I thought I was done with the Atlas Mountains when I climbed 4167m Jebel Toubkal, the highest mountain in Morocco, eleven years ago. It wasn’t a terribly exciting climb, and I found the arid desert landscape a bit dull. The villages seemed very austere and my whistlestop visit to Marrakesh, Morocco’s tourist capital, didn’t leave much of an impression.

For one reason or another I ended up booking my Christmas and New Year holiday very late this year, and Morocco became an attractive choice, being cheap and mountainous, with plenty of flights from London. It was serendipity, for everything I disliked about the country was reversed this time around. Unlike Sir Bob Geldof I knew there would be a great deal of snow in the High Atlas over Christmas, and the Toubkal area would be very different from the sweltering dusty desert I experienced in the summer months. The villages clinging to hillsides, with their narrow alleyways and pink mud buildings, seemed to be teeming with life and friendly faces, and with more time to explore the city I loved Marrakesh this time.

I booked my trip to climb Jebel Toubkal and 4089m Ouanoukrim, Morocco’s second highest peak, through the UK operator KE Adventure Travel, whom I’ve travelled with only once previously. As luck would have it they ran it with only two clients, so it seemed almost like a private trip with a good deal more flexibility than we might otherwise have expected.

My companion was Ernie, a retired serviceman in his 60s, who despite a penchant for morris dancing (or perhaps because of it) proved to be an entertaining climbing partner. A talkative character he had an inexhaustible supply of stories from his days as an officer in the Royal Air Force, though nothing ever quite matched his one about the time he served as a juror on a military tribunal for an officer who had been caught pleasuring a farm animal, whose alibi was that it was muddy in the pig sty where he went to relieve himself, causing him to slip and “enter the pig”. Ernie summited Denali, the highest mountain in North America and one of the world’s toughest commercial climbs, only four years ago, so I knew from the start he would be strong and determined.

We started off with a guided tour of Marrakesh, which included 77m high Koutoubia Mosque, the city’s best known landmark, the leafy courtyards of the Palais de la Bahia, and the famous rabbit warren of souks. In this maze of alleyways containing market stalls could be found all manner of colourful souvenirs from spices, slippers, lanterns and tagine pots, to paintings, candlesticks and carpets. Most of these knick-knacks are no possible use once you get them home, but the whole experience of wandering the souks is far more enjoyable if you’re prepared to part with a little cash for entertainment value. In my case this involved an apothecary who could probably have worked in a theatre and would have done very well in panto. He somehow managed to sell me a bottle of argan oil, three bags of mint tea, a dusting of saffron, and a magic black powder which is supposed to be able to cure me of snoring (if it manages to do that I will be returning to Marrakesh to buy a flying carpet). If anyone is interested in any of these items please let me know (preferably in return for something a bit more practical such as whoopee cushion).

South of Marrakesh the snow-capped peaks of the High Atlas were immediately visible from the outskirts of the city, and a short taxi ride took us to Imlil in little more than an hour, the gateway to Toubkal right in the heart of the mountains. What I had previously considered Imlil was in fact a collection of small villages nestling on hillsides at a crossroad of valleys. To the east the road (more of a track when I trekked it in 2003) continued over two passes to the ski resort of Oukaimeden. To the north was Marrakesh, and the southern valley steepened beyond the snow line to Toubkal and Morocco’s highest peaks. To the west was a 2489m pass, the Tizi n’Mzik, which crossed into another valley of villages and provided access to a less frequented climbing region. We walked up to the pass for an acclimatisation hike on our first day in Imlil. Our guide was Omar, a Berber in his mid 20s, who took us to his home in the village of Mzik on the way back, where we were served a few small glasses of mint tea. Anyone who has been to Morocco will know this is a super sweet concoction comprising half sugar and half water with a token sprinkling of tea leaves and fresh mint. It sends many dentists into raptures of joy, and my teeth were already well on the way to becoming marshmallows.

