May 1934, Bareilly Railway Station, India, and two suited Englishman and a Sherpa are running up and down a platform, screaming at the top of their voices, and peering into the carriages of a crowded train, trying to locate two companions they have arranged to meet. Their luggage is packed away inside another train to Kathgodam, due to depart in ten minutes, and their companions are Sherpas who have never travelled on a train in their lives and don’t speak a word of Hindi. Indian railway stations are chaotic places at the best of times, and unless the Englishmen can find the Sherpas and help them, it seems unlikely they will be able to find the connecting train on their own.

But despite their eccentric performance the train pulls away, much to the relief of the passengers squeezed inside, and there is still no sign of the two Sherpas. A whistle sounds, and the Englishmen realise their connecting train is about to depart too. They sprint to another platform and run alongside the train, trying to locate the carriage with their luggage. Suddenly the smaller of the two Englishmen, tugs the shirt sleeve of the other one and points inside one of the carriages. Sitting inside it, comfortably ensconced among the luggage and eating oranges without a care in the world are the two Sherpas.

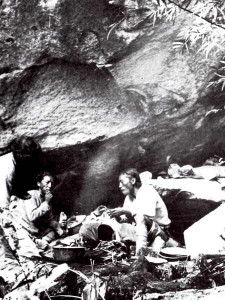

The two Englishmen are the great mountain explorers Eric Shipton and Bill Tilman, and this will not be the first time they come to appreciate the resourcefulness of their Sherpa companions. Over the following five months Shipton, Tilman, Angtharkay, Pasang and Kusang make a thorough exploration of the Garhwal region of India. They become the first people to find a way into the Nanda Devi Sanctuary, a secret haven surrounded by high mountains, cross two watersheds through thick jungle in the rainy monsoon season, at times surviving on a diet of tree mushrooms and bamboo shoots, and return to the Sanctuary to look for a plausible route up Nanda Devi, the highest mountain in the region, believed to be the abode of a goddess. They hire local porters for some of the journey, but often find them unreliable. By contrast the three Sherpas never falter, carrying huge loads over dangerously precipitous terrain. They pitch camp, cook, and help to organise the porter loads, and despite the harsh living conditions, they continue tirelessly without complaint. In fact, Shipton and Tilman find them to be the best possible companions, unfailingly cheerful and possessed of a great sense of humour, always ready to share a joke and laugh at the situations they find themselves in.

Sherpa mob violence?

This is the nostalgic picture of Sherpas that many people share, of a race of genial and hard-working mountain men. It may seem romantic, but it’s a picture many travellers to Nepal, who have spent weeks in the mountains trekking and climbing with Sherpas, take home with them.

But last month that picture changed when three western mountaineers, Ueli Steck from Switzerland, the Italian Simone Moro, and Jon Griffith from the United Kingdom, abandoned their expedition to Everest, returning home with a bizarre story of mob violence at 6400m in the Western Cwm. They were ambushed at Camp 2 by a group of 100 masked Sherpas armed with stones and knives, who threatened to kill them. Simone Moro was dragged from his tent on his knees and made to beg forgiveness, and would have been summarily executed with a rock had another western climber not intervened and saved him. They fled back to Base Camp in terror, and were so scared they had to find an alternative route through the Khumbu Icefall, away from the fixed ropes and ladders put in place for other climbers. For days on end their story was reported in the western media, and journalists and their readers speculated on its cause. How could a people known for their cheerfulness, hard-work and humility have become so violent? The dispute had nothing to do with their own actions, the climbers were reported as saying, but were a result of tensions between westerners and Sherpas that had been building up over twenty years. Everest has become too overcrowded, the media reported, and is now a powder keg. An incident like this was inevitable; the Sherpas are fed up of being mistreated by westerners and were due to rebel. They have a tribal streak, others claimed, and club together in stressful situations.

But hidden behind the sensationalism were alternative versions of the story which went largely unreported. One of the few Sherpas who spoke out was Lakpa, owner of the Nepali mountaineering operator Himalayan Ascent. He said there were many Sherpas and westerners in the Western Cwm that day and not all of them were part of the conflict. Most tried to intervene and calm the situation, but tensions were running high, and when a westerner tussled with a Sherpa violence broke out. According to his account the incident had more in common with a pub brawl than a lynch mob.

