It’s now a week and a half since a 7.8-magnitude earthquake rocked Nepal, killing over 7,000 people, injuring tens of thousands more, and making hundreds of thousands homeless.

The earthquake caused significant damage on Everest, triggering a catastrophic avalanche which swept through base camp, obliterating its entire middle section and killing 20 people. More avalanches in the Khumbu Icefall erased the climbing route so carefully prepared over the previous weeks, leaving 170 climbers stranded in the higher camps, who had to be airlifted to safety by helicopter a few days later. It was far more devastating than the huge avalanche I witnessed sweep across the Khumbu Icefall last year, which killed 16 and was by some margin Everest’s most deadly climbing accident.

What happened this year can’t really be described as a climbing accident though. Nepal has been expecting a big earthquake for 80 years. It sits on the edge of one of the world’s most unstable fault lines which has pushed its mountains 9km into the sky. International agencies have been pouring resources into disaster preparedness for years, but when the inevitable earthquake finally came there wasn’t much anyone could do other than hide under the table and hope the damage wasn’t too severe.

In this context what happened on Everest is pretty irrelevant, and had nothing at all to do with mountaineering (which isn’t to say it wasn’t tragic and terrifying for everyone involved – my partner Edita was at base camp when the avalanche struck, and for four hours that Saturday I had no idea whether she was dead or alive).

Despite this it wasn’t long before the climbing community started bickering about Everest again, focusing on details that would seem extraordinary to normal people. Some of them questioned whether helicopters should have been used to rescue the 170 stranded climbers from Camp 1. They said the choppers should have been deployed elsewhere, and the climbers left to climb their way to safety. The argument, from what I can tell, is that despite having travel insurance for just such an eventuality, they should have been willing to martyr themselves for the greater needs of Nepal.

I don’t need to dwell on this too much, since it’s based on ignorance of both the Khumbu Icefall and Everest climbing history (not to mention the effect of the earthquake), and comes from the Nigel Farages of the climbing community [*]. What normal person with a gram of compassion could possibly question whether or not rescuing 170 people – black, white, rich or poor – from certain death in the space of three hours is a good thing? I’ll give them the benefit of the doubt and assume they were just failing to see the bigger picture, and weren’t being inhumane. The alpinist Freddie Wilkinson wrote a good summary of the debate for the Foreign Policy website, which helps to explain why it was even discussed.

There was more recrimination when members of the Himex expedition team insisted they should be allowed to resume their climb a few days after the tragedy. It seemed they may have badgered their leader Russell Brice to talk the Nepalese government into reopening the route up the Khumbu Icefall. It shouldn’t be too surprising to learn there are climbers who give other Everest climbers a bad name, or that the Nepalese government change their minds if provided with a financial incentive. Russell Brice’s season had been more difficult than most. He lost three clients trekking in Langtang, and did the only thing he could by sending his angry clients home.

But anyway, enough of that. While all this hot air was being spouted on western social media, the Nepalese themselves have been quietly rebuilding their lives, and as the one-man UK comms team of a charity which operates in Nepal, I’ve been given a privileged insight into it.

Our charity CHANCE, who provide sustainable aid for education in Nepal, was thrown into crisis mode. We’ve never done disaster relief before, and our initial response was to direct UK donors wishing to donate to the emergency response to the main DEC Nepal Earthquake Appeal. That soon changed.

Over the last three years we have been introducing the Duke of Edinburgh’s International Award (DofE) across Nepal, by encouraging schools and young people to participate, and by training award leaders. Our Nepali management board for the Award have all been getting their hands dirty helping out with the crisis response, and I believe most if not all of their work has been improvised over the last week and a half, in response to the needs of ordinary people affected by the earthquake.

I’m now connected to most of them on Facebook, and I’m in awe of the work they’ve been doing. Here’s just a brief selection of the dozens of posts that have been popping into my newsfeed every single day.

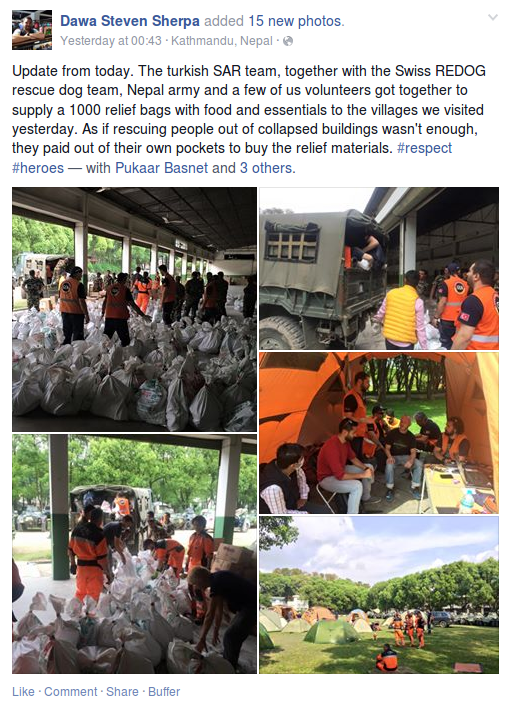

DofE Nepal patron Dawa Steven Sherpa, who is managing director of the expedition operator Asian Trekking, and himself an Everest summiteer, was coordinating logistics for supply vehicles. On one occasion he went out with a Turkish search and rescue team supplying relief bags.

