I was tapping away on my keyboard last Thursday when a friend reminded me that one of Britain’s premier rock climbers was doing a lecture at the Royal Geographical Society in London that evening. Rock climbing isn’t generally my thing unless there’s a fixed rope to haul myself up on, but this particular lecture had an Everest theme, as it was being sponsored by the Himalayan Trust, the charity Sir Edmund Hillary set up to build schools and hospitals in the Khumbu region of Nepal, and one of the aims of the evening was to raise money for the families of the Sherpas who died in the 18 April avalanche in the Khumbu Icefall. Leo Houlding had flown in from a climbing trip to Colorado especially to give the talk. So this week I’m going to be making a rare foray into the world of big wall rock climbing, an activity that frankly terrifies me, and not any less so after hearing this lecture.

We probably weren’t Leo’s usual audience of young and thrusting hardcore rock climbing enthusiasts, being mostly older friends of Nepal. Apart from Leo himself (who turned up dressed in a pair of knee length shorts) I appeared to be one of the youngest people there, and it was far from being the sell out you might expect for such a high profile and charismatic speaker. He started by asking how many people in the audience were rock climbers, and whether we understood terms like E5 and off width. A few hands went up, but I expect he concluded he would need to talk in plain English.

He talked about two of his most heavily publicised climbs, both of which were made into films. In 2007 he travelled to the north side of Everest with the American climber Conrad Anker as part of the team making the film The Wildest Dream about George Mallory and Sandy Irvine’s disappearance in 1924. They wanted to find out whether it was possible for the pair to have free climbed the Second Step, and the idea was the more experienced Conrad would play Mallory with the younger Leo playing the climbing greenhorn Irvine. It was a nice idea in theory, but it had a basic flaw in that before he went to Everest the only climbing Irvine had done was a spot of pootling in Spitsbergen. By contrast, although Leo was a newcomer to extreme altitude in 2007 he was already one of the world’s leading rock climbers and was capable of dancing up the Second Step in the style of a tango. He started his presentation by showing us the official trailer for the film, which very conveniently happens to be available on YouTube, so here it is.

“I love the quote at the end of that film,” said Leo. “There’s no dream that mustn’t be dared. That’s from Mallory’s diary, and it’s a quote I’ll be coming back to later.” And so he did, though personally I think it’s a bit of a silly quote.

Conrad and Leo were also hoping to summit Everest using the same equipment and clothing Mallory and Irvine used in 1924, and Leo showed us various photos of them in outlandish period costume. He explained their layering system. There were seven layers in total, with a silk and merino wool base layer (which he pointed out people have since returned to), Shetland wool somewhere in between, and an outer layer of gabardine made by the posh clothing manufacturer Burberry, making them possibly the only two living mountaineers to have ever worn that particular brand.

The film was shot in the giant IMAX format, which meant they had 75kg of camera equipment to lug to the summit with them, consisting of a 25kg camera, 25kg of batteries, and a 25kg tripod to steady it all. Everything was going well until they were struck by a storm on the North Ridge. The cameramen were fine wrapped up in their nice warm down suits and mitts, but Leo and Conrad weren’t doing quite so well in their Burberry trench coats and leather boots. They returned to advanced base camp shivering with cold and close to being frostbitten, where Leo plunged his hands and feet into hot water to defrost.

“Sod that. I wasn’t going to lose fingers for the film,” Leo told us.

Everyone agreed that the specially designed period clothing was all very nice in the 1920s, but it wasn’t worth two elite climbers risking their careers just to prove a point, and from then on they wore modern clothing just like everyone else. They did have better luck when they reached the Second Step, the most difficult feature during Mallory and Irvine’s summit day on the Northeast Ridge. Leo showed us a photo of people climbing it, and explained that it’s 90 feet high but the only really difficult bit is the last 15 feet of sheer rock (which is all very well for Leo to say, but I struggled to get my leg over a large sloping slab towards the bottom when I climbed it). Although Mallory’s team mate Noel Odell swore he saw them climbing a feature on the ridge that in all probability was either the Second Step or higher Third Step (see my post about it) many people believe it would not have been possible for them to have climbed it using 1920s techniques or equipment. All climbers since 1975 have overcome this section using an aluminium ladder left there by a Chinese expedition, so Leo’s team untied the ladder while they had a go at free climbing a crack on the left hand side of it.

