There has been a lot of gushing editorial written recently to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the first American ascent of Everest in 1963. Rightly so, as it was a very successful expedition, thanks chiefly to the determination of two men, Tom Hornbein and Willi Unsoeld, who slipped up the West Ridge, a route which even today has rarely been climbed, then did a full traverse down the mountain’s “normal” route, the Southeast Ridge, rescuing two of their teammates on the way, Barry Bishop and Lute Jerstad who had also reached the summit that day but were struggling to descend. The expedition had been concentrating its resources on ascending by the normal route and three weeks earlier Jim Whittaker had become the first American to climb Everest, when he reached the top with Nawang Gombu Sherpa. Hornbein’s and Unsoeld’s ascent by a new route had been a sideshow to the main event, but it was a much greater achievement in mountaineering terms.

I could write a bit more about the expedition here, but I wouldn’t be adding anything to what’s already out there. Instead I’m going to talk about another expedition which took place on Everest’s north side three years earlier. One of the posts I read last week, 50 things about the 50th anniversary of the 1963 American Everest Expedition, lists many fascinating facts, like there were 909 porters, 10 tons of food packed into 416 boxes, the team members had 15 wives and 26 children between them and five had PhDs. As I was slowly drifting into a deep sleep one of the statistics caught my attention and made me sit upright in my chair, as I’m sure many of you have done in meetings.

“Only six people had ever stood on the summit before the American expedition — Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay in 1953 and four Swiss climbers in 1956, Ernst Schmied, Juerg Marmet, Dolf Reist and Hans-Rudolf von Gunten.”

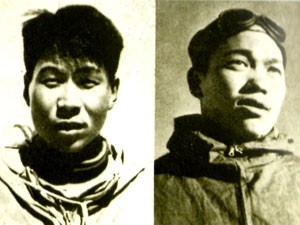

It caught my attention because it almost certainly isn’t true. Most official lists of Everest summiteers state that three climbers, Wang Fu-chou and Chu Yin-hua from the People’s Republic of China, and a Tibetan called variously Konbu or Gonpa (or perhaps Gombu), reached the summit from the north side in 1960. So why did the article state only six climbers reached the summit before the Americans? Did they mean only six climbers had reached the summit from the south side, or are they making a conscious decision to erase the Chinese expedition of 1960 from history?

When they announced they had made the first successful ascent of Everest from the north, the Chinese were greeted with scepticism in the West. Many of the incidents described in the report of their ascent seemed unlikely, even a little bizarre.

Here are just some of them:

- The four climbers who set out on summit day were Wang Fu-chou (a geologist), Chu Yin-hua (a lumberjack), Liu Lien-man (a fireman), all loyal members of the Chinese Communist Party, and Konbu (a Tibetan peasant). Most of them had only been climbing for two years.

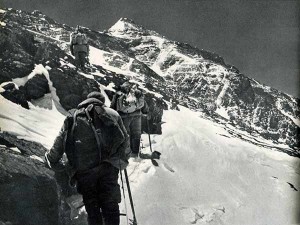

- They started out from a high camp at 8500m, which puts them firmly on the Northeast Ridge, probably on the slabs just beneath the First Step, although Mushroom Rock between the First and Second Steps is a possible location for a small campsite. Most expeditions these days set out from between 8200m and 8300m, well below the summit ridge where there is much more room for a campsite.

- It took them three hours to climb the Second Step. Liu Lien-man made four attempts to free climb it but kept falling. Chu Yin-hua then took his cramponned boots and thick woollen socks off to have a go, but also fell. They eventually got up when Liu used his expertise as a fireman to lift his teammates using the “short ladder method”. This involved standing on his shoulders as he crouched down to accommodate them. With a great effort he then stood up and enabled them to reach above and haul themselves on top.

- When Liu collapsed from exhaustion 100m beyond the Second Step, the three communists held an emergency meeting. They decided Liu would wait with an oxygen cylinder while the others continued to the summit. In Wang’s words “though he wasn’t with us his noble spirit gave us great strength to score the final victory”.

- It was dark when they reached the summit at 4.20am. By then their oxygen had run out and they completed the final stretch along the summit ridge on all fours with Konbu leading.

- They left a Chinese flag and a small plaster bust of Chairman Mao on the summit, together with a pencilled note containing their signatures under a small heap of stones. None of these items were there when the Americans reached the summit three years later.

