As the Nepal earthquake starts to slip down the international news agenda my Facebook timeline remains jam-packed with stories from people helping out as the aftershocks rumble on and aid continues to be distributed. In the first few weeks after the initial 7.8-magnitude quake many of these posts were from western tourists caught up in the tragedy, who stayed out there to help out, raise money and distribute aid. I take my hat off these people, even if there were times when some of these posts seemed a little self-indulgent. More than a month on most of these have petered out, and what remains are posts by people who live in Nepal, be they westerners or Nepalese, for whom daily tremors have become a part of their lives.

Apparently earthquakes are easier to predict these days, a fact that’s maybe not that helpful, and some experts are saying the Nepalese should brace themselves for another big one at any moment. It’s difficult to imagine living a life where every loud noise and minor shake has you ready to leap up and run to a place of safety, and where everything you’ve acquired over the years may come crashing down around you at any moment.

On the other hand, difficult times make you stronger and it’s amazing what people can put up with when they have no choice. In a country where the average income is $700 per year, the government is inherently corrupt and does very little to look after its citizens, and the landscape so mountainous that what roads there are have to be rebuilt every year when summer rains sweep them away in landslides, it would be easy to curl up in a ball and feel sorry for yourself. If two major earthquakes and 250 tremors in a month were not enough, on Saturday Kathmandu was engulfed in a dust storm, and later that evening a huge landslide in western Nepal dammed a major tributary of the Ganges, causing water levels to rise by 200m and form a new lake, and producing the potential for a catastrophic flood.

By contrast we have it much easier here in the UK. On Friday there was a 4.2-magnitude earthquake a few miles away off the Kent coast. It was one of the biggest earthquakes we’ve had in a long time, and I must have slept through it. I don’t know how shaking is officially measured, but they say the 25 April earthquake in Nepal was 260,000 times more powerful. On a comparative scale this means if it felt like a bomb going off in Kathmandu, then in Kent things were a little bit wobbly. As for our government, while most of us have political preferences, in Britain we can all be reasonably confident basic public services will continue to run smoothly whoever we vote for. While our system is far from perfect, the serious acts of corruption our politicians have committed include claiming expenses to build a home for pet ducks.

Opportunities to be resourceful exist in both countries, and what the earthquake proved to me – if I needed it – is that the Nepalese are among the most resourceful people I know. One of the best examples I’ve seen of this in the last few weeks is the Himalayan Climate Initiative’s Resilient Homes initiative, a portable earthquake-proof house that can be carried to mountainous areas on porter back.

Nepal lies on a junction of two major tectonic plates, the Indian Plate, which is gradually moving north underneath the much larger Eurasian Plate, a movement that has been happening for thousands of years, causing the Himalayas to rise up at the plate boundary. I’m no expert in geology, so any scientists reading this will have to forgive me if the following explanation sounds a bit facile, but as I understand it the earthquake that occurred in April was the tectonic equivalent of constipation. The plates needed to go badly, but they were not able to complete their movement, and were left in a state of unstable discomfort, ready to erupt at any moment. This has led to aftershocks which will continue until the necessary relief has been obtained.

While landslides caused a lot of damage, the most widely-reported being the serac collapse at Everest Base Camp which killed 19 people, as is the case with most earthquakes, collapsing buildings posed the principal danger to human life. Despite the known threat, very few buildings in Nepal are earthquake-proof, and in remote villages almost none of them are. Clearly one of the most tangible means of support we can provide for people living there is to build them new homes that are able to withstand a major tremor. But how much does it cost to build an earthquake-proof house in a mountainous area which cannot be reached by road?

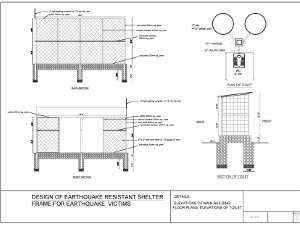

Not very much, according to the Himalayan Climate Initiative (HCI), a not-for-profit cooperative of a dozen or so Nepali businessmen working to provide the country with sustainable resilience to climate change. In the days following the first earthquake they created a prototype home which can be carried to remote mountain areas in 20 porter loads and assembled on site by villagers. The prototype is principally a steel frame and corrugated iron roof which is easily assembled, leaving the villagers to build the walls around it from local materials, be they bamboo, other wood or stone. One was erected after the first 7.8-magnitude quake in a village which suffered extensive damage after the second 7.3-magnitude tremor. Representatives from HCI returned to the village afterwards to find that while other buildings had collapsed, the prototype remained standing.

The plans for the building are open source, and have been posted online on their Facebook page so that other agencies can make their own houses, and engineers can examine the plans line-by-line and contribute improvements. Budget updates are posted regularly, and the cost fluctuates as the price of materials and labour change and plans are adjusted, but it seems to be hovering around the $1200 mark. If you’re thinking of making a generous donation to Nepal earthquake relief, you could therefore do worse than buy someone a house.

Here in this short video is Everest summiteer and mountaineering operator Dawa Steven Sherpa explaining a little more about them.

HCI is one of the local partner organisations of CHANCE, the UK-registered Nepal education charity I am a trustee of. Among their many areas of work HCI operate Nepal’s national volunteering database. Our charity is National Award Operator for the Duke of Edinburgh’s International Award, a scheme that encourages young people to take up activities outside the school curriculum, including volunteering. HCI will be using The Award as means of encouraging volunteering over a longer period of time.

State-funded schools in Nepal closed down immediately after the first earthquake. Many school buildings were destroyed and others have been declared unsafe, which means when schools reopen many of them will be without a safe place to teach. There is an urgent need to provide temporary shelters, and CHANCE has released £30,000 from our funds to seed a £100,000 appeal to tackle various aspects of education, including safe shelters, in the aftermath of the earthquake. HCI’s earthquake-proof prototype is intended for residential housing, but a classroom-size version would provide a cheap long-term solution for a large number of schools.

I’ve said it before in this blog and I’m going to repeat it. Life in Nepal can’t be easy at the moment, but it’s not all bad news. Those who live difficult lives have a much greater capacity to get back up again after taking a fall. The Nepalese have achieved a lot through private enterprise with very little support from government, and this tendency has been magnified in the aftermath of the earthquake, with volunteers working together to rebuild the country.

As Dawa Steven Sherpa says in the video, people in Nepal will rebuild their homes and get on with their lives whether we help them or not. The country has great natural resources, but one of its greatest assets is its people, and that (along with its mountains, of course) is one of the main reasons I keep returning there.

If you are interested in making a donation to support the Himalayan Climate Initiative’s many programmes to tackle climate issues in Nepal, details of how to do so can be found on their website. If you are interested in supporting CHANCE’s programme to tackle education in Nepal after the earthquake you can do so via our Earthquake Appeal page.