Four months after an unusually deadly Everest season, another tragedy in the Himalayas has focused the attention of the world’s media on the sport of high altitude mountaineering. Because mainstream media only seems interested in mountaineering in the event of a disaster, coverage is often negative and poorly informed. I’m going to try and provide a mountaineer’s perspective on what happened last Sunday night on Manaslu, based on my understanding of the many conflicting reports in news articles and expedition blogs.

What happened on Manaslu?

At approximately 4.30am last Sunday, a serac (or wall of ice) collapsed on 8163m Manaslu in Nepal, the world’s eighth highest mountain, while climbers were camped on the slopes below. The serac triggered an avalanche which swept down a 500 metre snow slope on the main climbing route, burying and uprooting tents and throwing them down the mountain. About 30 people were inside their tents sleeping at the time and were caught in the avalanche. While most survived with varying degrees of injury, at the time of writing 8 are confirmed dead and 3 more are missing, presumed dead. Friends of mine from the Altitude Junkies expedition team were camped beneath the avalanche when it struck and described being catapulted around several times before coming to rest five metres away in a shredded tent. They had to get up in the dark and retrieve all their equipment from the snow (#17 in their expedition dispatches). Thankfully all of them survived with only minor injuries, but particularly poignant for me was that almost a year ago to the day I was camped in that very same spot myself, with many of the same people who were there last Sunday, on my own summit push on Manaslu. I will try and reconstruct what may have happened from some of the photographs.

As you can see from the above photograph, there are 4 camps above Base Camp on Manaslu en route to the summit: Camp 1 at 5800m, Camp 2 at 6400m, Camp 3 at 6800m and Camp 4 at 7450m. Between Camps 1 and 2 is the most technical part of the route, through a maze of steep crevasses and seracs. From Camp 2 to Camp 3 is a broad and relatively gentle snow slope. Above Camp 3 is a wide col (the North Col) between Manaslu and one of its satellite peaks. The climb above the North Col involves two exhausting snow slopes separated by a short wall of seracs.

It was a serac somewhere above Camp 3 which caused the avalanche. Climbers at Camp 3 were worst affected, and include all of the fatalities. Climbers at Camp 2 were relatively safe from the main body of the avalanche, but because it was such a big one, they were struck by some of the debris and wind blast from it. It was here in Camp 2 where my friends in the Altitude Junkies team found their tents lifted up.

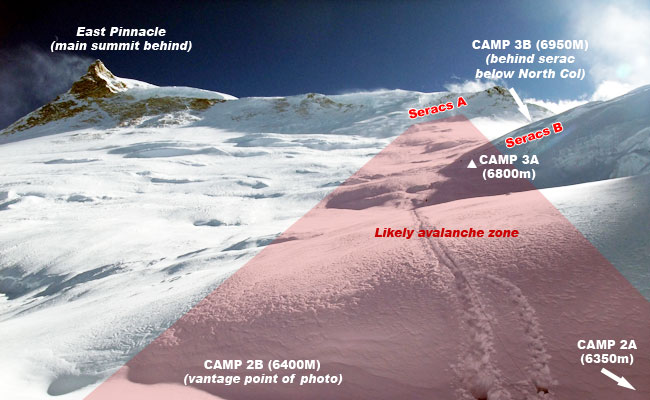

In fact the situation is a little more complicated, because both Camps 2 and 3 are divided, so in the next photograph I will look at this area where the avalanche occurred in more detail.

