The self-fulfilling prophecy is … a false definition of the situation evoking a new behavior which makes the original false conception come true … the prophet will cite the actual course of events as proof that he was right from the very beginning. Robert K. Merton, The Self Fulfilling Prophecy

The other day I was copied into the following conversation on Twitter, which raised an old chestnut:

I don’t know whether these ladies were being entirely serious (they had read my book, after all), but their reaction was a common false assumption that people make in response to media hype about Everest — that inexperienced people pay a lot of money to try and climb it, therefore it must be easy to climb if you can afford it.

They were reacting to an article in the Daily Telegraph about crowds of inexperienced people on Everest. The article was largely accurate — it’s true that more people try to climb Everest each year, and the competence of the least experienced appears to be diminishing — but it wasn’t reporting anything new.

The mistaken belief that climbing Everest has now become a piece of piss has been around for a few years now. When I returned from my own ascent of Everest five years ago, I was so incensed by the media hyperbole that I wrote a blog post entitled 5 media myths about Everest busted, that was shared widely and is still my all-time most-read post.

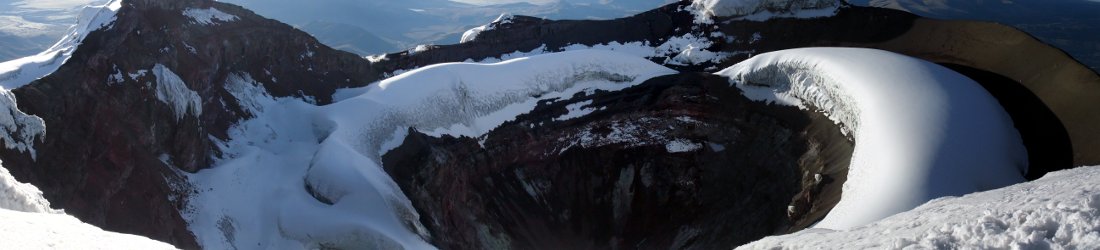

The very first myth I addressed was that climbing Everest is easy. I pointed out that in the course of a six-day summit push, I lost my appetite and hardly ate. My summit day lasted eighteen hours, I drank no more than a litre of fluid. My mouth was so dry by the end that I felt like I was going to retch up a small piece of my throat. I was not only at the end of my tether physically, I was mentally exhausted after an eighteen-hour rock scramble which demanded concentration for almost every step. I saw people who had collapsed and died of exhaustion, and others who had fallen. Death stalked me for most of the ascent. Throughout the climb I was terrified that a single misplaced step could send me tumbling down the North Face into a rock graveyard that had claimed George Mallory and many others.

When you’ve had experiences like these, the idea that it’s possible to climb Everest with no experience and very little effort is laughable.

As we shall see, it is also dangerous. A handful of people die climbing Everest every year. The majority of these deaths are preventable; some are a result of inexperience. The mountain should never be underestimated, even by the most experienced climbers.

Alex, who copied me into the conversation, actually edited my book Seven Steps from Snowdon to Everest, about my ten-year journey to climb Everest, so he knew better.

In the book, I describe this reaction as a self-fulfilling prophecy. People show up at Everest Base Camp, believing they can climb the mountain with no experience. They get reported in the media, along with the false conclusion that it must therefore be easy to climb Everest. People read these articles and believe them. More novices show up the following year without doing their research. They get reported in the media, and so on, ad infinitum.

The inexperienced climbers were not the root cause of this fallacy, but they have now become a contributing factor in this circle of ignorance. Everest is the highest mountain in the world, so it’s always going to appeal to people’s spirit of adventure. The trouble is that there continues to be minimal regulation, either of climbers or operators. You can obtain a permit to climb Everest if you pay $11,000 to Nepal’s Ministry of Tourism. You don’t need anything else; you don’t have to demonstrate any previous qualifications. Similarly, you don’t need a license to be an operator. There are no rules about health and safety, no minimum standards, or requirement to hire experienced staff, and pay them a good wage. It doesn’t matter how many of your previous clients have been killed.

It doesn’t take a genius to see that as long as this situation persists, the trend will continue. More and more climbers with less and less experience will arrive every year. There is no shortage of unscrupulous operators ready to prey on gullible clients. Regulation is badly needed. I blogged some suggestions three years ago; there has been virtually no progress despite major tragedies.

But of course, just because the wrong people are climbing Everest doesn’t make it any easier to climb — any more than the fact that you can catch a train up Snowdon means that you can ascend the Pyg Track by sitting on your backside. Even the man who crawled up on his hands and knees, pushing a brussels sprout with his nose, did some practice first.

In Seven Steps I cited the example of a brain surgeon who wrote to me asking if I thought he could climb Everest with no previous experience. If he was a brain surgeon, then he must have been a clever chap, but even he had been taken in by the hype. I wrote back to him and asked if he thought I could carry out brain surgery without any medical training.

Last week I was reminded by a respected mountaineering statistician that 245 people reached the summit of Everest on 19 May 2012. I was one of them, and it’s a record number of successful ascents for a single day on Everest.

“Hopefully this will stay a world record for eternity,” he added.