- They descended during darkness, picking up Liu on the way. According to Wang they were successful because “it was the shining light of the Party and Chairman Mao Tse-tung who gave us the boundless strength and wisdom”.

The pompous Communist language probably didn’t aid the veracity of their story in the eyes of Western climbers, and there was doubtless some incredulity that the Chinese might succeed with novice climbers where seven earlier expeditions containing the cream of British mountaineering had failed. But despite the curious incidents that took place on summit day, members of the Chinese expedition were very open about their climb, and answered many questions about it in following years. These days their ascent is generally considered to be genuine and appears in official records. Here are some of the reasons why:

- Although they were novices they had followed an extremely rigorous fitness training programme, and their climbing experience included ascents of 6177m Nyenchin Tangla and 7546m Muztag Ata.

- Their statement about reaching the summit in darkness after running out of oxygen was perhaps the claim that seemed most implausible to people at the time. The editor of the Himalayan Journal left a snotty note against it in his published version of the Chinese account which read “it is, perhaps, necessary to point out that we cannot endorse this exÂtraordinary statement”. In 1960 nobody believed Everest could be climbed without oxygen, but many other climbers have done it since.

- Chu Yin-hua’s story about taking his shoes and socks off to climb the Second Step suddenly became more believable to American climbers who went to question him when he took them off again to reveal ten little stumps where his toes had once been.

- Chris Bonington questioned expedition leader Shih Chan-Chun at length and professed himself to be in no doubt about the ascent.

- When they completed the second ascent of Everest from the north in 1975, another Chinese team left a six foot metal tripod there which Doug Scott and Dougal Haston found when they completed the first British ascent four months later.

What convinces me most the Chinese ascent of 1960 must have been genuine was the route description in their official expedition account. While sometimes a little vague about the details it contains enough of them to prove they must have actually been there. [Note my source for this is Peter Gillman’s excellent anthology Everest: Eighty years of triumph and tragedy, which quotes Wang’s account in its entirety.]

- They describe scaling a one-metre rock on the way. Although the Third Step is higher than this in total, it consists of a number of obstacles which could fit this description to an exhausted climber ascending in the dark.

- They describe having to ascend an ice and snow slope in knee-deep snow. Their description matches that of the lower part of the summit pyramid immediately above the Third Step.

- They describe confronting a sheer ice cliff at the top of the slope and having to circle around it in a westward direction. This is exactly the route climbers follow today.

- They describe being overjoyed to reach a false summit, only to discover another peak a few metres higher on the other side. The final part of the summit ridge does indeed undulate in this way, and although the true summit can be seen from some distance away, this description is consistent with climbers approaching the summit in the dark.

We should remember that apart from George Mallory and Sandy Irvine, who may also have reached the summit along this route in 1924 but did not return to tell the tale, nobody had ever been that way before. If Wang and Chu had been making their story up it would have been a remarkable coincidence for them to describe features on the route in sequence without having seen them. They couldn’t have stolen the route description from someone else because it didn’t exist. I climbed the route myself last year, and sketchy as their account is on some of the details, there’s no doubt in my mind they were describing the route to the summit along the Northeast Ridge. They must have reached it.

So, sorry America, great as your 1963 expedition was, you have Everest’s 10th, 12th, 13th, 14th and 15th summiteers, but the Chinese got there first. You can console yourselves that we in Britain had many more expeditions, but we had to wait until Doug Scott, Dougal Haston and Pete Boardman became the 50th, 51st and 52nd summiteers in 1975. As far as I know none of them had PhDs.

Interesting read. It makes complete sense. Never really studied it before so Thanks Cheers Kate

Thanks, Kate. It’s one of those expeditions that not much has been written about, but historically it’s very significant.

LOL Mark, the politics of mountaineering 😉

Cheers, Dean. If only you had posted a few hours earlier I could have said hello to a few old friends of yours. I’ve just come back from Stephen Venables and Robert Anderson’s lecture at the RGS about their first ascent of Everest’s Kangshung Face in 1988. As well as Robert obviously (who was presenting but I didn’t speak to) I bumped into three more of your old Cho team mates, Matt, Mark P and Richard S, out of the blue in the bar beforehand.

Great article, nice to have comment by someone who has been there.I’d be interested in your view of the following theory.

The Chinese top camp was only 20 minutes walk from Malory’s body. Weather was good and two set off for the second step leaving three in the camp.