Reports suggest the serac which broke off was huge, up to 600 metres across. There are two possible candidates for this. When I first heard about the avalanche, my initial thought was the seracs marked B in the photo. These seracs were considered to be safe, and Camp 3A sits directly below them, sheltered from the high winds that buffet the higher camp 3B just below the North Col. A collapse here would very likely have wiped out Camp 3B entirely, leaving no survivors. In fact, reports suggest the serac which collapsed was at around 7400m, meaning it is likely to be from the serac field marked A on the photo which it’s necessary to pass through on the climb from Camp 3 to Camp 4. This area of seracs stretches up to the small dark triangle of rocks beneath Camp 4, which you can see in the top right of the above photo. Serac field B would have provided some shelter for Camp 3A, but not much given the scale of the avalanche. Camp 2B on the other hand, has some protection from avalanche due to the presence of a large gully between the snow slope above and the position where the photo was taken from, which would have funnelled the snow in the direction of the arrow down to Camp 2A. This gully also passes to the side of Camp 2A, and climbers here were apparently unaffected by the avalanche.

Incidentally you can see tiny black dots in the pink area between Camp 2B and 3A in the above photo which are people climbing, giving you an idea of the size of the snow slope.

The following photo was taken from Camp 3A and shows climbers leaving on their way up to Camp 4. As you can see, a 600 metre chunk of ice breaking off from the serac field in front of them would have put them almost directly in line of any resulting avalanche. The photo was taken last year, so there may have been more ice last week, but you can clearly see a bundle of broken ice beneath the ridgeline directly above the heads of the leading climbers. Any of this jagged broken-looking ice is a likely candidate for the serac which collapsed.

Finally on this subject, I took some video footage of the avalanche zone during my summit push, which may help to give an idea of the location. I describe the snow slope above Camp 2 at 7:17 in the video. There is also some brief footage of Camp 3 at 9:45.

Should expeditions be abandoned?

While we can never forget the tragedy which has occurred, ironically an avalanche of this scale will have made the mountain much safer for subsequent attempts. While many climbers have now gone home, others are still there, hopeful of another chance to climb the mountain. Manaslu gets an enormous amount of precipitation this time of year, and prior to the avalanche climbers waited for many days at Base Camp while it snowed. This is quite normal, and we had the same experience last year. When the weather improves it’s necessary to wait a few more days for the snow to consolidate before going back up, to reduce the risk of being avalanched by the freshly fallen snow. I understand there has been more snow than usual this year. It’s speculation, but this may have overloaded the ice in the serac fields, creating a greater risk of them breaking off. During those few days of waiting for the snow to consolidate, avalanches are actually a good thing, because they clear the slopes of newly fallen snow, which is the snow most at risk of avalanche.

Some of you may be surprised that expeditions are continuing in the wake of this tragedy, and that it is disrespectful to those who have died. While expeditions do get cancelled after an event like this, it’s unusual, and there are often additional reasons. In 1978 Chris Bonington and his team of elite British climbers famously abandoned an expedition to K2 when their friend Nick Estcourt was killed in an avalanche. They were a close-knit group and some of them lost heart after that, but even so their decision wasn’t unanimous. In 2007 a fatal avalanche on Gasherbrum II in Pakistan led to the mountain being abandoned by all teams. The avalanche had been so huge it had turned a long snow slog into a substantial rock climb, and teams were not equipped for such an undertaking. When I was on Cho Oyu in 2010, the mountain was abandoned by around 400 climbers after two avalanches several days apart. Mercifully all the climbers caught up in them survived, but weather conditions were such that the snow seemed unlikely to consolidate before it was time for teams to head home and back to work.

Personally, if I had been on Manaslu this year, then I think I would have abandoned the expedition, but not because I think it would have been disrespectful to continue. On the contrary, as mountaineers we do what we do in full knowledge of the risks, which we mitigate as best we can. I can’t think of a single climber who would want to see others abandon their expeditions as a result of their own misfortune, and I’m sure the dead would have wanted them to continue. It might sound mystical, but for me there are times when you have a bad feeling about a climb and it doesn’t seem quite right. As with many Himalayan peaks, the Sherpas believe Manaslu is the home of the mountain gods, and it is only with their permission that we climb it safely. Every expedition begins with a puja ceremony to ask for their blessing and safe passage, and the Sherpas won’t set foot on the mountain until it’s been performed. Of course to our secular western minds this seems absurd, but when you’ve spent weeks eating and sleeping on the side of a mountain you give it human characteristics. Failure to reach a summit is part and parcel of mountaineering; sometimes conditions just aren’t right. It seems this year the mountain gods are angry, though I expect there will be summits for those dauntless enough to continue.