With such wildly conflicting stories it’s hard for an objective observer to guess what actually happened. What most people seem to be agreed on was the incident was ignited when the three westerners at the centre of it climbed up the Lhotse Face alongside the Sherpa rope-fixing team, responsible for preparing the route for commercial teams. Because the job of rope-fixing is tough and dangerous, there is an unwritten rule that westerners should not climb the face until it is complete, but because they were climbing unsupported and did not need to use the fixed ropes the three westerners considered themselves to be exempt from the rule. When they crossed the place where the Sherpas were fixing the route in order to reach their camp, the Sherpas objected and angry words were exchanged between their leader and Simone Moro. Later evidence suggests (bizarrely) that Moro may have used the word motherfucker in Nepali while one of the Sherpas was broadcasting to Camp 2 on his radio, and this caused unrest among some of the younger Sherpas listening in.

What’s certain is that an incident occurred in the Western Cwm that should not have happened, an unidentified number of Sherpas used unacceptable levels of violence, and it must have been a frightening experience for the climbers involved. When more eye-witnesses finish their expeditions and return home we will hear more about it, but until then the accounts of the three climbers at the centre of it hold sway. While the real story is likely to be somewhere between the two extremes (like this one), it is their version which has generally been taken to be accurate by the media and readers, and the tendency to sensationalise, provoke hate, make judgements and generalise means the reputation of Sherpas in the west has been damaged unfairly. The violence which happened should be addressed by the Nepali authorities, the Sherpa community, and the teams whose members were involved, but it should not reflect on Sherpas as a whole. Many people who have never been to Nepal, met a Sherpa, or have any historical perspective on their relations with western climbers, have been quick to give their opinion of Sherpas as a race and explain why the altercation happened. One commenter on this blog even appeared to suggest I was defending mob violence by pointing out there were conflicting stories, which is a bit like saying a judge in a murder trial is defending murder by insisting the jury listens to the case for the defence.

This is a post I have been meaning to write for a while, and the incident on Everest last month has given urgency to it. Much has been written by westerners about Sherpas over the last hundred years, but the voice of the Sherpas themselves is rare indeed. I can’t provide it either, but I can provide my own perspective of a people who have given me many happy memories, taken me to places I could never have been without them, and put their lives at risk to help me. I don’t recall a single violent incident, and it saddens me to read some of the things that have been written about them over the last few weeks. If I can do anything to help restore their reputation, I will, and if this account also seems romantic, it is with good reason.

A brief Sherpa mountaineering history

The Solu-Khumbu region of Nepal (popularly know as the Everest region) is the spiritual home of the Sherpas. Originally Tibetans, they probably migrated over the Nangpa La pass and into Nepal in about the 16th century. The name Sherpa means easterner, because they originally came from the Tibetan region of Kham in the east. They were mostly traders who made a secondary living by farming. Unlike Nepalis from the south, they were used to the high desert climate of Tibet and didn’t find the high mountain climate of the Solu-Khumbu at all harsh. To them it was a green paradise. The prevailing Himalayan weather system comes from the Bay of Bengal and deposits rain and snow on the south side of the Himalayan divide, leaving the north Tibetan side dry. The Sherpas made their home in the Khumbu, growing crops on its fertile slopes, and trading salt, wool, grain and cotton with their kinsmen across the Nangpa La in Tibet. By the early 20th century their migratory traders’ lifestyle had taken many of them across the high passes to Darjeeling in northeast India.

It was around this time the British were becoming interested in exploring the Himalayas on the northern fringes of their Indian empire. The first person to discover how well suited the Sherpas were to mountaineering expeditions was a Scottish doctor called Alexander Kellas, who made eight expeditions to the Himalayas, in Garhwal and Sikkim, between 1907 and 1921. He usually travelled on his own, employing just handful of Sherpas from Darjeeling as high altitude porters. His expeditions were over mountainous terrain, across many glaciers and high passes, and his ascent of 7128m Pauhunri in 1911 was the highest mountain that had ever been climbed, but because its height had not been measured accurately nobody realised this fact at the time. He made many studies into the effects of altitude on the human body, and was considered the world’s leading expert on high altitude physiology. Tragically he is best remembered for his death, which occurred during George Mallory’s Everest reconnaissance in 1921, but perhaps he should be remembered for being the first mountaineer to employ a Sherpa.

Following Kellas’s lead, the British launched many expeditions from Darjeeling and found the Sherpas, with their background of living in the high mountains and travelling across them, were ideally suited to employ as porters and mountain guides. While they lacked the technical climbing skills of western mountaineers, they were immensely strong and courageous, and the British discovered with the aid of fixed ropes they were willing and able to carry heavy loads up very difficult terrain. They trusted their employers and cheerfully helped them in their goal of trying to climb the highest mountains without the ambition to summit themselves. While the British took pains to ensure the safety of the Sherpas, mountaineering is a dangerous activity, and it is likely the Sherpas did not realise the risks they were being exposed to.