The two were unsuccessful in getting up the second step and after staying out the night returned to the camp. During this time Mallory’s body must have been found it has been admitted that his ax was picked up. Surely they have picked up his diary and his camera? The information could be invaluable in helping them Summit. They returned to base camp and had time for his diary to be read and translated. It told them the route to the summit, it described it. They returned and tried to conquered the summit maybe they were unsuccessful or maybe, as they said they did but were delayed and reached the summit at night and had no photographic proof. Some time later a photograph taken at 8700m was produced. Was this photo taken in 1924? Is the answer to this riddle hiding in plain site?

Hi Alec, slightly confused, but are you suggesting that before falling to his death George Mallory stopped on the Northeast Ridge to jot down the summit route in his diary?

I think it unlikely. But if they didn’t summit it may be the only way they could have produced the descriptions of reaching the summit, although the descriptions are sketchy.

The Chinese “proof” picture is poor and the framing strange although no one would expect a great picture from here. I think worth comparing this with pictures taken in the Chinese expedition and from the 1924 expedition.

The three Chinese left at the high camp during their first attempt at the second step would surely have found Mallory. They were very familiar with the 1924 expedition and surely knew who it was. If he had a diary and a camera I don’t think they would have left them. I’ve struggled to find any information about Mallory’s diaries, and what he tended to write in them. Was he in the habit of making notes during a climb, did he take one on a climb at all?

I’m puzzled why you prefer to invent a far-fetched conspiracy theory to explain the Chinese ascent, rather than accept the perfectly reasonable explanation that their route description is accurate because they did in fact reach the summit.

There is no chance George Mallory stopped on descent to write up his diary. He was fighting for his life to get down; it would have been the only case in history of a mountaineer prioritising his memoirs over safe descent. The high winds and extreme temperatures on the Northeast Ridge don’t lend themselves to producing a paper and pen and writing an essay. Do you think he kept his mitts on, or preferred to risk frostbite? Perhaps that’s why he ended up dropping his ice axe. 😉

I also think it’s extremely unlikely any climbers left at high camp will have found Mallory’s body. He had fallen to his death down steep slabs above a 3000m drop, after all, and it was 75 years and numerous expeditions before he was eventually found and identified. Much more likely they would have remained in their tents all day. It’s one of the most inhospitable locations on earth, and not somewhere you’re tempted to get out of your sleeping bag and risk your life by going for a wander.

“Tom: I knew nothing about this tent at first. When I was in Beijing interviewing the leader of the expedition, Mr. Ching and one of the summiteers, Chou Yin-Hua, we sat for many hours and discussed the events of 1960, and one of the things I asked them was “were any strange items found during your expedition in 1960?” And remember, this is the first expedition to the upper part of Mt. Everest on record since 1938.

There’s some talk of Russians going high in the early ‘50s, but my research into that has shown that that’s unlikely. So these guys were walking into an archeological minefield of things that had been lying there for all those years. And a couple of the things that they found were really intriguing. One of them was a camera, they found a camera on the trail going up to Advanced Base Camp.

It was an old camera, and they told me that they took the camera back to Beijing and developed the film and there were no images on the film. And then they told me that they found this totally bizarre discovery of a woman’s high-heeled shoe up there.”

http://www.mounteverest.net/story/stories/ExplorersWebinterviewwithThomasNoyJul92003.shtml

Now I see what is meant by the closing comment in “Ghosts of Everest” about new information “perhaps” coming out of China. It would be interesting to know if this camera still exists. Highly interesting.

Heehee, perhaps Maurice Wilson was the first person to climb a Himalayan peak in stiletto heels! 😉

Thanks for the interesting article. Everest has always fascinated me and I enjoy reading all I can on the subject. I have to agree with you that the Chinease did make it!

Everest climber Xu Jing claim that he found an old body high up on Everest during the 1960 expedition, if true, then it could have been none other than the body of Andrew Irvine. The significance of this claim if true is huge from an historical point of view.

Why did Xu Jing not take a photograph of this body to back up evidence of his claimed sighting. It is extremely difficult to believe that Xu Jing did not realize the significance of this claimed sighting. This is pure speculation but picture this scenario. Xu Jing did in fact discover the body of Andrew Irvine, and may or may not have taken photos. The Chinese took the camera that Irvine had. They buried his body.

The Chinese expedition of 1960 may or may not have reached the summit of Everest.