“I would rate it as HVS,” said Leo, “or Hard Very Severe,” (which he presumably said for the benefit of any gynaecologists in the audience who thought it stood for High Vaginal Swab). “I’ve done most of Mallory’s climbs in the Alps, and most of them were HVS too, so he was definitely capable of climbing it, but it’s a different story at that altitude. Do I think Mallory climbed the Second Step? I would say it’s extremely unlikely. I didn’t want to be the person to say it on the film, but that’s what I believe simply because of those last 15 feet.”

Interestingly one technique they did have in the 1920s that Leo didn’t talk about was one seldom used these days: standing on your partner’s shoulders. This was how the Chinese team who made the first accepted ascent via the North Ridge in 1960 overcame the Second Step (I wrote a post about that too). One of the photos Leo showed us, of Conrad Anker standing at the bottom of the final section, demonstrates that it might have been possible by this method, since Irvine was quite a big chap.

The second part of Leo’s talk covered a far bolder and more innovative climb, his first ascent of the northeast ridge of Ulvetanna last year, an enormous piece of rock in Queen Maud Land, Antarctica whose name translates in Norwegian as The Wolf’s Tooth. This ascent was also made into a film called The Last Great Climb, a strange title given that it almost certainly isn’t (or indeed, wasn’t). Again he started by showing us the trailer for the film, and again I’ve managed to dredge it off YouTube.

As you can see, it’s quite a scary rock climb and I was in danger of soiling my underpants just watching the trailer, which given I was sitting on the balcony and there were people below me would not have been cool. Leo helpfully explained that the face whose ridge they climbed was 1500m high, which is the height of five Shard buildings. He even showed us a photo of the mountain with five images of the Shard superimposed one on top of each other. IMHO, life would be so much simpler if everyone measured heights of mountains in Shards and it would save a good deal of mental effort converting altitudes into feet for the benefit of any Americans.

After being dropped off in the frozen Antarctic wastes by a giant Ilyushin cargo aircraft, the team set up their base camp on the plateau a short distance from the ridge they intended climbing. Within days of arriving they received a spot of bad news when they heard over the radio that a cyclone was on the way and 80 knot winds could be expected. This was some way off the top end of the Beaufort Scale and could be expected to uproot trees if there were any to hand (which, of course, there weren’t). The team responded in the only way they could under the circumstances: build a few snow walls around their tents, pile into the sturdiest looking one and take down all the others. Happily the hurricane ended up missing them, or their expedition could have been over more quickly than this year’s Everest season.

Leo explained they had three priorities for the expedition: (1) to not die, and to return with all their fingers and toes, (2) to complete the route, and (3) to make a good film of the climb. He said that (2) and (3) were of equal priority. Their first few days of climbing appeared to be quite enjoyable, if you’re into that sort of thing (I have to confess I would rather spend a month’s holiday indoors watching TV programmes about cookery than indulge in that sort of extreme vertical rock climbing). They raced up a slanting 45 degree ridge of rock just a metre wide which they christened the Dinosaur’s Spine and established a camp in portaledge tents emblazoned with the logos of their principal sponsors Berghaus just beneath the main vertical section of the climb. Leo explained that they were having to climb every section twice in order to film and take photographs of climbers who appeared to be leading a difficult pitch.

They were making good progress when suddenly the weather turned bad. He showed us footage of him edging painfully up a harder section with the wind whistling across him. His hands were gloveless and he explained that he was being filmed in temperatures of -20°C. The previous day they had been climbing in -5°C, which was on the edge of sensible for gloveless hands. -20°C meant certain frostbite, and it also meant a change of tactics. Instead of free climbing with bare hands and rock shoes (using technical equipment for safety only, and not to assist with climbing) they would have to don big mitts and plastic boots and resort to aid climbing.