During the 1922 Everest expedition George Finch and Geoffrey Bruce spent two nights waiting out a storm in their tent at 7800m high on the North Ridge, They were freezing cold and close to exhaustion, and survived by taking it in turns to suck on oxygen from a cylinder. Later in the afternoon there was a break in the weather and at six o’clock, as they were settling in for a second night, they heard voices outside the tent, and six Sherpas appeared bearing flasks of tea. They had climbed 800 metres up a steep snow slope from their camp on the North Col, and immediately headed back down again. The hot tea was like nectar, and the following day Finch and Bruce climbed to 8320m before ending their climb, the highest man had ever been. Next time you order a drink on hotel room service, and a bell boy arrives at your door carrying a tray, remember this story. For the Sherpas that expedition was to end in tragedy. After two unsuccessful assaults on the summit, on the 7th June George Mallory and Howard Somervell set off with 13 Sherpas up the slopes of the North Col Wall for one final attempt before the monsoon arrived and heavy snow made the mountain unclimbable. They never made it. About halfway up they heard a loud explosion above them and looked up to see they were in the path of an avalanche. They were swept down the slope in a wave of snow, swimming frantically to keep themselves above the surface. When they came to rest they were able to pull themselves free, but below them they could see two rope parties of 9 Sherpas had been buried alive. They rushed down and were able to pull two of them free of the snow, but seven died. The Sherpas had trusted the British to lead them safely, but there had been a great deal of fresh snowfall, and Somervell and Mallory knew they had been taking a great risk. Somervell summed up their feelings later.

“Only Sherpas and Bhotias killed – why, oh why could not one of us Britishers have shared their fate? I would gladly at that moment have been lying there dead in the snow, if only to give those fine chaps who had survived the feeling that we shared their loss, as we had indeed shared the risk.”

Howard Somervell, After Everest

The expeditions continued, and there was not one in which the Sherpas didn’t play an integral part. In the 1930s German teams launched a series of disastrous expeditions to Nanga Parbat, an 8000m peak in what is now the Pakistan Karakoram. Although local Balti porters had been used by many expeditions to the Karakoram, Sherpas were still considered much better at high altitude, where technical climbing was required. In 1934 six Sherpas and three German climbers died during an agonising eight day retreat through a storm high on the mountain. One of them, Gaylay, became a legend among the Sherpas by staying with the leader of the German team, Willy Merkl, and dying beside him when he might have escaped. Three years later nine Sherpas and seven German climbers died on the same mountain when a huge avalanche wiped out their camp as they slept.

Slowly the Sherpas were beginning to establish themselves as skilful climbers in their own right, and not just as high altitude work horses. It was the western climbers who had led the way, but the Sherpas were beginning to show more mountaineering wisdom. On K2 in 1939 the German-born American Fritz Wiessner probably owed his life to Pasang Dawa Lama, when the pair of them reach 8400m, just 200m short of the summit. Night was approaching and they would probably have reached the summit before dark, but they might also have become another Mallory and Irvine, disappearing into the clouds, never to be seen again, and no one knowing whether they made it to the top. Wiessner wanted to go on, but Pasang Dawa refused. They turned around and survived, but not without a fight. As they descended to Base Camp they discovered their camps had been inexplicably stripped and taken down by their team mates while they were on their summit push. Another team mate, Dudley Wolfe, had been abandoned sick in a high camp with no one to help him. Wiessner and Pasang Dawa were too exhausted to do so, and it was as much as they could do to get themselves down safely. With the American climbers reluctant to help and keen to return home, it fell to three more Sherpas, Pasang Kikuli, Pasang Kitar and Phinsoo, to return up the mountain to try and rescue him. Neither they nor Dudley Wolfe were ever seen again.

In 1950 a French team made the first ever ascent of an 8000m peak when they climbed 8091m Annapurna in Nepal. With Maurice Herzog and Louis Lachenal at their final assault camp at 7500m was their sirdar Angtharkay. He was the same Angtharkay who had been with Eric Shipton on that station platform in 1934, and was a legend among the Sherpas, with years of experience behind him. Herzog generously acknowledged that if anyone deserved to reach the summit of an 8000m peak the following day then it was Angtharkay, and he invited him to join them on their summit bid.

“Thank you very much, Bara Sahib,” said Angtharkay, “but my feet are beginning to freeze and I prefer to go down to Camp 4.”

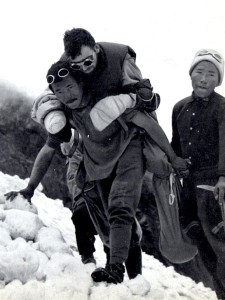

The following day Herzog and Lachenal reached the summit, but they both suffered terrible frostbite and their descent became a nightmare. Both Sherpas and their French team mates came up to help them down to Base Camp, but it fell to Sherpas to carry the pair on their backs through the jungles and rice paddies of Nepal on the retreat to civilisation. Both climbers lost all their toes to frostbite, and Herzog all his fingers too. Herzog became a national hero, and never regretted his decision to reach the summit. Angtharkay’s thoughts were never recorded, but he relied on his feet for his livelihood, and it is likely he had no regrets either.