How the media report tragedy

While I like to see the sport of mountaineering talked about in the popular press, I think it’s a shame they flock to report it at a time like this. Death sells, but if their audience is not interested in hearing about it at other times, then there’s no need for this mad rush to report the story before enough is known about it. It takes time for the dead to be identified and for loved ones to be informed. In the big scheme of things, there are really not many people on Manaslu at the moment, and the unnecessary reporting of dead climbers’ nationalities will have had many people worried. There are so few people there of any one nationality that effectively somebody is finding out about their loved one’s death through the media. Footage of body bags getting carried out of helicopters will also have been very upsetting. In fact, after two days of silence Russell Brice of the Himex expedition team posted a dispatch which rendered all the highly speculative media stories obsolete. Russell has been coordinating the rescue operation. He took a register of climbers on the mountain, arranged helicopters for evacuation, set up his base camp as a makeshift hospital, sent his Sherpas up the mountain to assist climbers in need, and helped to identify the dead and inform next-of-kin. Only then did he sit down and write about what had happened. He is a source you can trust.

Then of course, there’s the endless quest to apportion blame. Already I have seen the predictable questions about overcrowding on mountains, and the usual snide remarks about commercial climbing. If 30 people camped on a snow slope half a mile high and considerably wider is overcrowding then the whole of Alaska is a slum (one article I read in the Washington Post, now removed, talked quite seriously about there being, and I quote, a crush of mountaineers). Why some of these media organisations don’t close commenting on their websites when reporting a tragedy like this, I do not know. While most mainstream media sites have clear social media policies which state that abusive comments will be removed, I have seen many examples this week of the dead being insulted on websites by insensitive and ignorant people whose comments are left there unmoderated.

Barely 12 hours after the avalanche on Manaslu, a woman was killed by a falling branch as she walked through Kew Gardens in southwest London. There is little Kew can do to prevent such a tragedy occurring again, other than by cutting down all their trees and banning people from walking underneath them. Every second worldwide branches are falling from trees; rarely is anyone killed. The incident at Kew was a tragic accident; there’s no blame attached to anyone. The avalanche on Manaslu is a parallel; it was a freak event. It wasn’t due to recklessness or overcrowding, and every second in the Himalayas bits of ice break off mountains, but rarely is there someone underneath. The only way to prevent it happening again would be to stop people climbing mountains and remove all the snow (something the human race is working on, but that’s another story).

Dedication

I would like to dedicate this post to the friends and family of those who died on Manaslu on Sunday. I’ve been to its upper reaches in a beautiful location above the rhododendron forests of Nepal, and looking out over a line of mountains towards the desert plateaus of Tibet. I know that it’s no consolation now, but maybe in a few years time it will be a comfort to know that when it’s time to lie down, you can do worse than lie above the clouds in one of the most beautiful places on earth.

Related links

- Manaslu 2011 photos and videos

- Spirit Mountain: my attempt on Manaslu (Manaslu background and history)

- Ice axe and Cramptons: the story of Manaslu 2011 (Expedition summary)

- The Manaslu Adventure (Expedition diary)

Good article Mark, thanks for the insight. We also have a feeling here in Canada that Health & Safety warriors (i did not say idiots) supported by cheap media will soon label mountaineering an illegal activity ….. Jarek

Pingback:Manaslu Update: Split Strategies » Explorersweb

Pingback:Manaslu: A Risky Push, a Rescue, and the Days Ahead » Explorersweb

Ten year ago lost my best friend in the 2012 avalanche… Tks for the article it helped me better understand what happened, his body is still on the mountain where he wanted to be if ever this happened

Well written – I know nothing about mountaineering – those guys are with thee families.

Pingback:Manaslu Avalanche: 11 Deaths in 2012 & 3 Deaths in 2022