Mallory and Irvine’s camera was returned to China and photographs were developed that

conclusively and emphatically showed that the first summit of Everest did occur in 1924

via the North East Ridge route. So perhaps what we have here is a case of Chinese

propaganda. In conclusion perhaps with the knowledge of a successful summit in 1924

the Chinese suppressed the evidence in order to establish themselves as the first

successful expedition to reach the summit of Everest via the North East Ridge route.

Pure speculation of course but it is not beyond the realms of possibility either.

Or then again, perhaps what we have here is just another conspiracy theory … 😉

Yep, just another conspiracy theory.!! The Chinese description in reference to “The Conquest of Everest by the Chinese” of their ascent of the second step does seem impossible given the altitude, the extreme cold, and the difficulty of the terrain. These feats if true are not only heroic but also extremely altruistic. Its a great pity these feats do not have photographic evidence in order to document the seemingly impossible physical challenges that would be difficult even at sea level. There is a reason why the Chinese affixed a ladder to the second step in 1975.!! Skepticism is healthy and of course part of human nature. I guess we just have to take their word for it.!!

The Chinese did not reach the summit of Everest in 1960, via the North East Ridge. Surely any individual with even a modicum of rational thought and insight would arrive at the same conclusion. The story that they provide is simply not believable from any rational perspective. No human being would of survived or have successfully summited an attempt on Mount Everest under the circumstances that they have provided in their “Conquest of Everest” literature. It is just not believable from any reasonable aspect. Many may be critical of this opinion, but that criticism would turn to rationalism in the blink of an eye when, if they themselves were faced with the harsh and brutal “Realities” of the nature of the beast which is Mount Everest.

Thank you for your input, Michael. I have faced the “harsh and brutal realities of the nature of the beast which is Mount Everest”. Have you?

You might also like to read John Cleare’s comment about his meeting with Chu Yin-hua here:

https://www.markhorrell.com/blog/2012/what-climbing-everest-taught-me-about-george-mallorys-final-hours/#comment-163923

The conspiracy theory that the Chinese stole Irvine’s camera to pass off its photos as their own is not plausible. Consider the fragile chain of events required to make it true.

First, the Mallory/Irvine expedition would have had to succeed in reaching the summit. Then, Mallory would have had to write down his exact route. Then, the Chinese would’ve had to find the camera. Finally, the Chinese would’ve had to develop the film successfully and pass it off as their own.

But suppose the Mallory/Irvine expedition had failed to reach the summit? Suppose Mallory didn’t write down his route? Suppose the Chinese didn’t find the camera? Suppose the film had fogged up after 36 years of exposure to cosmic rays? Did the Chinese take the necessary precautions when developing the film? (Kodak gave very detailed instructions to Tom Holzel before the 1986 search expedition. The Chinese would not have had access to Kodak expertise in 1960.)

Take away any link in the chain, and the whole conspiracy theory collapses.

The conspiracy theory is not even the likeliest chain of events given the premise. Suppose that Mallory/Irvine had succeeded in 1924. Doesn’t that actually bolster the Chinese claim, as they were using 1960s Swiss mountaineering equipment?

Mark, thanks for another enjoyable article. I was also looking at your “What climbing Everest taught me about George Mallory’s final hours” and wondered, while looking at the picture of the Third Step and the red marked route of ascent, what would happen if one continued up the snow slope as this seems to be a logical route without the benefit of hindsight. The Chinese went this way, found an ice cliff, and circled around it. All very interesting.

The photo is deceptive. As you point out, at the top of the slopè there is a wall and you have to skirt to the right along rock ledges. This is one of the points that persuaded me the Chinese description of the climb is authentic, as I had to do the same thing when I got there.

Well, as a Chinese。I need to say,from the document and memoirs of Qu Yinhua,.When they reached the Everest , it is already 4:20 AM of May 25th,1960.It is very dark and they didn’t take any light (because in the first they did not plan to reach the top in the night)and night vision camera . So they left a container with date and national flag on the Everest.

Well,some people questioned that the Chinese people didn’t reach the top, perhaps because bias?

The Chinese can have their 1960 summit due to the “shining light of the party” America still has the first summit of the F—ing Moon!……..and we have our flag our there to prove it.LOL

Isn’t there a conspiracy theory about that one too?