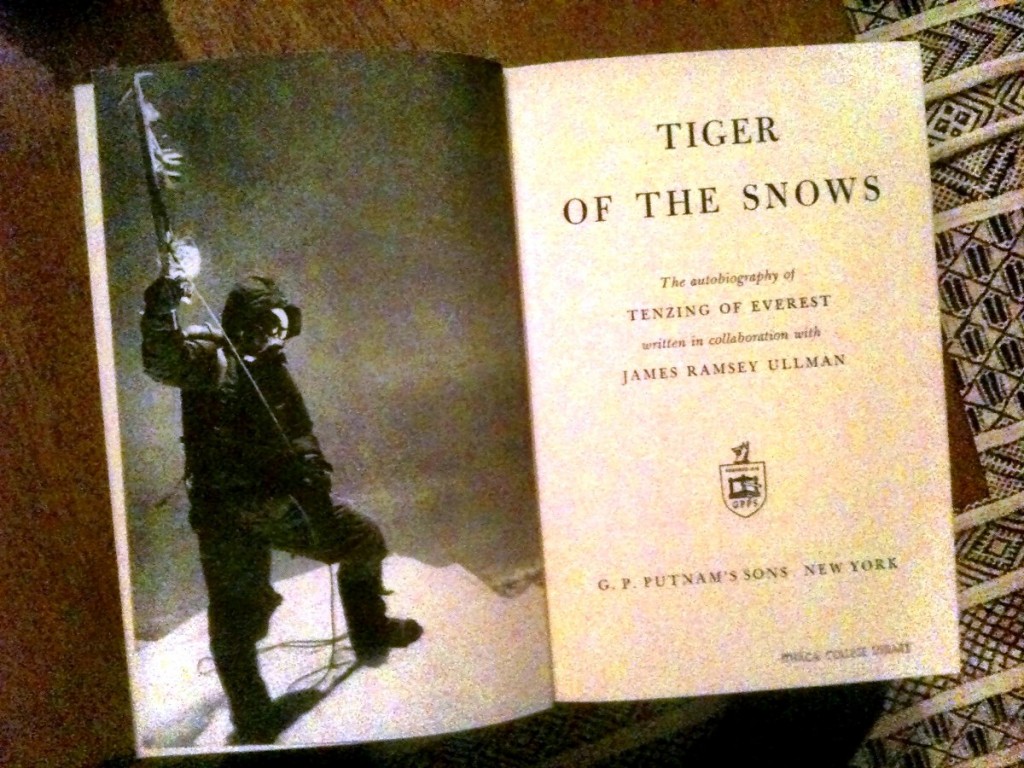

But other Sherpas were setting their sights on the summits, and one in particular was to become the greatest of all Sherpas and arguably the greatest Everest climber. I’ve talked about Tenzing Norgay’s contribution to the history of Himalayan mountaineering in another post quite recently. It’s a post that is very relevant to the subject of this one, and touches on the relationship between Sherpas and western climbers. In it I argue that Tenzing was the greatest Everest climber because he had to work much harder than the others. Not only was he a lead climber, but he was sirdar, and in an echo of the events on Everest this year, the British had him to thank for quelling a mutiny in the ranks in the early part of the expedition. He was one of the first Sherpas to yearn for a summit and between 1935 and 1953, when he reached the summit of Everest with Edmund Hillary, countless western mountaineers had him to thank for his hard work, organisational skills, and ultimately his climbing ability.

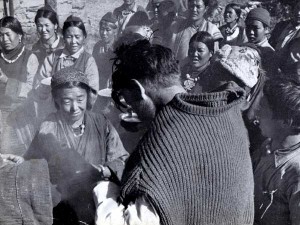

And for those who think the incident on Everest this year springs from tensions between Sherpas and westerners over the last 20 years, they should reflect that this happened 60 years ago. On his return to Kathmandu after reaching the summit Tenzing was swept along by a crowd of eager Nepalis waving flags and banners, and crying, “Tenzing zindabad!” (Long live Tenzing!). Nepalis and Indians alike claimed him as their own, and asked him to sign statements saying he reached the summit before Hillary. The nationalist fervour led to tensions between Tenzing and his British team mates, and there were angry statements in the press on either side. You can look for the roots of a conflict anywhere if you want to, but sometimes the explanation is simpler.

