The headline Mallory’s body discovered on Everest in 1936 appeared widely on social media sites last week. People were sharing an article by the mountaineering journalist Ed Douglas which appeared in the Guardian/Observer, believing that major new revelations had emerged about George Mallory, who went missing in mysterious fashion on Everest in 1924.

But George Mallory wasn’t the main subject of this story, and the story of his body being “discovered” wasn’t really a story at all, but a clever piece of marketing. But since the real subject of the story was arguably a far more interesting character than Mallory, I’m going to play along with the marketing and tell you a little bit more about him.

Contrary to the headlines, George Mallory’s body wasn’t discovered on Everest in 1936 at all. It was just that one of the expedition team members that year, Frank Smythe, thought he had seen a smudge somewhere on the North Face through a telescope, which he thought might have been a body. Smythe was at base camp at the time, 16 horizontal kilometres north and 3 vertical kilometres below, which by careful application of Pythagoras’ theorem tells us he was 16.3 kilometres away. You may disagree, but in my book that doesn’t really amount to a discovery.

Smythe may have been right though. He was scanning the slopes below where an ice axe belonging to Mallory or his climbing partner Sandy Irvine was found in 1933. In 1999 Mallory’s body was found in that very spot, which means Smythe’s “discovery” doesn’t tell us anything new, other than that he had very good eyesight.

The real story that appeared last week wasn’t about George Mallory, but Frank Smythe. His son Tony Smythe has just published a biography of him called My Father Frank, and during his research he discovered a copy of a letter Smythe had written to Edward Norton, leader of the 1924 expedition when Mallory and Irvine went missing. In the letter Smythe revealed what he had seen through his telescope while scanning the slopes, but he entreated Norton never to tell anyone because he expected the press would make an “unpleasant sensation” about it.

Goodness me, the press make an unpleasant sensation about dead bodies on Everest (like this, for example, and this, as well as this, and this) – surely not?

But anyway, that’s by the way. It was a clever piece of marketing by Tony Smythe to draw attention to his biography by revealing new revelations about George Mallory, and I’m all in favour of it. Frank Smythe is something of a forgotten figure of Himalayan exploration, and his story could do with a bit of a revival.

It wasn’t always so. These days there aren’t many mountaineers who are household names outside of the climbing community. The last British mountaineer to hold that status was probably Chris Bonington, who enjoyed sufficient fame to have entire TV series commissioned in the 1970s and 80s. But in the 1930s Frank Smythe and a handful of other climbers enjoyed that status, largely due to public interest in Everest expeditions, but also because of his writing. In an age when many mountaineers were either amateurs with a profession or gentlemen with an independent income, Smythe was one of the first to fund his expeditions through publicity, which for him meant writing and photography. He began by rock climbing in North Wales and progressed to alpine mountaineering in Europe, but he was best known as a Himalayan explorer.

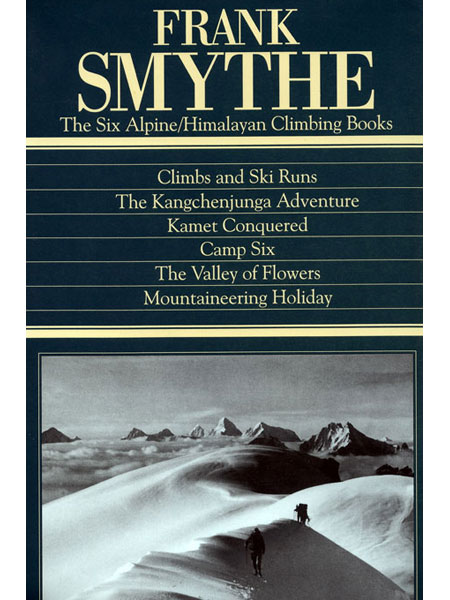

I first heard about him when I read the compendium of his best known works, The Six Alpine/Himalayan Climbing Books, published by Baton Wicks. Four of these cover some of his most engaging adventures in the Himalayas.

In 1930 he was invited to join an international expedition to climb Kangchenjunga, led by the Swiss-German Gunther Dyhrenfurth, one of the earliest attempts on an 8000m peak. It was a badly planned expedition which involved numerous porter difficulties during the trek in from Darjeeling to Nepal. Dyhrenfurth chose to attack the difficult and dangerous ice cliffs of the Northwest Face, but they were driven back when most of the team were caught in an avalanche and were lucky to suffer just one casualty, the Sherpa Chettan. As a consolation they made the first ascent of 7483m Jonsong Peak, which at the time was the highest summit ever climbed, and perhaps uniquely for a Himalayan expedition Smythe celebrated another first ascent, 7154m Nepal Peak, by drinking champagne and playing a mouth organ. But the expedition’s most enduring legacy was Smythe’s book about it, The Kangchenjunga Adventure.

In 1931 Smythe led his own Himalayan expedition to the Garhwal region of India north of Delhi. His team, which included another giant of 1930s Himalayan exploration, Eric Shipton, made the first ascent of 7756m Kamet, once again the highest summit that had ever been climbed. Smythe’s book Kamet Conquered describes this expedition. He is best known for his three expeditions to Everest in 1933, 1936 and 1938. During the first of these he reached a record altitude of 8565m while climbing alone after his partner Shipton turned back ill. While descending exhausted from this ascent he started hallucinating flying saucers above the North Ridge.

“I saw two curious looking objects floating in the sky. They strongly resembled kite balloons in shape, but one possessed what appeared to be squat, under-developed wings, and the other a protuberance suggestive of a beak. They hovered motionless but seemed slowly to pulsate, a pulsation incidentally much slower than my own heart-beats … My brain appeared to be working normally, and I deliberately put myself through a series of tests.”

