Este artículo también está disponible en español.

I ended my Ecuador diary In the Footsteps of Whymper with the following paragraph:

It’s an enjoyable end to a very successful trip. I know Quito a lot better after today, and I feel sure I will come back to Ecuador some day.

This was no throwaway line. I loved the open geography of Ecuador’s central highlands, a high-altitude landscape of free-standing volcanoes. I’ve remarked before how its mountains provide a good introduction to mountaineering. Many of the peaks are easy day hikes, while the big four glaciated volcanoes of Chimborazo, Cotopaxi, Cayambe and Antisana provide some interesting glacier ascents whose summits can be reached without too much technical difficulty.

The views are magnificent. On a clear day most of the main peaks can be seen from the summit of any other, making it very easy to work out where you are from the relative positions of the volcanoes around you. It’s also a civilised place. You don’t have to rough it too much, and there are some very pleasant haciendas to stay at between hikes.

Here’s a little montage of photos from my last visit to give you a feel for what it’s like.

It took six years for me to fulfil my promise of returning, but over Christmas I will be doing just that.

Last time I was blessed with great weather, and managed to get up five volcanoes: two easy day hikes up Rucu Pichincha (4680m) and Rumiñahui Central (4634m), some modest scrambling up Iliniza Norte (5126m), and the two big ice-capped volcanoes Antisana (5753m) and Cotopaxi (5897m).

This year will be a similar sort of trip, and if all goes well Iliniza Norte will be my only repeat climb. I will be acclimatising with two easy day hikes up Pasochoa (4200m) and Corazón (4788m), and then I hope to climb the two biggies that I didn’t get up on my last visit: Cayambe (5790m) and Chimborazo (6268m or 6310m, depending on who you ask).

Cayambe’s claim to fame is that it’s the highest mountain in the world directly on the line of the Equator, by some margin in fact – only Mount Kenya (5199m) in faraway Africa comes even vaguely close.

It was first climbed – as were many of the high peaks of Ecuador – by the English gentleman-mountaineer Edward Whymper and two Italian professional guides Jean-Antoine and Louis Carrel. Whymper and Jean-Antoine Carrel had an interesting relationship. They were rivals in the race to make the first ascent of the Matterhorn in 1865, a race that Whymper won at a price (four of his party were killed in a fall on the way down).

While on the summit Whymper took gloating to a new level by jumping up and down, whooping, and throwing rocks down at Carrel’s party as they climbed up from the other side and looked up at their rivals doing the Victorian equivalent of high-fiving.

By 1880 this rivalry had been forgiven if not forgotten. Jean-Antoine Carrel was Whymper’s trusted and industrious (if not always loyal) chief of staff during his incredibly successful exploratory expedition to Ecuador. According to Whymper the main purpose of the expedition was to conduct research into high altitude. They did do quite a lot of this, but it was really just an excuse for some very enjoyable peak bagging. In a few short months they were the first people to spend a night on the summit of Cotopaxi, and made the first ascents of Chimborazo, Sincholagua, Antisana, Cayambe, Saraurcu, Cotocachi and Carihuairazo.

Whymper’s Scrambles Amongst the Alps is regarded as one of the classics of alpine literature. I’ve never read it, but the same could not be said of his Travels amongst the Great Andes of the Equator, unless you have a fascination with barometers. Their physics and readings are analysed in great detail throughout. Even the title of the book had me nodding off, but it does have its moments, and it’s an essential read for anyone interested in the mountaineering history of Ecuador.

There was a festival atmosphere when the trio of Europeans arrived at the village of Cayambe on the mountain’s western side. The reason for celebration was a cock fight in progress. Whymper was surprised to learn that cock fighting was still a popular pastime in that part of Ecuador, and even more surprised when the Jefo-politico, or village headman, assured him that “all the best cocks come from England”. It’s a statement which many people in Scotland still believe to be true.

Whymper’s first foray up the mountain came to an ignominious end when he became separated from the rest of his party in thick mist. With no sign of their tracks or voices he retreated down the mountain and spent the night in a thicket of brushwood, before descending through forest to the village the next morning. When he rejoined his party at their 4500m high camp the following day, he was welcomed like a man returned from the dead. A local guide had assured the Carrels that the forest and valleys were alive with pumas and Whymper had surely been eaten.

Their actual ascent of the mountain was much more straightforward. They left their high camp at 4.40am on 4 April. Apart from a short maze of crevasses at the head of an icefall, they found the climb to be a relatively straightforward snow plod. They headed for the middle of three domes, which they judged to be the highest of the three when they studied Cayambe from down below. People in the village could see their figures approaching the summit at 9.30, when clouds descended and obscured the view for the rest of the day.