Meanwhile other Sherpas were following in Tenzing’s footsteps to the summits. The following year, 1954, the same Pasang Dawa Lama who had been on K2 with Fritz Wiessner in 1939 joined an Austrian expedition to climb 8201m Cho Oyu. Halfway through the expedition he returned across the Nangpa La to his home in the Sherpa capital of Namche Bazaar to join his family and procure fresh supplies. While there he was promised a wife and substantial dowry if he reached the summit. He hurried back across the Nangpa La, and three days later made the first ascent of another 8000er with Herbert Tichy and Sepp Jochler. Their return to Namche turned into a two week festival and the two Austrians spent most of it drunk at the insistence of their Sherpa hosts, something Tichy later claimed cured him of frostbite.

A personal perspective on Sherpas

Not all Sherpas are elite mountaineers, but there are a remarkable number who are. Many disparaging comments have been written about Sherpa climbing skills over the last few weeks – that they lack the technical ability of the top western climbers. This may be true, but it misses the point. Technical climbing ability is rarely the most important quality in Himalayan mountaineering. The capacity to endure hardship, perform with immense strength at extreme altitudes, and ferry heavy loads over steep terrain, are much more important skills to have on most routes. Here the Sherpas are among the elite; sure, there are western climbers who are just as strong, but they are the exception rather than the norm, and are usually at the top of the pecking order. Sherpas are often the work horses, carrying out their work without complaint and with great dignity, yet they are the Premiership footballers of high altitude mountaineering. They take the greatest risk in preparing the route for western climbers. The icefall doctors are the Sherpas who fix the ropes and ladders over the crevasses of the Khumbu Icefall into the Western Cwm, under constant risk of avalanche and ice collapse. One of them, Mingma Sherpa, died from a fall early in the season, and of the four climbers who have died on Everest so far this year, three have been Sherpas. NSPCC ambassador David Tait was reported as being one of the first to summit on 10 May this year, yet he was following right behind the Sherpa rope fixing team, who arrived first and made the route safe for him and all the other climbers who will summit from the south this year.

I have trekked, climbed and travelled with Sherpas ever since my first visit to Nepal in 2002. Many earn a living as mountain guides, cooks and porters on western treks and expeditions. Most of them like a drink, and I have bought them many. They are always willing to share a joke and see the funny side of life. I am forever in awe of their strength and stamina at high altitude, and their courage over dangerous terrain.

My first encounter with elite climbing Sherpas was on 7546m Muztag Ata in western China in 2007. Three Sherpas were with us there, and all of them had summited Everest that year. There were a couple of occasions when I arrived in a high camp and began to carve out a platform for my tent. It was unbelievably hard work after an exhausting climb at high altitude, and I never got very far before a Sherpa arrived and took over. I rested and let them get on with it, and without their help my climb would have been so much more exhausting. The day after our successful summit, they were packing away our high camp at 6800m and I asked if there was anything I could help them to carry. One of the Sherpas, Gyalzen, looked around for a few seconds before selecting two foam mattresses, which looked very bulky by the time I had tied them to the outside of my pack, but weighed next to nothing. This was typical behaviour for a Sherpa, happy to shoulder the majority of the burden, while allowing his clients to feel good about themselves.

In 2009 I competed a very happy trek in the Khumbu with my friend Mark Dickson, and a crew of fourteen Nepalis, most of whom were Sherpas. We climbed two popular trekking peaks Mera Peak and Island Peak, and crossed a difficult technical pass, the Amphu Labtse, which involved scaling ice walls and abseiling down rock overhangs. We completed the crossing with technical equipment, including crampons, ices axes, carabiners and climbing harnesses, but our Sherpa porters had none of that, happily completing the crossing with heavy loads carried on their foreheads with head straps. I watched nervously from a ledge on the far side as the loads were lowered on ropes down a short vertical section. The Sherpas happily skipped down after, using only an arm wrap on a fixed rope for security. I abseiled down behind them, but got into a spot of bother when I reached the bottom of the rope at an anchor point, and found myself turning upside down. I righted myself and started climbing back up the rock as far as I could, but before I could solve the problem on my own, one of the porters waiting at the bottom, Drukchen, noticed my predicament, ran up the ice slope I was intending to abseil down, tossed me a rope and legged it back down again. When I finally reached the bottom an older porter, Lhakpa, was there to take my arm and guide me to a wider ledge. I didn’t need the help of either man, and in many ways it was embarrassing, but they both considered it their duty to offer assistance to a westerner who found the terrain harder than they did.