Yeah, right Frank. Luckily this particular incident is rarely mentioned, and he is more famous for the altitude record, which he described in his book Camp Six. Smythe’s best book is The Valley of Flowers, about a three month exploratory trip to Garhwal pressing wild flowers (no, seriously). He restored his manhood by also making first ascents of Mana Peak, Deoban and Nilgiri Parbat.

He died tragically young at the age of 48, when he contracted malaria during another visit to Darjeeling in 1949. Tenzing Norgay, who had climbed with him during the Everest expeditions of the 1930s and was in Darjeeling at the time, described his sad deterioration in his autobiography Tiger of the Snows:

“He said to me, ‘Tenzing, give me my ice axe.’ I thought he was joking, of course, and made some sort of joke in reply. But he kept on demanding his axe, very seriously; he thought we were up in the mountains somewhere; and I realised that things were badly wrong with him. Soon after, he was taken to hospital, and when I visited him there he did not recognise me, but simply lay in his bed with staring eyes, talking about climbs on great mountains.”

Tenzing also described Smythe as “the most famous of all Himalayan mountaineers”. It’s no longer true, and even now he’s probably not as well known as his contemporaries Shipton and Bill Tilman, the other two leading lights of the 1930s Everest expeditions. His memory is due a revival. I expect many people will look at the headlines and wonder what it means for the legend of Mallory and Irvine, and whether they reached the summit of Everest. What they’re supposed to be doing is buying a copy of Smythe’s new biography. Better still, pick up The Six Alpine/Himalayan Climbing Books, a true doorstep of a tome that will keep you entertained beside the fire or inside your tent for weeks. You can even put it in your backpack and head for the mountains. Weighing in at a solid 1½ kg, it will be good training for you.

As usual a very interesting piece of writing. Although short in length it managed quite ably to carry my mind back to the 1930’s. Although I was born in the 30’s I was not of an age where my mind was fixated by these wonderful far away places. Sadly I am also one of the many who have only heard the name Frank Smythe mentioned in passing and dwelt in detail on Mallory and Irvine. I often wonder how many more unsung heroes there are in the passing years and fail to obtain recognition. On the other hand many of these brave folk are quite happy to stay quietly in the shadows.Thanks again Mark for providing me with another really interesting piece of the jigsaw.. Cheers Kate

Mark, thanks for the heads-up on this remarkable man. The Mrs and I are considering the Kangchenjunga Circuit next fall. Have you any experience or info on this route? Other than JG, any recommendations on capable operators? Sorry for going OT…

I get the Responsible Travellers to arrange the logistics for most of my Nepalese treks and climbs (http://www.theresponsibletravellers.com). They can also fix you up with an NMA climbing guide if you’re thinking of doing any trekking peaks. They’re non-profit and proceeds go to various Nepalese charities including CHANCE, a charity I support as a trustee (http://www.educationfornepal.org).

I’ve not been to the Kangchenjunga area myself, but would very much like to one day.

Thanks Mark, I will check them out 🙂

I enjoyed reading the above articles. I am 72 now and grew wanting to climd Everest at least in my dreams. However now I am confused as to how every man and his dog can now climb Everest, can you explain how this is? Feel all adventure is gone. Now people run up the Eiger.

No more comments to add.

Pingback:10 Amazing Natural Wonders to See Before You Die | trendy10.in

Having read all of his books Alpine and Himalayan (except the flower book) Frank Smythe was a true Titan of the 1920,s and 30,s mountaineering scene. His many explorations and the eloquent books of them in the uncharted Himalayas with the cream of British and European mountaineers make absolutely riveting reading. The porter dropping and losing the gramophone records (and being roundly berated for it) during the Kanchenjunga book raised a smile and demonstrated just what these enormous expeditions comprised. His books are written magnificently well. A true unknown British mountaineering great !.

Hello

I have two books by Frank Symthe

Over the Tyrolese Hills & The Spirit of the Hills both published 1935 but inside one of them is a handwritten note tilted Refelections on the summit of the Mana Peak by F S Symthe ,The Valley of the Flowers page 236 .

After reading your blog about his son Tony writing his biography I wondered if he would like this note ? I don’t know how to get in touch with him but thought you maybe could .

That’s a nice thought. I’m guessing the best way to get in touch with him is through his publisher Vertebrate. Jon Barton, the MD, is usually quite responsive about this sort of thing:

https://www.v-publishing.co.uk/books/categories/baton-wicks/my-father-frank.html

Mark,

Norton reached 8570 meters, according to Wikipedia. This is five meters higher than Smythe climbed, right, on Everest? Why is Smythe a record holder? Regards, John Wysham

Have you read my more recent post about Frank Smythe here?

https://www.markhorrell.com/blog/2020/his-father-frank-smythe-biography-of-a-himalayan-legend/

In the relevant paragraph of Tony Smythe’s book, he says (on p.183): “his [father Frank’s] highest point was calculated as 28,200 feet, or about 8,600 metres”.

It’s not clear what the source is for the assertion in the Wikipedia article that it wasn’t surpassed until 1952. My feeling is that all of these very precise altitudes cited in the 1920 and 30s need to be taken with a pinch of salt anyway because the altitudes were taken using aneroid barometers, which aren’t that accurate. A better way to assess who went further is probably going to be by reading their descriptions.

Mark – you’ll be sorry to hear that Tony Smythe passed away on February 14th in Kedal.

He was 89. and had been in a care home for several years. The rope-mate of my youth.

Sad news. He lived an interesting life. I enjoyed his book about his father as much as I enjoyed his father’s own books. He must have been fun to climb with.