They descended to their ledge in a storm and realised they had just six days left to complete the ascent and descend again before the aircraft was due to come and pick them up. This realisation helped to focus the mind, and thereafter they made good progress up the ridge, although they were now doing it in cold weather and poor visibility. The glossy magazine photographs were over, but now they had footage of epic climbing in stormy conditions. Their summit video could have been shot on top of any Scottish mountain, but for what had gone before, the rack of climbing hardware they wore, and the joy and relief on their faces. Leo shot the video as he asked each of the other three summiteers how they were feeling on that great occasion.

“Manly,” one of them exclaimed.

Then he swung the camera around to reveal their cameraman and film maker Alastair Lee had actually made it to the summit with them.

Leo’s talk had a poignant postscript. One of the summiteers, Sean ‘Stanley’ Leary died in a BASE jumping accident two months ago and his wife was due to give birth that very day. Although they had fulfilled their number one priority of returning home safely, this sad ending did highlight the stark reality that those who indulge in climbing and extreme sports at such an elite level have an alarmingly high mortality rate. The flip side is they are all supermen, and I am in awe of what they did.

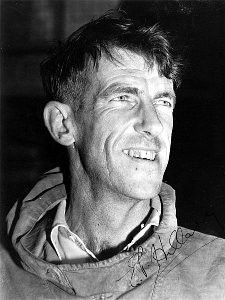

Which led onto the final part of the evening, and its main purpose, the fundraising. Master of ceremonies Rebecca Stephens, who was the first British woman to climb Everest in 1993 and is now Chairman of the Himalayan Trust UK, showed us a film of the late Sir Edmund Hillary and his friend and Everest team mate George Lowe, who died last year, visiting schools in the Khumbu region of Nepal which have been built and funded by the charity.

“Hillary, Hillary” the kids were chanting as they arrived.

“It’s not the mountains but the people who keep us coming back here,” George Lowe said to his friend as they walked along a trail.

He is not alone in that feeling. Hundreds of trekkers and climbers visit the Everest region every year. They return home retaining a huge amount of goodwill for the Sherpas who have helped them to achieve their dreams, and they resolve to help out by donating to charities like the Himalayan Trust.

Rebecca then introduced us to Ang Jangbu Sherpa, an inspirational figure who attended one of Sir Edmund Hillary’s schools as a child but dreamed of becoming a helicopter pilot. While working in the trekking industry as a young man he was lucky to have caught the attention of a wealthy trekker who took him under his wing and sponsored him to visit the United States and train to be a pilot. He graduated with flying colours (literally) and is now a commercial airline pilot who flies Boeing 747s.

He shuffled onto the stage and quietly explained that he’s not used to public speaking in front of so many people but agreed to talk because the 18 April avalanche in the Khumbu Icefall left many families back home bereaved and deprived of their main bread winner. He explained that Sherpas in the Khumbu region are familiar with death in climbing accidents, and while they knew such events couldn’t be prevented on Everest, after the avalanche the Sherpas got together and demanded better insurance cover so that families of the victims could be provided for. He explained that they were not striking for better wages, but for greater security.

While this may be true, it occurred to me that I was perhaps the only person in the audience who had lost some of my goodwill for the Sherpas following the avalanche and its aftermath instead of gained it, having observed Sherpa militancy first hand. I was invited to the lecture by a friend of mine Angus, who has recently become a trustee of the Himalayan Trust UK. As a trustee of a charity operating in Nepal myself I was intrigued how he came to be involved in such a prestigious one as this, and had a chat with him about it before the lecture. Outside the entrance they were selling tickets for a raffle for the victims’ families. Angus appeared to be embarrassed when I put my hand in my pocket and produced a fiver.

“No, honestly Mark, don’t feel you have to donate. You’ve spent enough already,” he said.

Angus was right in a way: I invested the best part of $20,000 in the Khumbu region this year to pay for my expedition to Lhotse which was cut short by the Sherpa strike, but another £5 wasn’t going to break the bank if it goes to someone who needs it more than me. I admitted that when people have asked me which of the many charities raising funds for the avalanche victims they should donate to, I have directed them to the Himalayan Trust because of their long history of building schools and hospitals for the Sherpas. You can ensure that money you donate to them will be spent wisely.