On Gasherbrum II in 2009, an 8000m peak in Pakistan, we were the only team on the mountain with Sherpa support. One evening we were lying in our tents at Camp 1 in the Gasherbrum Cwm when a light began flashing on the mountain over 1500m about us. A climber had gone missing close to the summit the previous day and was believed to be dead. Now here he was signalling his distress in the darkness high above. There were many climbers at Camp 1 that day, and within minutes they had gathered outside our tents, even though the climber in trouble was not attached to our party. We were the only team with Sherpas, and everyone knew if a rescue was to be carried out, only Sherpas would be quick enough and strong enough to reach the man and bring him down safely. It is ever the way on the commercial 8000m peaks, and Sherpas have saved many lives. They are true heroes, but often their help is taken for granted, as it was that day on Gasherbrum.

When I embarked on my summit push on the north side of Everest last year, I had twice been up the North Col Wall, and once to the North Col itself at 7060m. But our Sherpas had been all the way to Camp 3 at 8300m, establishing our camps and leaving vital supplies such as oxygen cylinders ready for us as we arrived at the camps on our summit push. Even so, I found it incredibly tough, and my backpack seemed heavy. I would never have managed had our Sherpas not done all that work for us in preparing the way. My summit day took 18 hours, and my personal Sherpa, Chongba, stayed with me throughout, making sure I got back to Camp 3 safely. Another Sherpa, Ang Gelu, gave me a helping hand on the Second Step, when I found myself struggling up a smooth rock. I owe them my success, and perhaps my life. We had a very happy expedition, with a good relationship between Sherpas and westerners. I don’t know what they say about us behind our backs, perhaps they laugh about us, but if so then they disguise it very well. We shared a celebratory drink with them on several occasions during our return to Kathmandu, and personally I believe our friendship was genuine.

When I see some of the things that have been written about Sherpas over the last few weeks by people who have never shared these experiences, it’s difficult to know how to react. Should I laugh or should I be angry? Everest is a powder keg, they say. Sherpas are fed up of being mistreated by foreigners over many years and are ready to rebel if they’re not given more power. They think Everest is their mountain, and are jealous of any climbers who appear to be better than them.

They could be talking about different people in a different world. These descriptions don’t match those of the Sherpas I know.

Even if the statements were accurate, they are almost childishly trivial. Of course Everest is their mountain. Half of it lies in their country, the Khumbu, and if anyone has earned the right to determine what happens there in the future, it is the Sherpas. The ones who climb Everest are highly respected within their community, and earn an income far in excess of what their ancestors who perished in the avalanche in 1922 could ever have dreamed of. But when I shared a glass of Everest beer with our climbing Sherpas in Sam’s Bar, Kathmandu, after our expedition, and asked them whether they hoped their children would follow in their footsteps, they all said no. They wanted to send their children to good schools so they could become educated in a way they themselves hadn’t. They all believed that education was the route to prosperity, and not high altitude mountaineering.

Whether you believe Lakpa Sherpa’s account of the Everest fight last month to be the accurate version or not, his was a rare educated Sherpa voice providing a Sherpa perspective, and he made one statement we should all take to heart.

“As a Nepali owned outfitter, we often hear our western outfitter friends acknowledge that the skilled Sherpa climbers deserve more. But what are they actually willing to give more of? More money? More benefits? More fame? Perhaps they should start with more respect.”

Another rare Sherpa voice is that of Tashi Sherpa, owner of the outdoor clothing manufacturer Sherpa Adventure Gear, who spoke to Ed Douglas in the Guardian shortly after the Everest fight, and had this to say.

“People talk about 10 or 20 years of frustration. I don’t think there’s any frustration. If anything, Sherpas are a lot better treated now than they were 10 years ago. We have a voice. Along with development and education, we have a clearer understanding. It’s no longer that idea of the simple native.”

As Sherpas become better educated and more westernised, it is inevitable they will begin to assert more authority over expeditions to the Himalayas, and rightly so. After all, on Denali in Alaska, the highest mountain in North America, only a handful of American companies are allowed to operate, and foreign operators must all subcontract their services. While this may be taking things too far, I for one will not complain if the Sherpa voice, silent for so long, becomes louder in the coming years.

This has been my longest ever post, and if you have read all the way to the end, thank you sincerely – it means a lot. You probably feel like you have just climbed a huge Himalayan mountain. In true Sherpa style, go and get yourself a beer.

If you want to hear more of the Sherpa voice there isn’t much I can suggest, but all of it is worth reading. Jonathan Neale’s Tigers of the Snow is written by a westerner, but considers things from the Sherpa perspective, concentrating particularly on the Nanga Parbat tragedy of 1934 and the heroic behaviour of Gaylay Sherpa. Jamling Tenzing Norgay’s Touching My Father’s Soul is written by a westernised Sherpa, brought up in Darjeeling but who has lived much of his life in the west. The greatest Sherpa account of all is his famous father’s autobiography Tiger of the Snows, written in collaboration with the American mountain writer James Ramsey Ullman.

