I love Nepal. Not only has it provided me with many great experiences and miles of wonderful mountains to travel through over the years, but it also gives me lots to write about. For example, as I reported in last week’s post, its government has made a number of bizarre announcements in connection with mountaineering that have provided content for this blog. A split second after I hit the publish button last week on my post about Nepal’s top-earning mountains for permit fees, its government made another of its eccentric statements about, you guessed it, permit fees.

The media picked up the gauntlet with stories around a common theme:

- Government slashes mountaineering fee to attract more climbers cried Kantipur, a Kathmandu daily

- Nepal to reduce fees to climb Mount Everest reported Reuters in India

- Nepal announces major revision of mountaineering royalties said the Japan based Kyodo News

- Nepal slashes cost of climbing Everest grunted the Guardian in the UK

All of them focused on a single detail of the Nepal government’s revision of the permit fee structure: that the price for an individual climbing Everest will be cut from $25,000 to $11,000. Overcrowding on Everest has been a favourite theme of the mainstream media in recent years, and on the face of it this detail seems certain to make the situation worse, but in reality the story is a little more complex. Permit fees have been revised not just on Everest but all mountains in Nepal, cheaper permits are available for Nepali nationals, and the group permit system which provided discounts for larger teams has been abolished. This latter point means that for larger expeditions permit fees haven’t been slashed at all, but have in fact increased from $10,000 to $11,000 per person. The seasonal pricing structure remains, where autumn and summer/winter permit fees are half and quarter the cost of spring season permits respectively.

The new fee structure was published in the Nepal Gazette, a regular government bulletin, and it is due to come into force on 1 January next year. In the meantime the current fee structure can still be found on the website of the Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation.

I have compared the new structure for the spring climbing season with the existing one in the table below. The last 2 columns are a simplified version of the current fees, which operate on a sliding scale for teams of 1 to 7 or more people. I have shown just the maximum and minimum figures.

| Mountain | Spring 2015 |

Individual 2014 |

Team member 2014 |

| Everest Normal Route | 11,000 | 25,000 | 10,000 |

| Everest Other Route | 10,000 | 15,000 | 10,000 |

| Other 8000m peaks | 1,800 | 5,000 | 1,500 |

| 7500m | 600 | 2,000 | 500 |

| 7000m | 500 | 1,500 | 400 |

| 6500m | 400 | 1,000 | 300 |

| Less than 6500m | 250 | 400 | 200 |

As you can see, for team members it hasn’t changed much, bar a slight increase. So what’s the purpose of these changes? The government’s motives aren’t always obvious, so I’ve pulled a few quotes by government officials out of the articles listed above.

“The move is aimed at attracting and encouraging more individual climbers in the country. We have revised the fee as there were numerous complaints from foreign mountaineers that climbing cost was too high in Nepal.”

“The change in royalty rates will discourage artificially formed groups, where the leader does not even know some of the members in his own team. It will promote responsible and serious climbers.”

“Since more people will go to remotely located mountains, locals will get jobs and income.”

“The new royalty structure eliminates incentives to add as many members as possible to an expedition team.”

“We brought about this change after seeing widespread malpractice. We have seen that in order to reduce the royalty cost per member, separate expeditions with separate team leaders managed by different organizers decided to go as one group. But once they are at the Mt. Everest Base Camp, the teams split and operate independently. The new royalty structure eliminates such problems as it discourages team mergers. Also, it makes climbing affordable for serious and professional climbers who do not want to be part of a group of strangers. I think many climbers who were put off in the past by the high climbing fees will now consider climbing our mountains.”

“Nepali climbers cannot afford the climbing fees set for foreigners. Till now, they had the choice of either waiting for months to get a waiver from the government or climbing mountains as guides of foreign climbers.”

From these quotes several clear reasons for the changes emerge:

- To encourage more climbers to come to Nepal

- To encourage climbers to visit lesser-known mountains

- To make mountaineering affordable for Nepali nationals

- To encourage more responsible climbers

- To encourage more people to climb individually or in smaller groups, rather than as part of larger teams

The first four of these do not need a great deal of discussion. They are positive reasons that will help to generate income from tourism, reduce the impact of tourism by dispersing climbers to different areas, and improve the quality of life for local Nepalis. Whether the new fee structure will achieve these aims is less certain (and in the case of no.4 it may well have the reverse effect as we will see) but I have no problem with any of these motives.