But I believe it’s also important to put things in perspective. Since the avalanche Sherpas have been presented as an exploited underclass who have been treated poorly by uncaring westerners in pursuit of Everest glory. This is a grotesque distortion of the true picture by people who are unaware of Sherpa history, and how closely their increasing prosperity over the last hundred years has been inextricably linked to mountaineering expeditions. The Sherpas of this generation may be Everest guides, but their children are the doctors, teachers and airline pilots of tomorrow. Much of this is due to the schools and hospitals organisations like the Himalayan Trust have built, and because of the generosity of westerners such as the one who paid for Ang Jangbu’s flying lessons, but most of all it is because of income generated by the tourism industry. The trekking industry has grown out of the mountaineering expeditions that first visited Nepal. Many Sherpas are now tea house owners or have their own trekking and climbing agencies. Climbing Sherpas are paid comparatively generous salaries which enable them to send their children to good schools.

Organisations like the Himalayan Trust, and the Sherpa community themselves, should be wary of the militant tendency that emerged this year and hope that it doesn’t spread into trekking and other parts of the tourist industry. If this happens then in future it’s likely I won’t be the only person in the audience watching the romantic and heart-warming speeches with one eyebrow raised. However small the problem may be now, there is certainly a new generation of Sherpas emerging who are in danger of eroding the goodwill and generosity of westerners who care about Nepal by being more combative (for example, I saw one Sherpa complain on his Facebook page that he didn’t receive his summit bonus this year). In many ways the direction of movement is positive. You could say the Himalayan Trust are building schools for people who are rapidly taking control of their own destiny, and the most successful charities are those who become obsolete because the people they support are no longer dependent. But this greater control needs to be used constructively. Ang Jangbu didn’t of course mention the Sherpas who threatened to break the legs of other Sherpas if they didn’t go on strike.

Another important point to raise is that a disproportionate amount of charity goes to the Khumbu region and Sherpas who are comparatively wealthy beside people in other parts of Nepal. A great deal, in excess of $700,000, has been raised for Sherpa families already, as I highlighted in a previous post. Many newspaper and magazine reports have described how dangerous the work of a climbing Sherpa is compared with other jobs, but 16 deaths this year in a freak act of nature does not even remotely compare to the 400 Nepalis who have been reported to have died in Qatar building stadiums for the 2022 World Cup. Climbing Sherpas can earn as much as $5000 in the two month period they work on Everest. This may not sound much to westerners living in an expensive city like London, but it goes a long way in a country where the gross national income per capita is believed to be around $700. Most Nepalis don’t have the option of becoming climbing Sherpas. Thousands travel to the Middle East to work in the construction industry and send money back to their families. There are plenty of horror stories and the Qatar World Cup is merely the most high profile one; many are tricked into going by loan sharks who ask them for an extortionate sum to fly out to the Gulf with the promise of a high salary when they arrive. They are effectively sold into slavery, and often their families never hear from them again.

Climbing Sherpas have to contend with some risk, as indeed do all Everest climbers, but they earn a good wage for their country and many of their children have much greater opportunities. I would certainly encourage you to donate to organisations like the Himalayan Trust which support the Sherpas. I owe a great many happy memories to them. Having watched the avalanche come down with my own eyes as I made my way into the Icefall that morning, and then seen the bodies air lifted out on long lines, I can’t help thinking about the sacrifice those innocent people made and the great void left behind for their friends and family. But please do also consider donating to charities such as the one I myself am a trustee of, CHANCE, which provides educational opportunities in less developed parts of Nepal (I’m still taking donations on the MyDonate page for my Lhotse climb).

Anyway I’m conscious that, like the puja for the dead at Everest Base Camp this year that was hijacked by militant Sherpas and turned into a political rally, I’ve hijacked this post about a lecture by Leo Houlding in support of the Himalayan Trust, and turned it into a rant of my own. It remains for me to tell you about the raffle. There were some great prizes, including a print signed by not only Sir Edmund Hillary but Tenzing Norgay as well (how on earth they managed this when he died in 1986 heaven only knows), a book signed by Sir Edmund Hillary, and a DVD signed by Leo Houlding.

