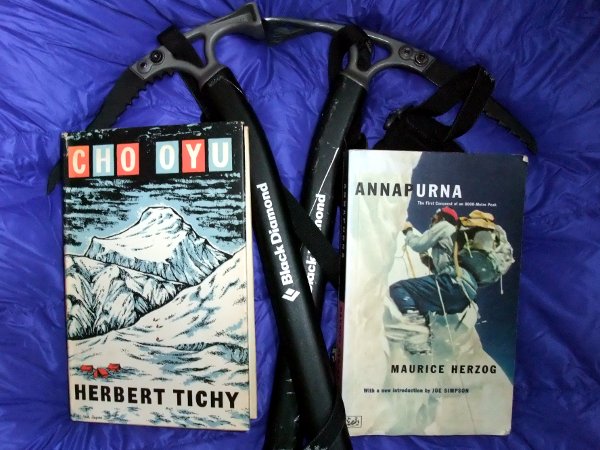

I’ve recently finished reading Cho Oyu: By Favour of the Gods by Herbert Tichy, an account of the first ascent of 8201m Cho Oyu in 1954, and I thoroughly enjoyed it. The book needed to be good, because I paid an eye-watering £130 (around $200 USD) for a first edition English translation. This wasn’t because I’m a book collector with a penchant for rare first editions – I couldn’t care less about that – but because I couldn’t find an English translation anywhere more cheaply. As far as I can tell the translation was only published once and is still in copyright, so there are no digital versions available on archive services like Project Gutenberg or OpenLibrary.

I enjoyed Tichy’s book Himalaya so much that I was keen to read his account of Cho Oyu’s first ascent. Himalaya is Tichy’s memoir of a lifetime’s travel in the Himalayas written in an easygoing style so obviously inspired by a simple love of mountains. He talks about the landscape, the people, Buddhism, the wildlife, and mountaineering history with a reverent awe, and I felt like I was listening to a traveller after my own heart, with no fixed goal but to immerse himself in the places and experiences, enjoy the moment and become enriched by it. I watched second hand book sites for a couple of years hoping for an affordable copy of Cho Oyu to become available somewhere, until I eventually conceded I would need to bite the bullet and stump up the cash. I have no regrets about doing so.

It’s astonishing that such a good book is so inaccessible to non-German speakers, particularly as another account of the first ascent of an 8000m peak, Maurice Herzog’s Annapurna, has been translated into umpteen languages, sold millions of copies and is regarded by many as one of the greatest mountaineering books of all time. In my opinion Tichy’s Cho Oyu is easily as good. The style of writing is very different, but the quality is arguably better. The style of expedition was also very different, but in some ways just as pioneering as Herzog’s. Both books are magnificent stories involving epic struggles and a race against time, and in both cases success was at the expense of frostbite, though with very different consequences.

The more I thought about the similarities between the books, the expeditions, and the two leaders, the more the contrasts stood out even more.

Here are ten contrasts that reveal comparisons are useless. Both books are classics. I wish I could tell you to read both, but the chances are you will only ever have the opportunity to read one. If only some publisher would acquire the rights to the English translation of Cho Oyu and bring it out as a cheap digital version. My first edition copy would instantly become less valuable, but I wouldn’t mind this, as I don’t intend to sell it anyway.

1. The expedition style

By 1950 the race to be the first to climb an 8000m peak had become a national crusade. The British had tried and failed 7 times on Everest, the Germans had a series of disastrous attempts on Nanga Parbat resulting in massive loss of life, various people had tried to climb Kangchenjunga, and the Italians and Americans had multiple tilts at K2.

When Nepal opened its doors to tourism at the end of the 1940s various new routes up 8000m peaks became accessible. It was time for the French to enter the race and prove to the world they were the greatest mountaineers by conquering an 8000er where others had failed.

Maurice Herzog was chosen to lead the expedition by the French Alpine Club, and all the other team members were formally made to swear fealty to him before they set off for Asia. It was a large, well-funded team with six elite climbers, a cameraman, a doctor, a transport officer, and plenty of Sherpa support. It was a major national expedition for the glory of France.