It almost certainly won’t, but I can understand his disappointment with these numbers. It will never be easy, but Everest is certainly getting easier as techniques, technology and experience grow. The mountain gods appear to have assisted too — this year climbers are confirming what we suspected last year, that the Hillary Step has now collapsed.

It’s certainly true that in global terms climbing Everest is no longer as special as it used to be. But it will always be special for everyone who stands on its summit. It remains the single most remarkable experience of my own life, something I wouldn’t swap for anything else. Every year, people who have served their apprenticeship, made sacrifices, and summoned up the strength and determination to succeed when their moment came, achieve their dreams on the world’s highest mountain. These are the people who should be serving as an example to others, not the ones who attempted it too soon.

If you are reading this as an armchair observer then give Everest some respect. Ask questions of the media hype, and remember the hardest hill you ever climbed. Think of a slightly harder hill and go and climb that one. Don’t pretend to know Everest until you’ve been up many more and gone beyond what you thought were your limits.

And if you are thinking of following the dream and climbing Everest yourself then take your time. Enjoy the whole experience by climbing as many mountains as you can along the way. Climb at high altitude, to 6000, 7000, then 8000m. If you can, follow the seven steps that I did, when the time comes, you will be ready. You will make the right choices, and you will help to dispel the self-fulfilling prophecy.

Always enjoy your thoughtful posts, Mark.

Regarding the Hillary Step, the Guardian has reported that Nepalese climbers reported, on Tuesday 23 May 2017 13.35 BST, that the Hillary Step is intact:

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/may/23/mount-everests-hillary-step-is-still-there-say-nepalese-climbers

It will be interesting to see how this story unfolds and how it effects the Everest climbs.

Thank-you for your books, and reports from the heights of the world.

The grim reaper is proving your point this season.

Here here. You must have loved Andy Kirkpatricks diatribe of bullshit earlier this season. Made me want to throw up things I had long forgotten eating. I could almost hear you banging your head against the wall from here 🙂

I don’t think I read that one. I enjoy Andy Kirkpatrick’s writing. He has strong opinions that I don’t always share, but he also has a sense of humour that I can sometimes relate to.

I would never think of climbing a mountain. I enjoy your writing and even more so because it is about something of which I am blissfully ignorant. And plan to remain that way except through what I glean from your books.

I don’t really understand why more regulation is needed to climb. The dangers are known and the difficulty is not hidden. For people who seek true adventure where the outcome is uncertain let them have at it.

I don’t mean to be sarcastic about or make light of death but there is no requirement to go climbing and if you choose the risk the the reward is yours alone. Why burden governments in already impoverished countries with looking out for whimsical adventurers with more money than sense?

Wow. Blissful ignorance, indeed. But you’re not ignorant of life, I assume, so here are some analogies.

Why does Everest need regulation? For the same reason any dangerous activity and product needs regulation when it becomes widespread.

The dangers of drugs are well known. People die from drug abuse every day. People know the risks; they choose to take them. That’s their choice; it’s not our problem. Why not just make all drugs legal?

If you’ve followed and understood this post, then you will see that people don’t always know the risks, or they turn a blind eye to them. They believe what they read – that it’s not that dangerous, after all. These people need protecting from themselves. So do the inexperienced Sherpas, lured by the promise of money, and hired to help inexperienced climbers.

The dangers of driving are also well known. People die in road accidents every day. They know the risks, so why do we need traffic regulation?

Because there is a community of drivers. People who do not follow the rules are a danger, not only to themselves, but to other road users. People risk their lives saving others on Everest every year. You rarely hear these stories, but they are common. If a climber is in danger then word comes over the radio, and teams pull together to help, upsetting their plans and putting themselves in danger. The busier the mountain, the more inexperienced the climbers, the worse this situation becomes. Rules are needed to prevent a greater loss of life.

It’s not OK to suggest that because it is happening in a developing country then it’s their problem, their choice, and we shouldn’t worry about it. Everest is a shared resource, shared by people of many different nationalities.

It’s westerners who made it so with their desire to climb impossible peaks. But now it is an important part of Nepal’s economy. Its government makes over $2 million per year in permit fees on Everest alone. Outfitters are hired, hundreds of guides, thousands of porters are paid every year. Food is bought to feed hundreds of climbers for two months. People spend money in teahouses. Trekkers come to view Base Camp and Everest from Kala Pattar.

Impoverished? Far from it. There is wealth to provide a better system. Everyone needs to work together to solve these problems.

I’m so glad I found your blog! I am just shy of 29 right now and have been hiking/climbing/snowboarding for as long as I can remember…I set my sights on Everest a long long time ago, but I’m a single mom and my plans had to be pushed back some lol! My hope is to be able to summit in 2023…everyone I tell this dream to thinks I’m crazy but I really think if I keep on the pace of ramping up to it, I can do it!! It makes me really upset to have to defend my dream every time I talk about it because inexperienced people have this misconception that Everest should be their crown jewel of accomplishments. I feel like the mountain is so objectified….Westerners don’t even see her for what she is.

I sure hope the Hillary Step isn’t fully collapsed or compromised, as I wanted to climb it some day!