“It’s a bit crap compared with the other prizes,” Leo said with an embarrassed chuckle as this was read out.

I would happily have won Leo’s DVD, but whatever, it had been an enjoyable and successful evening, well worth the price of my entrance fee and raffle tickets.

Did you enjoy this blog post? This post also appears in my book Sherpa Hospitality as a Cure for Frostbite, a collection of the best posts from this blog exploring the evolution of Sherpa mountaineers, from the porters of early expeditions to the superstar climbers of the present day. It’s available from all good e-bookstores and is also available as a paperback. Click on the big green button to find out more.

Did you enjoy this blog post? This post also appears in my book Sherpa Hospitality as a Cure for Frostbite, a collection of the best posts from this blog exploring the evolution of Sherpa mountaineers, from the porters of early expeditions to the superstar climbers of the present day. It’s available from all good e-bookstores and is also available as a paperback. Click on the big green button to find out more.

Hi Mark, thanks for writing another great article. I’ll refrain from using the words ‘post’ or ‘blog’ because I think that devalues the time, effort and research you clearly put in.

Whilst it’s great that Leo Houlding is doing his bit to help the Sherpas affected by the tradgedy, the whole ‘Everest in tweeds’ theme seems very familiar. Didn’t Ed Viesturs and friend do something identical a few years ago? And they also concluded (after a very short time in similar attire) that they didn’t want to lose their most important digits due to the extreme conditions! I recall that they also removed the ladder to free climb the 2nd step as well, before knocking off the summit in the latest hi-tech clothing.

I don’t suppose we will ever know if Mallory & Irvine made it to the top, but what we do know is that they never made it back. It’s clear that the equipment and clothing at the time was woefully inadequate for the undertaking, even if they did have the technical ability to succeed. I believe that the intrigue surrounding them exists because of the mystery and if we ever found out the truth, one way or the other, it would probably be lost – just like the Turin Shroud.

It’s great that Leo has done something positive for a worthy course, but I feel that this kind of stunt just adds to the media circus that already surrounds the big one. ‘Let’s think of another interesting angle from which we can climb Everest – and maybe get some sponsorship’. What next? Climbing scientists looking for evidence of extra-terrestrial life from a meteorite, that oh, coincidentally landed just below the summit of Everest. Let’s organise a climbing expedition there immediately, all in the name of science of course!

It’s pie in the sky, but the best thing that could happen to Everest would be the construction of an Eiger-style railway, built through the mountain to the summit. The cost wouldn’t be as huge as you might imagine due to the labour costs in Nepal and it would keep Nepali’s employed for years. Tourists would flock to Nepal, not in their thousands, but in their millions for the experience. Climbers would still be able to make a traditional ascent to the summit with the added bonus of easy descent, if they so wished 😀

It all makes perfect sense! Just writing a postcard to the Nepali government…

Matt.

Heehee, thanks Matt, you must remind me the name of that Australian wine you drink. 😉

You mean the Turin Shroud’s not real?

I too am sceptical that the Mallory & Irvine story will ever be “solved” (if that word applies.

The best that could be done is eliminating a number of possibilities and what’s left the best indication.

I was interested to read Leo Houlding’s impressions on the Mallory & Irvine route, especially the 2nd step dynamics.

I’ve no opinion on that myself, but one is reminded of the many and disparate impressions of the severity of the last 15 feet up the crux section, that said Leo’s impressions are most welcome on this matter.

Related to this topic, last year I wrote up a scenario that I devised some years ago that could potentially explain the Odell sighting of Mallory and Irvine’s ‘alacrity’ up the presumed 2nd step crux.

http://www.everest1953.co.uk/sighting-by-odell.html

In summary, it questions the context and the assumption that Odell saw Mallory & Irvine “beginning” the 2nd step attempt when he observed the parting clouds and then perhaps surprisingly climbing rapidly up the step “blind”.

Instead I suggest that in truth we really have no evidence that this 12.50pm sighting was when Mallory and Irvine initially arrived at the step and then just proceeded to climb it “blind”.

Alternatively, I propose it could be argued that what if the Englishmen arrived at the step before Odell saw them at 12.50pm?.