Back at our cold but comfortable guesthouse in Ait Souka that day Ernie started to have equipment problems. He and Omar spent a frustrating evening trying to adjust his Leki trekking poles to a usable length. How Leki remains a leader in the sale of trekking poles is something of a mystery. If I could charge my usual daily rate for the number of hours of my life I’ve spent faffing with the locking mechanism on Leki poles I would have a useful second income. After a good deal of teeth gnashing and brute force (and a commendable absence of profanities) Ernie and Omar eventually tugged the poles into a workable length as long as they never touched the locking mechanism again, but this problem paled compared with the trouble Ernie had with his boots, which although he had worn them many times before, gave him blisters that would have made a Komodo dragon’s skin look as smooth as Patrick Stewart’s shiny pate.

The following day we trekked from 1800m up to Toubkal Refuge, above the snowline at 3200m, in what proved to be a winter wonderland of high peaks. It took us 7 hours in our big mountaineering boots, and we regretted wearing them on the initial part of the trek on a rocky trail up to the tiny pilgrims’ shrine at Sidi Chamharouch. They proved to be useful above this, though. The snowline started at 2300m, immediately above the shrine. The snow was very compact and it was much easier to walk with crampons. I was wearing my new Scarpa Batura boots, which although light as far as mountaineering boots go, proved to be overkill for the High Atlas in winter, and an ordinary pair of rigid walking boots I can attach crampons to would have been quite sufficient.

For the last hour of the ascent we could see the two Toubkal refuges close to the top end of the valley ahead of us, substantial enough to look like a castle nestling high up in an alpine valley. Beyond it two 4000m peaks, Ras n’Ouanoukrim and Akioud, formed a pied wall of black rock laced with snow couloirs at the end of the valley, the second a jagged hump like the back of a Stegosaurus, and the first a smoother skyline lying behind it. Toubkal itself was nowhere in view, though I knew from my previous visit that it lay up a broad gully rising directly above the refuges on the left hand side of the valley. I was in snow heaven for a time, but as we approached the sky clouded over and the sun dropped behind the mountain wall to our right. It was distinctly cold when we arrived at 3.30, but we were immediately ushered into a dining room with a wood fire and treated to a late lunch of salad, rice and eggs. The refuge did not seem too busy, but most of the beds in our 24 bed dormitory were occupied, and as evening approached people gradually emerged from various nooks and crannies, or more likely afternoon walks. By dinner it was very busy and privacy seemed as likely as Slade showing up for dinner to sing Merry Christmas Everybody (so some positives then).

It was a perfect morning when we left for the summit of Toubkal at 7.30am on Christmas Eve. The dry rocky trail that I climbed 11 years ago was now a smooth slope of compacted snow that was a pleasure to climb. Ernie was also finding it easier going than the day before, and although he kept apologising for the slower pace I didn’t mind at all. For someone 20 years my senior walking with blisters his pace was remarkably quick, and it gave me the opportunity to drop back and take plenty of photographs. We crossed two snow plateaus, the first a combe wedged between the west ridge of 3887m Tibheirine and 4030m Toubkal West, and the second a great snow amphitheatre formed by the curving north and south ridges of Toubkal’s main summit. Here we stopped to discuss our options. We had agreed to climb Toubkal West as well if we had time, but the rim of the amphitheatre above us also looked like it would make for a fine ridge walk. In the end Omar was concerned about clouds arriving later in the morning (as well as crowds of people), so we agreed to climb Toubkal first and return via Toubkal West if it was still feasible.

We ascended a slope on the right of the amphitheatre in zigzags, before completing the climb up to the col between Toubkal and Toubkal West on gentler slopes. At the col we stopped to delve into Omar’s bag of trail mix and look down sheer cliffs beyond. We turned left, keeping the cliffs on our right, to ascend easy slopes to the left side of Toubkal’s south ridge. After climbing about 100m we reached a brow and could see Toubkal’s distinctive summit pyramid on a promontory about half a mile away. There was an interesting traverse beneath cliffs to get to it and we stood on the summit at 11am. Although it was bright and sunny there was an annoying vapour thin cloud which obscured much of the view. We had to hurry to take summit photos, as 10 minutes after we arrived the summit was mobbed by hordes of people who had set off after us.