And if you can suggest any other Sherpa accounts, please let me know in the comments below. They will jump to the top of my reading list for sure.

[Special request, May 17: Please, no more comments about the fist fight. It’s not what this post is about. Please do feel free to share your experiences and memories of the Sherpas you’ve known and travelled with.]

Did you enjoy this blog post? This post also appears in my book Sherpa Hospitality as a Cure for Frostbite, a collection of the best posts from this blog exploring the evolution of Sherpa mountaineers, from the porters of early expeditions to the superstar climbers of the present day. It’s available from all good e-bookstores and is also available as a paperback. Click on the big green button to find out more.

Did you enjoy this blog post? This post also appears in my book Sherpa Hospitality as a Cure for Frostbite, a collection of the best posts from this blog exploring the evolution of Sherpa mountaineers, from the porters of early expeditions to the superstar climbers of the present day. It’s available from all good e-bookstores and is also available as a paperback. Click on the big green button to find out more.

Hi Mark,

What a lovely post!

I agree that the Sherpas are not given enough credit.

They seem like a lovely hard working people who always put themselves first.

They also seem very generous of heart!

I don’t like reading negative posts abut them, and as one knows, every side has two stories. Thank you for representing them in a positive light!

Lisa Gibson

Thanks, Lisa, glad you agree, and thank you for reading.

Sorry, but I think that characterizing my comment on your last effort as “a bit like saying a judge in a murder trial is defending murder by insisting the jury listens to the case for the defence” is a rather disingenuous misrepresentation. It wasn’t that you pointed out the existence of other accounts, but that you appeared to accept them uncritically – “thankfully the Sherpa perspective is beginning to emerge in more objective accounts”.

As you are casting yourself in the role of judge in the case, you should probably have observed in your summing up that those pieces were written by people who (a) didn’t witness the events described (one was in Colorado!) and (b) have their own agenda: in particular, one depends on the uninterrupted efforts of the Sherpa rope fixers. Also that there are accounts by other witnesses which explicitly (Kellogg) or implicitly (Arnot) more closely corroborate the European climbers’ version of events. Finally, that Moro vehemently denies calling for a f___ing fight at Camp 2 on open radio frequency – that at least should be relatively straightforward to settle as there would be many potential witnesses.

I do agree that it’s a shame not to have eye-witness accounts from the Sherpas, but I was trying to point out why your cited alternatives are no substitute. And I think it’s fine to counterbalance the negative impression of Sherpas generated by this incident with the many instances in which they have behaved peacefully, generously and selflessly.

But I’m afraid that the tenor of your comments did appear to suggest that since the Sherpas you have met were such nice chaps, the violence either can’t have happened, or was justified by provocation. I am glad you’ve clarified that.

When I see footage of England football “fans” on the rampage around some hapless foreign city, I don’t recognize myself or any of the Englishmen I know in that mob, and I think it would be unfair, if understandable, for an observer to take them as typical of English culture and behaviour in general. But I can’t deny that they exist, and that they are created by our society.

[On a side note, whilst you rightly observe that when someone gets in trouble high in the Himalaya it is almost invariably Sherpas who are called on to help them out, two notable exceptions are Moro – who performs hazardous helicopter rescues of Sherpas and Westerners – and Steck, whose attempted rescue of Inaki Ochoa on Annapurna deserves to be called heroic if anything does in the mountains.]

Heehee, thank you Jim, for demonstrating perfectly why I needed to write this post!

Great post, Mark.

I keep reading your posts over and over again as though I will find something new or a different angle to criticise but this post seems pretty straight forward to me and I think when the storm blows over there will be faults to be found on both side. I did say earlier that I wouldn’t say anything about the incident again and this time I mean to keep my word. I really enjoyed the article though. Cheers Kate

Too right, Kate, behave yourself. This post is about Sherpas, not the fist fight. 😉

Hi Mark, I remember many rainy weekends in my parents’ caravan in Derbyshire, reading several of your aforementioned titles 🙂

https://www.markhorrell.com/blog/2011/5-great-books-about-mountain-exploration/

The one which made the greatest impact on me was Tilman’s ‘Seven Mountain Travel Books’. I felt it captured the spirit of adventure and humanity far more succinctly than any of the publications about Everest’s first ascent which followed, despite the latter being a far more significant event. Human endeavour is not about achieving the best, it’s about being our best, in the way we choose to approach life’s challenges.