That while still obscured, the pair took some time to study the step and perhaps Mallory alone or even helped to an extent by Irvine, in their own time, climbed the step and managed to affix a rope to a number of identified and usable boulders above the step and then like the “Chinese ladder” once affixed and tested, Mallory descended the fixed rope to fetch the oxygen and Irvine, so that after a rest they then proceeded to climb the step with their oxygen, but now aided by the fixed rope installed earlier and so by 12.50, Odell did see the pair climbing up the step and their “alacrity” is explained by this “pre-installed” fixed rope which acted like the ladder since 1975, aiding their ascent.

The theory may nicely explain Odell’s surprising observation just by questioning the “context” of the assumptions implicit in the sighting.

All a lot of fun to write, but I’m still open minded about the matter still and it wouldn’t surprise me that in their haste and en route to the 2nd step one above the 1st step, they could see the likely route up the 2nd step on the approach and so by the time they reached its base they already had worked out a plan to climb it “blind” and just proceeded up the route regardless as time was of the essence by near 1.00pm and little time for dilly dallying.

That’s for airing this Leo Houlding account Mark.

Watch out for falling rocks,

Philip

Quote: “All climbers since 1975 have overcome this section using an aluminium ladder left there by a Chinese expedition”

Please note that the first free-climb of the Second Step already occurred in 1985 by Catalan climber Oscar Cadiach, who free-climbed the pitch on lead under monsoon conditions, using a sling tied around one of the Chinese ladder’s rungs as a runner. He rated the 15-feet crux UIAA V+, which is just about British HVS or USA 5.8. The hevy monsoon snow, not existant during Mallory & Irvine’s attempt, might have shortenend the crux somewhat, but the downside was that the pitch was capped by a cornice, which Cadiach had to cut through with his ice-axe. Cadiach’s report is available in Spanish at http://www.sge.org/sge07/07/oscar_cadiach.asp

Thanks, Jochen, interesting stuff. I hadn’t heard the story before. And a night at 8600m as well. There’s lots of Himalayan history we miss out on because it’s never been translated into English. Thanks for pointing it out.

Incidentally, it looks like the page has moved, but I managed to find the new location. Here’s a shortlink to the Google translated version, a little hard to follow at times but I could just about make sense of it.

http://hoz.me.uk/1jApHyx

Further to Jochen’s point, interested readers may find it edifying to consult his website

http://www.jochenhemmleb.com/german/mundi/index.php

Indeed from section 4.3, there is useful details about the other known free climbs of the 2nd step in the public arena ranging from Oscar Cadiach in 1985, Theo Fritsche in 2001, Nickolay Totmjanin in 2003 and Conrad Anker/Leo Houlding in 2007.

Leo Houlding has described his latest thinking this year, but in summary Cadiach rated the crux headwall as ULAA V+ (5.7-5.8), Fritsche about IV+ and V- (5.6) with the last moves in the V+ (5.7-5.8) range, Anker 5.8 – 5.10 (V+-VI+) and now Leo Houlding describes his 2014 thinking above.

This is useful information, but speaking for myself now, I would argue that these assessments are just vignettes in a much longer story for Mallory and Irvine toward the summit.

Specifically, what if they had of climbed up the 1st step not via the open gully of the right flank of the 1st step which is taken by most people, but in that unknown environment for the first time, they opted for surety in the gloomy mists and adhered to the ridge crest, leading to the ascent up the frontal “snout” of the 1st step (past the later Chinese Camp VII upper) and then climbed up the top “dome” of the 1st step to its apex.

If they went that way (hypothetically), then that too is a nasty climb and seldom done these days.

My point being if they went this way and suceeded in climbing the upper dome of the 1st step that way (with a lot of vertical climbing), then by the time the 2nd step was reached, they may well have thought it to be just another similar climb that they had already negotiated lower on the 1st step.

Indeed, the 2nd step may even be less difficult than the frontal upper dome of the 1st step?.

Context is important where I suggest its important not to fixate on the 2nd step.

In conclusion, what if Mallory & Irvine actually found the 2nd step less of a bother than the 1st step earlier?.

I tend to analyse their total climb rather than a subset of the 2nd step.