We descended to the col, where Ernie decided to continue his descent while Omar and I went up Toubkal West. It was a steeper traverse than the ascent of Toubkal, with the snow slope to our right dropping away much more precipitously, but it was nowhere difficult, although I had to run to keep up with Omar. We were on the much smaller summit of Toubkal West barely more than 10 minutes after leaving the col, where the clouds had dispersed and we had a much clearer view of the peaks to the west, the twin summits of Ouanoukrim, then lonely Akioud, and the long ridge containing Afella and barely pronounceable Biguinnoussene, which surely has too many letters. All of these peaks are over 4000m.

Omar described to me the route we would be climbing the following day, and it looked a more interesting climb than Toubkal. We were on the summit no longer than 5 minutes, and our descent was rapid with some glissading on Omar’s part (a posh word for something we called sledging at school). Even so we were nearly back at the refuge by the time we caught up with Ernie. We reached it at 1.15, less than six hours after setting out. That evening both Omar and our cook surprised us with a Christmas meal of chicken and chips, and a bottle of red wine. If nothing else KE earned kudos for being the only operator in the refuge that day to provide their clients with booze, but we had also been the only people to climb two of Toubkal’s summits.

Despite polishing off the bottle between us we managed to get away at 7.15 on the morning of the 25th to ascend the top end of the valley above Toubkal Refuge. The climb up Ouanoukrim, Morocco’s second summit, began more gently than the ascent of Toubkal, and for much of the first hour the land rose only gently across a broad, snow-clad valley. Then the track passed between two vertical cliffs no more than 10m apart and emerged into a snow basin. At the far side the land rose steeply and we ascended in zigzags to a 3750m pass, the Tizi n’Ouagane, which we reached around two hours after setting out.

Ouanoukrim now lay to our right and to reach its summits we had to ascend a rocky ridge involving a very short section of easy scrambling. We roped together for this part of the climb, but the rope was more of a hindrance than a help. The scrambling was so straightforward there was little chance of falling, but with about 5m of rope between me and Ernie I needed to keep one eye on my feet and the other on the rope ahead to avoid getting too close and tripping him up with loose coils – an unnecessary complication. Beyond the scramble we needed to climb a 45° snow slope for about 30m. Here the rope might have been useful to hold a fall, but we were all very experienced with axe and crampons, and the slope gave us no difficulty.