Maybe they were under severe political pressure to succeed. The build up to the cultural revolution wasn’t far off. Failure to summit might have led to disgrace or far worse; people had been arrested for less. If they didn’t make it, maybe a decision was made to lie about what happened and avoid the consequences. They were certainly brave in making the attempt when they did.

Pingback:The Climbers: Wu Jing and Jackie Chan in New Everest Movie

Pingback:A polêmica de 60 anos: Os chineses realmente chegaram ao Monte Everest em 1960?

Pingback:Review: "The Climbers" Is a Birthday Present for the People's Republic of China's 70th Birthday | Cinema Escapist

Pingback:The Team to Follow on Everest this Year – Explore 7 summits

Hi Mark, thank you so much for writing about this Chinese expedition! My late grandfather, Wang Mingus, is with Christ now, but he was a geomorphologist who went on this expedition. Growing up, we would listen to him share stories, like how only two people from his team actually summited Mt. Everest, and a couple others had unfortunately died along the way, including a man who’d helped to carry my grandpa on his back one day when he had no energy. He did mention that they had come across the body of a British explorer.

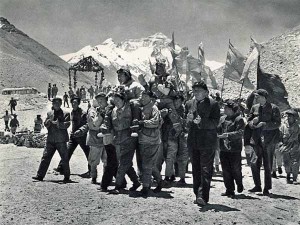

My sister is having a mountain and adventure-themed baby shower this weekend for my soon-to-be nephew, Everest, named in memory of my grandfather and his adventurous spirit. I was researching this expedition to see if I could find a few factoids to share with the guests. As you mentioned in a previous comment, not much has been written about this expedition- at least not much that I can find on the web. Reading your article was refreshing, as it brought me back to the stories that my grandpa would share. I’d also never seen those photos before, so thank you for sharing those! I’ll have to show my parents to see if they’re able to identify him. Thank you again and God bless.

Apologies, autocorrect changed my grandpa’s name. His name was Wang Mingye. Thank you again, Mark!

“Everest climber Xu Jing claimed that he found an old body high up on Everest during the 1960 expedition, if true, then it could have been none other than the body of Andrew Irvine. The significance of this claim if true is huge from an historical point of view. Why did Xu Jing not take a photograph of this body to back up evidence of his claimed sighting. It is extremely difficult to believe that Xu Jing did not realize the significance of this claimed sighting. This is pure speculation but picture this scenario. Xu Jing did in fact discover the body of Andrew Irvine, and may or may not have taken photos. The Chinese took the camera that Irvine had. They buried his body. The Chinese expedition of 1960 may or may not have reached the summit of Everest .Mallory and Irvine’s camera was returned to China and photographs were developed that conclusively and emphatically showed that the first summit of Everest did occur in 1924 via the North East Ridge route. So perhaps what we have here is a case of Chinese propaganda. In conclusion perhaps with the knowledge of a successful summit in 1924 the Chinese suppressed the evidence in order to establish themselves as the first successful expedition to reach the summit of Everest via the North East Ridge route. Pure speculation of course but it is not beyond the realms of possibility either.”

Hi, Mark.

I wrote the above on October 15, 2014, at 2:09 pm. At the time I wrote that comment, it was pure conjecture. Now it seems “possible” my statement has a ring of truth.

https://www.sundaypost.com/fp/mount-everest-conspiracy/

Synnott was part of an 18-strong expedition led by the New Zealander Jamie McGuinness. He revealed: “One of his local contacts told Jamie that he had heard directly from a China Tibet Mountaineering (CTMA) official that the Chinese had beat us to the Holzel Spot and carried Irvine’s body off the mountain and back to Lhasa, where it is kept under lock and key with other Mallory artefacts, including the VPK.”

Synnott accepts that the information is only hearsay, but in the book, he stresses: “We now have multiple sources all essentially saying the same thing: the Chinese found Irvine, removed the body, and are jealously guarding this information from the rest of the world — all to protect the claim that the 1960 Chinese team was the first to reach the summit of the Third Pole from the north.”

Thank you.

Yes, as you say, pure speculation. I’m aware that a book was published last year that raised the theory that Irvine’s body and camera were recovered by a Chinese team and the events suppressed. But without hard evidence this is little more than a conspiracy theory and I would take it with a pinch of salt.

The suggested motive is also weak. Everest had already been climbed by 1960. Given the suspicions raised about the 1960 Chinese ascent at the time, why would the team want to suppress evidence? The discovery of Irvine’s body and camera would have been a major coup for them.