By the time Tichy set off for Cho Oyu four 8000ers – Annapurna, Everest, Nanga Parbat and K2 – had all been “conquered”. The impetus to climb Cho Oyu came not from the Austrian climbing establishment but from Pasang Dawa Lama, Tichy’s Sherpa travelling companion during an exploratory trip through Nepal the previous year, who suggested it as they were sitting around a camp fire at the end of the expedition. As Tichy described:

“It was not just the wish to conquer a high peak that turned our thoughts to Cho Oyu; it was the longing for the boundless peace of evenings such as these.”

In contrast to the team put together by the French Alpine Club, which comprised the cream of French mountaineering, Tichy invited an alpinist Sepp Jochler because he realised he wasn’t the best of climbers himself (he admitted that “in spite of my generally sound health I smoke a lot and drink without reluctance”) and a geographer Helmut Heuberger, because he felt they needed a scientist. That was it as far as western climbers were concerned. Tichy left Pasang to choose a few of his Sherpa friends to support them, though he confessed “a less strictly organised expedition could never have approached a 26,000 ft mountain before” (he was wrong on this point, for that accolade belongs to Maurice Wilson).

2. The reconnaissance

One thing in Tichy’s favour was the route up Cho Oyu’s west ridge from Tibet was fairly well-known as Himalayan peaks go, and believed to be quite straightforward. A British team including the New Zealanders Edmund Hillary and George Lowe had climbed to nearly 7000m in 1952 as far as a wall of seracs. While the obstacle wasn’t insurmountable, expedition leader Eric Shipton was concerned they had strayed into Tibet without permission, and was worried about their permit for the greater prize of Everest the following year being withdrawn. It was a half-hearted attempt, and they fled back across the border knowing the route could go.

By contrast when the French team left for Nepal they weren’t even sure which mountain they would be climbing. They planned to get up an 8000er, but whether it would be Annapurna or Dhaulagiri, which rise up on either side of the Kali Gandaki Valley, was anyone’s guess. Their British maps contained a number of inaccuracies which they corrected as they explored. To begin with they concentrated their efforts on Dhaulagiri, mainly because they could see it and they were having difficulty even finding Annapurna. By the time they decided Dhaulagiri was too difficult, they were yet to find a way to the foot of Annapurna, never mind a practical route to its summit.

3. The mountain

These days Cho Oyu is generally regarded as the easiest 8000m peak to climb, while Annapurna is believed to be the hardest and most dangerous. After their 1952 attempt Shipton suggested the “formidable barrier of ice cliffs” which had ended their attempt would take a well-supported party two weeks to overcome. When Tichy reached its foot one afternoon he intended to set up camp and start their assault the following day, but Pasang was keen to crack on, and he set off up it with the rest of the team in pursuit. Barely an hour later they stood at the top, with Pasang still in the lead. There was one other technical obstacle, a short band of rock, which they encountered on their summit day. By then Tichy’s hands were useless with frostbite, but Pasang was able to haul him up with the rope.

With no previous knowledge of a feasible summit route on Annapurna, Herzog’s team wasted time on the northwest spur, a formidable jagged ridge of ice they named the Cauliflower Ridge because its protruding clusters of ice resembled cauliflowers. After considerable toil Herzog and Lionel Terray looked up it and decided it would take several days to complete, even without the possibility of stumbling across a gap in the ridge they couldn’t see. They opted for an easier but far more dangerous route through the intricate maze of seracs and crevasses of the North Annapurna Glacier. There is no safe passage up this route, where crevasses lurk and avalanches threaten at every turn. These days mountaineers ensure they are pre-acclimatised, and try to pass through it as quickly as they can. The reason they do so is because all Annapurna’s other routes are even more formidable.

4. The leader

Herzog was under no illusion the glory of France was at stake, and nothing else mattered. Even on summit day, when his climbing partner Louis Lachenal realised his feet were becoming frostbitten and asked if they could descend to safeguard his toes, and therefore his career as a mountain guide, Herzog was merciless and insisted they continue.

“Must we give up? No, that would be impossible. My whole being revolted against the idea. I had made up my mind irrevocably. Today we were consecrating an ideal, and no sacrifice was too great.”

His attitude contrasted sharply with that of his more experienced team mates Lachenal, Terray and Gaston Rebuffat. Terray and Rebuffat had no hesitation in abandoning their own summit attempt to rescue their two companions when they returned to high camp helpless. Herzog lost his gloves on the descent and his hands had become severely frostbitten. Rebuffat questioned whether the summit was worth such a price, and later remarked “if only Herzog had lost his flags, instead of his gloves, how happy I would have been!”

