals, and a page from an old manuscript with drawings of climbers in the margins. Although his English is good he has a very thick accent, and I probably wasn’t the only person in the audience who had no idea what he was talking about.

He finally moved onto the first ascent of Broad Peak, a story I’m more familiar with, and therefore found easier to follow. Kurt, Marcus Schmuck, Fritz Wintersteller and Hermann Buhl, teamed up to make an alpine-style ascent, carrying all their own kit and climbing the mountain in a single push. Buhl was the experienced old stager who had already made the first ascent of Nanga Parbat. He was supposed to be climbing leader, but the much younger Schmuck had done much of the fundraising, and was nominally appointed full expedition leader. Schmuck, of course, is a Jewish word for the part of a penis which is discarded after a circumcision, and in the light of what was to come, Kurt may have found this appropriate.

“Never should this system of two leaders be tried again,” he said.

The team split into two competing factions, Schmuck and Wintersteller, and Buhl with the more loyal Kurt. On summit day Buhl was slower than the others and dropped behind. The other three reached the summit first. Kurt climbed onto a cornice to take some photographs, and by the time he climbed down the other two had left.

“So I thought there would be no photo of me on the summit,” he said, in obvious annoyance.

But on the way down he met Buhl coming up, and returned to the summit with him. After they returned to base camp the two pairs split up and went off climbing separately. 18 days after summiting Broad Peak Kurt was climbing 7665m Chogolisa when he looked round and noticed Hermann Buhl was no longer behind him. He turned and retraced his steps until he came to a place where Buhl’s footprints came to an end at the edge of a broken cornice.

It was obvious Kurt idolised Hermann Buhl and was angry about the way the other two had behaved on Broad Peak. Although these events happened 56 years ago, he spoke like it was all still fresh in his mind. It was as though the scars from Buhl’s death were still healing.

But there was more. The last ten minutes of his presentation were not about Dhaulagiri, as we were expecting, but his ascent of K2 in 1986, when his soulmate and climbing partner Julie Tullis died during a storm. It was all quite emotional and hard to follow. He has achieved a great deal in his life, but I was left feeling the things he remembers most are these two terrible tragedies. If I don’t see him again I will remember him waving to the audience as he left the stage to a standing ovation and departed to catch a train.

It remained for Robert Schauer to end the show with a moment of pure farce. It was already 9.30pm, the time the evening was billed to finish, and the headline speaker had gone. Robert would need to be good to keep us in our seats.

“I am sorry I was not ready earlier, but it is better this way,” he said as he arrived on stage.

His computer had now been rebooted, but he hadn’t fixed the aspect ratio. The first film he showed was chopped off at the top and bottom of the screen. He looked angry, and left the stage with the film still playing. Two minutes later the film stopped and Robert’s voice came over the speakers.

“I am sorry, but I cannot show you the film like this. Please bear with me, and take a break for a few minutes.”

The lights came on and people started leaving the auditorium in droves. I looked across at Dan.

“Do you want to stay, or shall we go to the pub?”

It was getting late. We had been there for three hours and I needed something to eat.

“Let’s stay and see what happens. I feel really sorry for him,” said Dan.

Five minutes later, Windows Desktop was still on the big screen and the Control Panel had been opened several times to no avail. I felt like I was back at work and somebody had phoned up IT technical support at the start of a meeting. When the words Windows is restarting appeared on the screen it was too much for me.

“F— it, Dan, let’s go. I can’t take any more of this,” I said.

Perhaps I was being unfair but I felt like I’d had my money’s worth. We’d seen three great mountaineers, one of whom was even a very good speaker. It had been a bit frustrating in places, but you don’t always reach the summit.

I don’t know whether Robert Schauer’s presentation was worth staying for, or how many people remained to see it, but we did have a very enjoyable pint afterwards. I’m not the world’s best public speaker myself, but I can offer one piece of advice: if you usurp the headline act, you’re taking a bit of a risk.

HI Mark, I have just come across your blog ( 23 /06/2014)…. I am so disappointed to read in your blog that you think I was negative about the Sherpas: Rangdu, Zarok, Nuru and Cathy.. Its never has been or ever will be my intention to give that impression as it is simply not true and such thoughts have never entered my mind. So, I have no idea why you thought the things you say in your blog. I have no idea how my words could be misconstrued that way, but I must have said something badly and I do apologise. I would like the opportunity to talk with you as perhaps you can help me understand what mistakes I made to have left you with such a negative impression. I am terribly sorry.

Please try and get in touch. I will try and contact you too.

Even although your feedback is terrible negative towards me, I can assure you there was no negativity intended by me and I hope I can improve in the future. Please try and get in touch with me as obviously there must be room for improvement and I can hopefully learn from this event. I shall try and contact you.

Thanks

Sandy

Hi Sandy,

That’s a very touching response and in that case I am very sorry if my review of the lecture has upset you so much. The internet being what it is I always make the assumption that whoever I write about will read it eventually, so even when I’m being critical I try to be fair. I don’t always get it right, and in this case it looks like I haven’t succeeded.

When I spoke to my friend after the lecture we both came to the conclusion that it looked like you were being critical of Cathy and the Sherpas’ decision to retreat (and overall resilience). I should have given you the benefit of the doubt and I can see by your reaction that you are genuinely upset that we thought that.

It was a privilege to have had the opportunity to hear you talk about the climb, one of the great Himalayan first ascents. There’s no need for you to worry too much about anything I said here, and I’m sure not everyone in the theatre that evening saw things the way I did. It was a bit of a strange evening; Mick Fowler’s was the only lecture that seemed to go very smoothly. I’m sure it can’t be easy, and it’s all very well for us to be critical from the comfort of the audience!

Best of luck with future climbs and lectures, and my apologies once again.

Regards,

Mark.

hello Mark,

you come across as a know-it-all pompous judgmental windbag!

I’ve never met you though, but I wouldn’t recommend your blog to anyone.

Sandy Allan, on the other hand, I have known for around 36 years, and he is one of the most genuine guys around. It’s disgraceful how you have slandered him in your blog.

yours sincerely,

Asty Taylor

I’m not sure what you’re hoping to achieve by adding an abusive comment to the amicable messages Sandy and I exchanged above, but if you want me to pick up my sword again then I will.

I met Sandy a couple of times while he was guiding and on the first occasion I have to admit I found him decidedly prickly and difficult. On the second occasion however, he was extremely kind and could not have been more helpful. If he is your friend of 36 years then I expect the Sandy you know is the second one, but if he’s not like that with everyone all of the time then that’s OK because he’s only human, just like the rest of us.

Whether you are a public speaker or a writer you need to have a thick skin, because like it or not people are going to form opinions about you, and they won’t always be to your liking. From his message above I believe Sandy understands this. What I have written are my honest impressions of a talk I went to see. Those impressions may be right or they may be wrong, but they are honest. If I believe I have been too harsh then I’m happy to hold my hands up and say so. As you can see, I have done this.

This is not slander any more than it’s slander for you to call me a pompous windbag. You are entitled to your opinion. I am aware my blog is not everyone’s cup of tea and I’m comfortable with this. It would have to be pretty bland if I tried to please everybody, and if you don’t like what I write then you don’t have to read it.

Hello,

i appreciated the honest and descriptive review of the presentation.

And I have met Sandy Allan and he is rather opinionated and condescending to women from all I have seen.