They reached the summit shortly after 10am.

The true summit of Cayambe is a ridge, running north to south, entirely covered by glacier. Its height (deduced from the mean of two readings of the mercurial barometer at 10.45 and 11am) is 19,186 feet, and this mountain is therefore the fourth in rank of the Great Andes of the Equator. Edward Whymper, Travels amongst the Great Andes of the Equator

In fact Cayambe is the third highest mountain in Ecuador, but Whymper acknowledged that the fourth, Antisana, was very similar in altitude, and he could not be certain which was higher. His reading of 19,186 feet is not far off the 5790m (18,996 feet) Cayambe is now believed to be.

Chimborazo is a little further from the Equator than Cayambe, but in some ways it is an even more remarkable mountain. For a long time it was believed to be the highest mountain in the world, and it still is when measured from the centre of the Earth rather than sea level, due to the rotation of our planet, which elongates its otherwise spherical shape around the Equator. If you don’t believe me then just get out your tape measure and drill a hole to the Earth’s core.

The explorer and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt claimed to have ascended to 19,286 feet (or 5878m) on Chimborazo in 1802, which was considerably higher than anyone was known to have climbed at that very early stage in the history of mountaineering. Like everyone else Whymper accepted this claim without question, until he visited the mountain himself.

When they gained their first sight of Chimborazo on 21 December 1879, Whymper and the Carrels were surprised to discover that it had two summits and was entirely glaciated. Neither Humboldt nor any other accounts of Chimborazo had mentioned these two notable facts. The more Whymper studied the mountain the more confused he became by Humboldt’s descriptions. He failed to recognise any of the features. Most puzzling of all was the following statement by Humboldt.

I have seen nothing in the tropics, neither in Quito, nor in Mexico, resembling Swiss glaciers.

Snow-capped Cotopaxi dominates the view from many locations surrounding Quito, and had Humboldt climbed as high as he claimed on Chimborazo he would have been surrounded by ice.

Whymper and the Carrels made the first ascent of Chimborazo from the southwest on a route very similar, though not identical, to what is now the mountain’s normal route. Their names are writ large across the geography of the area. The approach is up the Valle Carrel. There is a Refugio Carrel at 4856m and a Refugio Whymper at 5043m. The ascent route is known as Ruta Whymper.

Numerous porter desertions and signs of altitude sickness in their mules meant the two Carrels did most of the load carrying up to their high camp at 5268m. Here they opened their supplies to discover an entire crate of provisions had been ruined by an infestation of putrid ox cheek (oxen these days are more polite).

They set off on their first abortive summit attempt at 5.35am on 3 January 1880. They ascended the southwest ridge along a line of rocky outcrops known today as the Agujas de Chamonix. By 7.30 they had reached a series of rocky cliffs they had identified as the crux of the ascent when they studied the route from down below many days earlier.

“Thus far and no further a man may go who is not a mountaineer,” said Whymper in his book.

There was a breach in the rock walls at an angle of 50° which posed no difficulty to their experienced party of three, but at the top they encountered high winds and chose to retreat back to camp.

They set off again at 5.40am on 4 January. With their tracks still in place from the previous day they made good progress, and were above the breach by 8am. The remainder of their route was on snow. They edged around the top end of the Thielmann Glacier, which now forms part of the modern ascent route, and were on the plateau by 11am.

Here things began to get tricky. They didn’t know which of the two summits was the higher, so they made for the closer western one. They encountered snow so deep that at times they were sinking to their necks and could only proceed on all fours. Whymper asked the Carrels if they wished to turn back, but the two Swiss guides were adamant they would continue until Whymper ordered them not to.

The snow became firmer as they approached the first summit, but when they reached it at 3.45 they realised the east summit was higher. With only a few hours of daylight left they were now in a hurry if they wanted to descend back through the tricky breach in the rock walls during daylight.

They waded through similar snow conditions to the second summit, hurriedly completed their scientific observations, and were off again by 5.20. They ran back down their snow trail much more quickly, and were through the breach just as dusk was falling. Luckily their local guides had kept a camp fire burning, which guided them back to their high camp. They returned from the first ascent of Chimborazo at 9pm after more than fifteen hours of climbing.

Over the years various archaeological discoveries have provided evidence of human activity close to more lofty summits in the High Andes. One example is the Llullullaico Maiden, the corpse of a child believed to be a human sacrifice found very close to the summit of 6739m Llullullaico on the Argentina-Chile border. But when Whymper and the Carrels reached the top of Chimborazo, as far as anyone knew it was the highest mountain that had ever been climbed, and remained so until Matthias Zurbriggen reached the summit of Aconcagua in 1897.