I have already touched a little upon Tichy’s character. His reasons for climbing an 8000m peak were different to Herzog’s. His pride and love for the Sherpas shines through every passage of his book, and there is no doubt his delight in the camaraderie of an expedition is as important an end as reaching the summit. He reflects upon this after watching Pasang and Adjiba return from securing the route up the serac wall, and recalls the anxiety he felt for them during a similar moment on their expedition the previous year.

“I almost regretted that we had such an important mission. Success now would not as then be a personal matter; it would mean public recognition and acclaim. That might be why they had been so venturesome. Perhaps they wished for the fame it would bring more than for the experience itself. I felt confused and sad.”

5. The race

After spending weeks trying to climb Dhaulagiri and then find a route to the foot of Annapurna, the French had lost a lot of time, and realised they would be racing to reach the top before the monsoon arrived at the beginning of June, bringing heavy snow that would make the climb impossible, not to mention ever more dangerous. Their speed of progress in establishing camps once a route had been identified was astonishing. They established base camp on 18 May and reached the summit on 3 June.

By contrast the Austrians thought they had plenty of time on Cho Oyu, so much that after being repelled by a storm they sent Pasang back over the Nangpa La to the village of Namche Bazaar in Nepal for fresh supplies, expecting him to be gone for 10 days. While he was away they were horrified to find a Swiss team led by Raymond Lambert arrive at base camp after failing to climb nearby Gauri Sankar. The Swiss had no permit and were keen to join forces for a combined ascent, but this was not what the Austrians wanted at all. Tichy refused and tried to persuade the Swiss to leave, but they made it clear they were determined to climb Cho Oyu.

Pasang was gone, they were running low on supplies, Tichy’s hands were frostbitten, and now the Austrians were in a race against the Swiss to reach the summit first.

6. The star performer

The first ascent of Annapurna was a great team effort involving the cream of French mountaineering. While Herzog and Lachenal may have reached the summit, the contribution of others, including Rebuffat, Terray, sirdar Angtharkay and the team of Sherpas, was significant. Between them they carried loads, established camps, reconnoitred and forged the route up, then saved the lives of the two stricken summiteers on the way down. It would be hard to pull out a star-performer on the French expedition. There was no man-of-the-match.

Not so the first ascent of Cho Oyu. I have talked about Pasang Dawa Lama in a previous post, 10 great Sherpa mountaineers. It was his idea to climb Cho Oyu in the first place; it hadn’t occurred to Tichy before that evening round the camp fire. He is the driving force throughout the expedition, and Tichy makes no attempt to hide the fact. He blazed a route up the serac wall Shipton thought would take two weeks to surmount in barely an hour. After retreating in a storm he was sent back to Namche to get fresh supplies, but in the meantime the arrival of the Swiss at base camp meant his companions had to go back up without waiting for him to return. No matter. He sped back and caught up with them at Camp 4. Then he broke trail and led for the entire summit day. Sepp Jochler, a very talented climber himself, described him as Pasang the Indestructible. On the top he was the most emotional of all of them as his tears soaked the summit.

“He was too happy to speak; he could only sob out over and over again: ‘The peak, Sahib, the peak.'”

The longest chapter of Tichy’s book is the very last one, which is entitled Pasang’s Wedding. It describes a two week party as the conquering hero returns through the Khumbu region, gets married, and is toasted in every village they pass through.

7. The frostbite

Herzog’s book Annapurna is famous as much for the frostbite as for the climb. Lachenal realised his feet were frostbitten before they even reached the summit, yet they continued. On the descent Herzog removed his gloves only to see them slide down the mountain. When he shook hands with Terray back at high camp, the latter was horrified to find he was shaking an icicle.

At Camp 4 on Cho Oyu Tichy’s team woke up in an 80mph hurricane and realised they would have to descend. In their hurry to dismantle the tents Tichy absent-mindedly jumped on one to prevent it blowing away, burying his bare hands in the snow in the process. Instantly they were frostbitten, and back at base camp he asked the doctor from the Swiss team to examine them. The doctor was positive and said if Tichy was lucky he would only lose 1½ fingers. For the time being his hands were useless and he really needed to look after them to prevent further injury, but instead he decided to go straight back up.