I’ve now been to Nepal on 5 occasions over the last 25 years and each time I never fail to find both joy and sadness in all I find there. A country with such splendid mountain scenery and culture, yet so much poverty, political instability and unrest. Surely the one factor that sure holds the country together is the indomitable spirit of the people – and not only the Sherpas. This is what keeps me returning to Nepal more than the spectacular mountains, which are surely just as impressive in India or Pakistan.

I recall on my last visit to Nepal, our guide telling us that he had seen another porter keep a man’s wallet that had accidentally fallen on the floor on the night before. He said it worried him because Nepalis never used to do things likes that. Where did they learn this kind of behaviour? It’s certainly not part of their upbringing. The old adage, ‘If you lie down with dogs, you’ll get fleas’, must surely apply.

And sadly, there seems to be even more ‘fleas’ on Everest every year; hopping over each other, sometimes on top of each other, to reach the summit. Whilst many have acquired mountaineering skills, they do not bring the spirit of mountaineering with them. My apologies to those who climb Everest purely for the joy of the mountains, but I firmly believe that they sadly are in the minority, who are more likely to be found climbing smaller, yet equally meritable objectives elsewhere.

Who was responsible for the fisticuffs on Everest? Well personally I don’t care – and neither should any of us. It’s all just ‘noise’ in the grand scheme of things. What’s important is the realization that this situation is the outcome of developed nations exploiting a less developed one for it it’s own (selfish) needs. 100 years ago it was for the natural resources the sub-continent offered – now it’s for the opportunity to climb their mountains.

What just happened is just one more calamity in the comedy of errors that gets replayed on Everest every year. We should all take a leave out of Eleanor Roosevelt’s book… “Great minds discuss ideas. Average minds discuss events. Small minds discuss people.” – and quickly move on.

Matt Smith.

Well said, Matt. Now, anyone here want to talk about Sherpas instead?

A delightful. engaging piece of writing Mark,which I really enjoyed but I thought we weren’t going to mention “it” again. Last time I did I got my hand smacked by you. Cheers Kate

You said it, not me. I’ve been studiously ignoring any attempt to make me mention it again. 🙂

Pingback:Monatsrückblick Mai 2013

Having encountered your posts by chance, I appreciate your profound view on history, and insights into (changing) social circumstances. Most of all: There is no simple “black and white” scheme concerning the relation between asian people and workers and western mountaineers.

Yet there is something to be added.

There are excellent early examples of partnership. You report about Shipton/Tilman and Ang Tharkey in 1934.

More over I’d like to emphasize Herbert Tichy’s adventures with Kitar to Tibet in 1936 and with Pasang Dawa Lama, Ajiba and Gyaltsen crossing Western Nepal in 1953. Even more: it was Pasang’s desire, he urged Tichy to “climb a big mountain” together (Cho Oyu), not Tichy’s idea.

On the other hand there are been early reports about Sherpas’ arrongance in the expedition business: Already in 1935 (Shipton’s Everest Recce), just to show their privileges, the Sherpas (with Ang Tharkey as sirdar) refused to carry any loads (not even their own gear) before they arrived at the real high altitude tasks.

My own experience as a non-commercial trekking and climbing guide since 1988 is: better to avoid Sherpas. I made friends with Tamang und Magar, managing critical situations in snow storms, and being supported on summit bids and forays.

This is just to stress that there might be an over-exaggeration of the Sherpa people compared to the other people in Nepal and Tibet, I early focussed when Reinhold Messner talked about “these splendid Sherpas, and other tribes”.

We should focus upon the country where we are guests, also and all over to real partners, not only users.

Uli

(Germany)

Once I started to read I could not stop, Your type of descriptive writing makes me feel Iam on the mountain. I just got back from Nepal and was there in 2011. I have met a few Sherpas and the one word I think of them is ‘Warm”. Thanks for your insight into the Sherpa.

paul

Hi! It’s very helpful – thank you! You’ve mentioned how Tilman and Shipton find Sherpas jovial so I was wondering if it is possible for you to append bibliography (of sorts) to your articles? Not a proper one but just the authors and their books or memoirs. This would be of great help to students interested in Himalayan/mountaineering studies. Thanks again!

Sure, very good question. You could start with Nepal Himalaya by H.W. Tilman and Nanda Devi by Eric Shipton.

Hi. Great article and very close to my heart. Sherpas are exceptional people – on mountains and off. But they are human. I hear many stories from the Sherpas side and not all western climbers treat them with respect. Violence is never justified but there are rules on mountains – written and unwritten – and they must be adhered to. Being a crack western climber does not exclude you from these rules. Nor does it absolve those Sherpas who attacked them. But for 99.9% of the time the rules work well and Sherpas are as hard-working and dedicated as they ever were. One final point – there are just too many people on Everest full stop. Old Tenzing would be horrified. He loved that mountain – and respected it.