Despite the rush, Whymper’s observations were remarkably accurate. He measured the summit of Chimborazo at 20,608 feet (6281m). Even today there doesn’t seem to be any agreement on whether the altitude is 6268m or 6310m. I might take a GPS up there and measure it myself if I get the chance. That should put the record straight.

Whymper wanted to make another ascent to get a second set of observations in more leisurely fashion, but the weather deteriorated, and after sitting out a storm the older Carrel flatly refused to go back up again, perhaps remembering about the Matterhorn.

They eventually returned to Chimborazo a few months later, and made its second ascent from the north side, up the north-north-west ridge, eventually joining their first ascent route close to the head of the Stübel Glacier. This climb was carried out during an eruption on Cotopaxi sixty miles away which coated their scientific instruments in volcanic ash as they took readings on the summit.

The modern route up Chimborazo follows a line slightly clockwise of Whymper’s first one, underneath a rocky spur known as El Castillo. In recent times, as global warming causes Chimborazo’s glaciers to melt, this route has become increasingly threatened by rockfall, so much so that recent success rates by this route have been as low as 30%. It was in particularly bad condition when I went there in 2009/10, and I was persuaded to climb Cotopaxi instead.

A new variation on this route has recently been identified along the Stübel Glacier, which passes beneath the opposite (northern) side of El Castillo. It’s this route that Edita and I will be attempting.

Whatever the outcome, I can’t wait to get back to Ecuador. It’s a country that’s definitely worth a second visit.

I’ll finish with a little home video I shot of my ascent of Cotopaxi with my pal Tony.

If you’re at a loose end over Christmas and yearning to escape to the mountains, then please consider downloading my book Seven Steps from Snowdon to Everest, about my ten-year journey from hill walker to Everest climber. If you enjoyed this blog post then I’m sure you will find it a good read!

Mark, pls get busy climbing and writing your travel diaries. I’ve read them all and your new book, so I need new material from you. Merry Christmas and happy New Years!

I’m glad you enjoyed them. I’m sorry, I wish I could write more quickly 🙂

You did Cotopaxi? Interesting mountain, that one. There is town called Latacunga (pop 100,000) that lies smack in the middle of the lahar path from Cotopaxi. Talk about an invitation to disaster. Ever the obliging mountain, Cotopaxi has buried the town in ash no less than four times but still they build there.

I assume you were up there before the current round of eruptions. Would you go back, given the state of the mountain today?

Cotopaxi was fine when we climbed it. I believe the last eruption had been in 1904. Ecuador’s mountains (or some of them) are still very active and erupt from time to time, but don’t less this stop you from climbing the others.

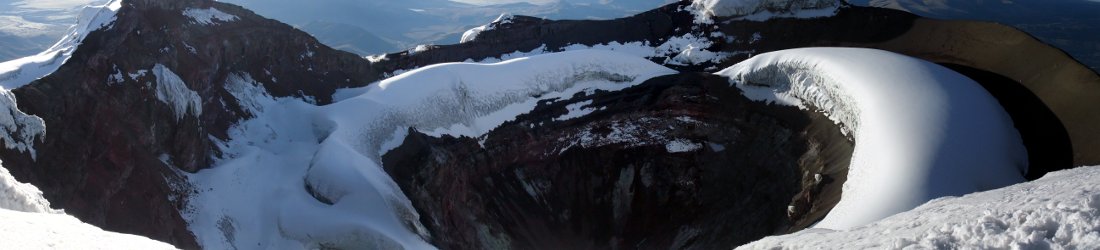

I don’t know whether I will climb Cotopaxi again as there are plenty of other mountains to climb, but it’s definitely worth visiting when it’s safe. The summit crater is very dramatic.

Mark – I’ve been following your blog for some years now and thought it high time I said ‘gidday’, but more particularly thank you for your writings and your ‘Seven Steps…’ publication. As someone who has done a number of treks and ‘climbs’, I have really related to your approach and insights. I’m reading ‘Seven Steps…’ right now and wanted to say thank you for your thoughts and perspectives on not summiting Aconcagua first time round. It struck a chord and we can all learn something here. Good luck with your future adventures and thanks for sharing them with us.

Hi Mark,

I´m Jonas, from de Ministry of Tourism in Ecuador. Can I have a mail to contact you?

I enjoyed reading two of your posts about the mountains of Ecuador. I live in Quito and love being surrounded by mountains. I am planning on climbing Cayambe in January and I would like to know if you recommend any guiding companies in particular. Many thanks, Jura

Hi Jura, we climbed with Andeanface. Very happy to recommend them. My Cayambe trip report is here https://www.markhorrell.com/blog/2016/peak-bagging-on-the-equator/