DofE board member Sumnima Tuladhar works for CHANCE’s local partner organisation CWIN, who help to implement some of our projects. She sourced hospital information to locate displaced children, and then sent out youth volunteers with supplies.

Chandrayan Shresta is a school principal and our DofE national programme manager. That didn’t stop him getting his hands dirty as a volunteer for CWIN digging toilet pits.

Perhaps most impressive of all in terms of rapid response was DofE board member Suman Shakya, who with five other volunteers on Monday 27 April set up a movement called Nepal Rises to mobilise volunteers to help with the relief work. Here’s a nice infographic summarising their impact by the end of the week.

Our impact yesterday. A week has passed and everyone has come together. The need is there and so are we. pic.twitter.com/fZ5rex5wxm

— Nepal Rises (@nepalrises) May 3, 2015

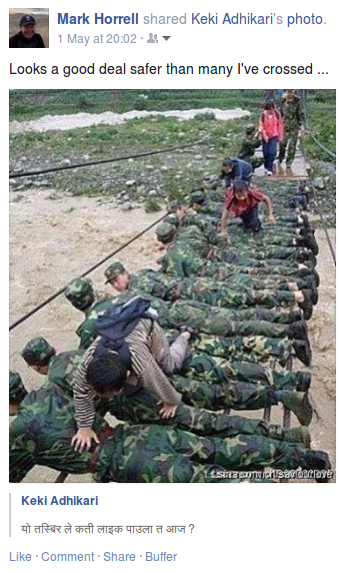

And then, of course, existing institutions have been improvising too, and lifting heaven and earth to help out, including the army with this man bridge. 😉

I don’t want to make out everything in the garden is rosy; this is far from being the case. Much of the response has been concentrated in the Kathmandu Valley, and there are still a great many people affected by the earthquake in remote parts of Nepal who have not yet been reached. The financial environment is challenging. The government made an announcement that aid had to be channelled through its relief fund, which caused confusion and anger. Bureaucracy remains impenetrable, and aid workers complain of supplies being delayed at the airport and border crossings as paperwork is completed by the book. There have been reports of people being charged duty on their supplies. These are significant barriers.

I’ve not been a trustee for very long and I’ve learned a lot in the last few days. I expect those of you who work in disaster relief or international development will have known this all along, but it’s been an eye-opener for me. The initiatives have not come from foreign aid organisations, providing the resources and dictating what needs to be done. The ideas and the actions have come from the Nepalese themselves. They have identified the needs, and as long as we can satisfy ourselves those needs are genuine our responsibility as trustees of a western charity is to raise the funds and provide the supplies.

There have been lots of gloomy stories about Nepal in the last week or so, but if it’s going to recover from this tragedy then it will require hope, not despair.

Many of the best things in life are born in adversity. Watching all this from afar has been an uplifting experience for me. It tells me that Nepal’s future can be bright. The country is full of industrious people and amazing natural resources. There is a huge amount of goodwill from the outside world, and the only thing standing in the way of its development are the greedy politicians who have been holding the country back through incompetence and corruption. If they can somehow be pushed aside by the collective will of its people then much good can come of this terrible natural disaster.

It has also taught me that we can bicker all we like about Everest, but its future will ultimately be decided by Nepalese. And that’s exactly how it should be.

[*] A divisive politician standing in tomorrow’s general election here in the UK. [Back]

In its own ironic way, this natural calamity has helped to shift the focus from the generally ego-driven obsession of mountain climbing (of which I too am guilty!) to a more compassionate approach to the people who live amongst the greatest peaks in the world.

Please make correction. The picture showing the human bridge is not from Nepal. It was from China some years back.There are few really touching pictures being shared on social media that are not actually from recent earthquake.

Full marks for spotting the deliberate mistake, though you’ve been marked down for missing the humour!

The one light-hearted photo doesn’t alter the message of hope contained within the four serious ones, and I beg to differ they’re not touching. I’ve made the “correction” you requested, and added a winking man for clarity. 😉