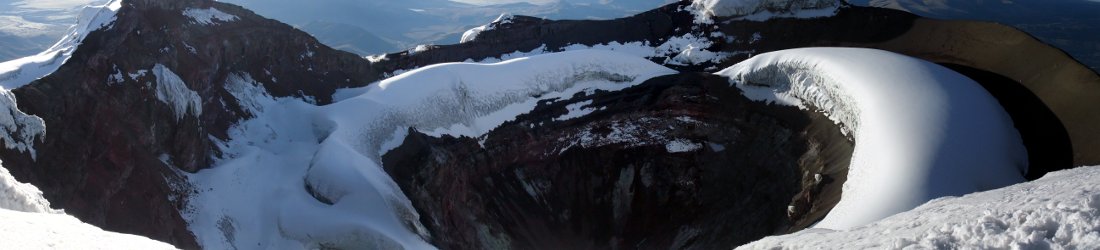

We reached a broad snow plateau beneath Ouanoukrim’s twin summits, and from here it was just a snow plod to reach both. 4083m Ras n’Ouanoukrim lay directly above us, but we chose first to traverse beneath it to a saddle and climb the true summit 4089m Timesguida n’Ouanoukrim, a huge dome of a peak with a summit big enough to play football on. We reached it at 11am, and the view was magnificent. We were now at the southern end of the High Atlas, and beyond us the land dropped away abruptly to the desert plains of southern Morocco. In the middle the Anti Atlas Mountains, Morocco’s most southerly mountain range where I trekked myself way back in 2002, rose from the desert in a 3300m island of snow. The western Atlas peaks were detached from us by a motorable pass, the Tizi n’Test, and to the north we looked across the col to the much more compact summit of Ras n’Ouanoukrim and the plains of Marrakesh dropping away beyond. The view to the east was dominated by Toubkal, but many snow capped peaks could be seen past it all the way to the far horizon.

There was more to come. We left after 10 minutes to climb Ras, but only after I had to return to Timesguida after realising I’d left my ice axe on the summit. We were still roped together at the time, and I felt a bit of a plonker asking the others to turn around. A short distance below the summit we passed another group coming up, and when I saw one of them wearing a Santa hat I suddenly remembered it was Christmas Day. I could think of no better way to spend it than this, among snow-capped peaks with perfect blue skies above.

It took us only another 15 minutes from the col to ascend Ras n’Ouanoukrim. At its lower summit we bumped into a very boisterous Spanish team whom we had been seeing on and off since Imlil. Ernie joined them in an impromptu sing-song which one of them captured on video, but I smiled and politely declined, mainly because I was worried he might produce a pair of handkerchiefs and start morris dancing, and I understandably didn’t want the footage to get onto YouTube with me in it. There was a short gap to cross onto Ras n’Ouanoukrim’s slightly higher main summit. The view was much better here than it had been on Timesguida, with no giant plateau to obscure much of it. The few moments I spent there were the highlight of the week.

It didn’t take long to descend. We avoided the rock scramble by simply whizzing down snow slopes. I was back at Toubkal Refuge at 1.30 some distance ahead of Ernie, who now had serious blisters but was struggling on manfully. He even agreed to continue the descent to Imlil, which turned into something of a death march for him. We left at 3pm, and it took a further 4½ hours to reach our guesthouse in Ait Souka. Darkness descended at 6.15 and we strapped on our headlamps. The Imlil valley was a very different place after dark, and slightly surreal. All the hillsides around us were alive with lights of many villages, and we couldn’t walk for more than a couple of minutes without finding ourselves walking alongside the wall of a building. Yet the setting was also unmistakeably rural as we passed through walnut groves on muddy footpaths with the sound of mountain streams echoing all around us. It dragged on a bit, and I had to keep stopping to wait for Ernie’s boots clomping behind me, but I couldn’t blame him. He never complained and had been an entertaining companion, as had Omar.

I’m glad I returned to Morocco. Winter is definitely the time to visit the High Atlas. It’s cheap and easy from Europe, and now I know the places to visit in Marrakesh. I’m sure I’ll go back there again and climb more of its peaks on picturesque snow slopes.

You can see the rest of my photos from our week in the High Atlas here.

Hi there,

I’m thinking of climbing this range in December as you did but I have little experience of snow climbing and no experience with crampons or an ice axe. I assume that would prevent me getting to any of the three summits? If not could you recommend any experience I should have prior to going in winter and how many ice axes and/or walking sticks I should take? Thanks!

The climbing required on Toubkal and Ouanoukrim in winter isn’t difficult. If you hire a guide and let them know of your experience they should be able to teach you enough while you are out there. Alternatively any beginners’ course on alpine skills will teach you more than enough. One axe and two sticks recommended.

Wonderful report en beautiful photos.

I will be trying both ascends in February with my wife and one of our daughters, so this was a great preview for us.

Thank you!

Wow, looks like you had a great climb. Did you really need these high altitude super warm shoes on your accent?

I did it this year on the first days of March and was fine with salomon hiking shoes. The conditions looked the same as during your climb.

Joseph.