8. The aftermath

One of the most memorable scenes in Herzog’s book takes place not on the mountain, but at a railway station in India:

“They opened the door wide and with a sort of old broom made of twigs they pushed everything onto the floor. In the midst of a whole heap of rubbish rolled an amazing number of toes of all sizes which were swept onto the platform before the startled eyes of the natives.”

While waiting in the station the team doctor Jacques Oudot conducted a series of amputations on both Herzog and Lachenal. Long before this he subjected them to a series of painful Novocaine injections to save their hands and feet. These were agonising, and both patients screamed aloud for hours as their team mates held them tight and tried to calm them. With their limbs safe from gangrene, Oudot began the amputations. To begin with he trimmed the dead skin away with a pair of scissors, but eventually he began chopping the digits off one by one.

Then there was the retreat. After returning from the summit Herzog and Lachenal could barely walk, and camp by camp Sherpas came up to assist them as they descended. Herzog and two of the Sherpas were caught in an avalanche and swept 150m down the mountain, but miraculously they all survived and were able to continue. The ordeal wasn’t over when they reached base camp. Porters were recruited to carry the pair back to civilisation on piggy back, often across precarious log bridges.

Tichy also needed help descending Cho Oyu from one of the Sherpas.

“Gyalsen was a pace behind me. Nobody had told him to keep an eye on me, but he clung to me like a shadow … If I stumbled he was there to hold me up; yet if I looked round while I was going well he did not appear to know I was there but looked straight past me.”

Many climbers since have had this experience with Sherpas who have supported them on summit day; I know I have. What made Tichy unusual was that he was happy to acknowledge it.

Once they left base camp the aftermath of the Austrian expedition was very different from the French one. Instead of agonising injections and an interminable retreat through jungle and paddy fields on the back of porters, Tichy had a two week Sherpa party in honour of Pasang, spending much of it drunk.

9. The consequences

Herzog ended up losing all his fingers and all his toes, but he believed reaching the summit of Annapurna was a triumph for the French nation to be proud of. Despite his terrible injuries he described it as “a treasure on which we should live the rest of our days”. He became Mayor of Chamonix, Mayor of Marseille, and French Minister for Sport. Throughout his life he was a French national hero, and died in 2012 at the age of 93. He never once regretted the loss of his digits.

The consequences for Tichy were very different and I described them in more detail in a previous post, Sherpa hospitality as a cure for frostbite. He made a complete recovery from his frostbite, and didn’t lose so much as a single fingertip because, as my post describes, the Sherpas of the Khumbu provided their very own miracle cure which I can heartily recommend to anyone, whether or not they have frostbite. Tichy didn’t go on to become mayor of anywhere or minister for anything, but I would like to think his general outlook led him to live a much more fulfilling life. Another great Austrian mountaineer Kurt Diemberger certainly thought so. He dedicated a short chapter of his book Summits and Secrets to Tichy and said of him:

“Herbert would never climb a mountain-face as an end in itself. This wanderer over the earth’s surface says he is no climber; but that did not prevent his strolling up to above 26,000 feet, through tempest and icy cold, towards the wide Himalayan sky, even to the white dome of Cho Oyu.”

He was still travelling the world well into his 70s before he died in 1987 at the age of 75. I think he would have been a great man to share a drink with.

10. The book

I can only repeat what I said at the start. While Annapurna has sold over 11 million copies, has been translated into dozens of languages, and is regarded as a mountaineering classic, I suspect Cho Oyu has been read by very few people outside Austria. The mind boggles. It deserves a far wider audience.

Herzog ended his book with a memorable closing line There are other Annapurnas in the lives of men. Tichy closed Cho Oyu with a final paragraph equally profound. They had made many friends on the expedition, but had not grown to know their porters particularly well. Just as they were leaving from the aerodrome in Lukla one of them, an elderly Sherpani, burst into tears at their imminent departure.

“When I look back to Cho Oyu today, to the mountain which engrossed so many weeks of our lives and will be an inseparable part of all our days to come; which we sometimes loved and sometimes hated; which we feared and yet made our own, I always see its peak through this veil of tears. They seem to me to be the real success of our expedition, worth more than the peak itself.”

I hope some day someone will perform a great service by translating Tichy’s many other travel books into English.

Thanks a lot Mark! You just cost me $150.

Haha, a pittance for the World’s Top Motorcycle Dealer. $50 less than my copy, so you’ve snapped up a bargain. Glad you’ve decided to buy it – you won’t regret it!

Awesome post!

Thank you for another great post, Mark! Sounds like a great book, and it is very nice to hear that a big mountain was first climbed in a sane, healthy manner (as opposed to Herzog’s Annapurna).

Are they considered classics because they were the first books to bring the experience to the readers?

Mark, I’ve read all your books and I would put your books as equal or even better than these two.

That’s very kind of you to say so, Ruben, but my travel diaries are not in the same league by any stretch of the imagination.

Both of these books document historic first ascents which ended up being epic adventures, and both were written by expedition leaders who knew how to write a good story.

By contrast my e-books are simply what I scribble in my tent every evening, with only a light edit and no regard to plot construction. But that’s OK, because I give them away at only $1 a shot, and I understand people enjoy reading them. So for that, thank you, but they should not be compared to these two great mountaineering classics.

I’m currently working on my first proper book about my adventures, which will be much better than my diaries.

Hi Mark, I have read Annapurna and like you enjoyed it immensely. But the best mountaineering book I have read is Walter Bonatti’s Mountains of my life. He has another one the title of which I cannot remember right now, but like yours it costs around £100 for it as it is so hard to get hold of. One I am really enjoying right now is Reinhold Messners book about his ascent of Everest without oxygen. Off on a slight tangent is South by Shackleton and Captain Scotts diaries. Both of those are free on Kindle but you have to search around as the paid ones come up first. With Scott’s diaries, you know when you pick it up that it is not going to end well! But I was so immersed in it, when it got to the end i actually cried, not something that usually happens when you read a book! Also Ranulph Feinnes trips to the poles are well worth a read. Hope you are well, I love all you books too and am anticipating the big one! take care Bev x

Pingback:Amazon Herzog Annapurna | Smiling Experts

I was fortunate enough to find Cho Oyu on inter library lone. The horrid thing is that it had been checked out 5 times in the past 21 years.

Hi Mark,

I found Tichy’s Cho Oyu in the library of the Italian Alpine Club, but as in Italy by law 50 years older books can’t be borrowed, I only could but browse it.

And due to the cost I decided not to buy it…..

But eventually I found it in PDF!!! and free!!!

Here is the address to download it:

http://pahar.in/wpfb-file/1957-cho-oyu-by-favour-of-the-gods-by-tichy-s-pdf/

Wow – what an extraordinary website.

Marco Fedele, what an incredible link to the PDF….can’t wait to read it. The photos are so heart-warming, and astonishing. These are some of the most evocative photos I’ve seen of the Himalaya climbing experience. The text seems written with a lot of heart, in contrast with the bloviating “Annapurna” by Herzog. “Annapurna” is much more colonial in its response to the Sherpas, and indeed the whole experience of travel at that time. It was actually painful to read at times, Herzog’s view of the Sherpas and his team mates, and even the country. Different people, Tichy and Herzog, I suppose. I’ve recently read that Louis Laschenel’s side of the story finally came out in the 2000s at some point, and Herzog does not come off well in that account.

Marco Fedele, I had a chance to read Tichy’s book, via the link you provided. What a find! And thanks Mark for leading me toward it with this great article. What warmth and kindness, spirit and love for both the Himalaya and especially the people of the Himalaya, and his team-mates—both his Austrian teammates and the Sherpas! What a snapshot of an incredible time in history.

It brought me to tears many times. So poetic, so well-translated, and so action-packed. What heart! They climbed to reach a goal, yes, to be first to summit; and Cho Oyu is no comparison to the challenge of Annapurna, but Tichy climbed for the love of the mountains, for the love of climbing, for the love of their climbing companions. There’s no comparison between Herzog’s account of his climb, which struck me as totally ego-driven, goal-oriented, squash whomever you need to on your way up and down, which is fine for whoever likes to climb like that, but don’t expect me to love the account or the writer. How emotionally cold is Herzog’s Annapurna in comparison.

How strange this book is so little known. Wikipedia has almost nothing on Tichy, and does not even mention the book at this time (April 2017).

People, if you’re even a little curious, you *must* read this book!

Marco Fedele found it in PDF, and free. I’m reposting the link.

http://pahar.in/wpfb-file/1957-cho-oyu-by-favour-of-the-gods-by-tichy-s-pdf/

Thanks for the pdf link. I read Annapurna for the first time in 1970, and re-read at least parts of it every 10 years or so. I look forward to reading Cho Oyu as well.