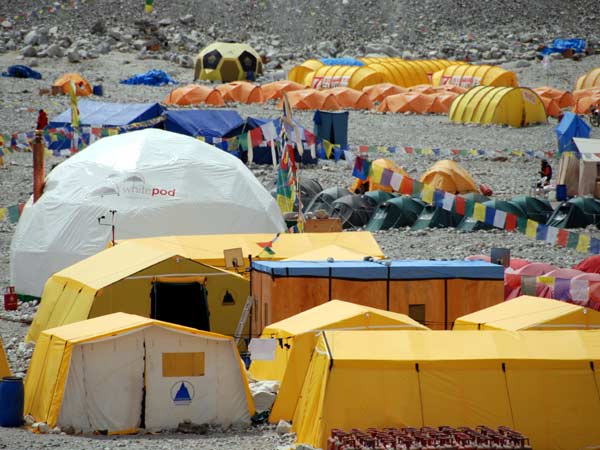

But reason no.5 is another matter. This one sticks out like a bacon sandwich at a bar mitzvah. The target appears to be maverick climbers who club together as a team in order to get cheaper permits, but climb independently once they get to the mountain and take no responsibility for each other. These people tend to climb on the cheap, are poorly organised with little support and few contingencies when things go wrong. They will clip into ropes that have been fixed by other teams, and climb without tents and equipment because they have no qualms about using other people’s when they find them unused in higher camps. Some of them even steal oxygen and fuel from the higher camps of better prepared teams, putting lives at risk. Because they are an assortment of individuals rather than a team, they abandon each other when one of them gets into trouble. Instead it is often the larger, better organised teams who find themselves diverting their resources to help out in the event of an emergency.

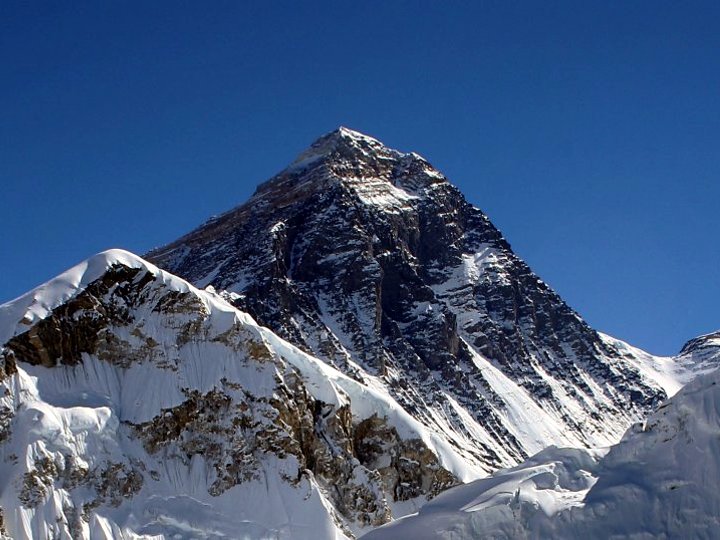

These maverick climbers were common on the north side of Everest a few years ago, when permit fees for Tibet were only $4,000 per climber and $800 for a Sherpa. When I climbed to the North Col of Everest in 2007, base camp was a small town of tents, and almost an equal number of climbers summited from the north side that year as they did from the south. Some expedition leaders operating in those years described the atmosphere as being like the wild west, and the nadir came in 2006, when eight climbers died in separate incidents, many of which were preventable and some quite foolish.

But since 2008 the Tibetan side of Everest has undergone a change. That year the Chinese government closed the mountain to foreigners while it (allegedly) took the Olympic torch to the summit in controversial circumstances, and since then permit fees have increased dramatically. When I summited from that side in 2012 the permit fee was $7,300 for a tourist and $3,000 for a Sherpa (which effectively meant I paid $10,300). There were very few of the mavericks remaining; base camp felt like a ghost town compared with how I remembered it in 2007, and it was relatively quiet on summit day. Meanwhile the queues on the south side were attracting headlines worldwide.

I think you can see where this is heading: right diagnosis, wrong cure. The Nepalese government is right to discourage the mavericks and freeloaders, but they’re not going to achieve it by abolishing the group permit fee. The mavericks will still come; it’s just that they won’t have to club together for a group permit any more. They can pay separately. It probably means there will be more of them in future years, like there used to be on the north side. It’s a bit like curing angina by ripping out the heart.

“These changes open the possibility of individuals going up without being part of a big team any more. I find that terrifying frankly; safety comes from being in a team,” Simon Lowe, managing director of the UK mountaineering company Jagged Globe was quoted as saying in the Guardian. Jagged Globe are one of the larger teams operating on the south side of Everest, and they managed to achieve an impressive 100% success rate on their last two expeditions there.

“It’s all bullshit. The south side permit was $70,000 for seven, at $10,000 each. Now it’s $11,000 each. Stupid fuckers at the Ministry of Tourism,” another successful expedition operator told me (who shall remain anonymous, and strangely, wasn’t quoted in the Guardian).

This year could be a good one to visit the south side of Everest, as next year may well be The Return of the Mavericks.

This has been a bit of a rant, so I’m going to end by making a practical suggestion. I’m not one of those people who believe Everest should be the preserve of elite climbers only (I’d be a bit of a hypocrite if I did, or otherwise have a staggeringly deluded opinion of my own abilities). I quite like the fact that the world’s highest mountain is an achievable aim for anyone with the necessary determination and patience to succeed.

The concept of prequalification to climb Everest has always been controversial, but perhaps some of the Nepali government’s other, more positive, objectives could be met if there was. Presenting a certificate to say you have climbed another 8000er in Nepal may help to filter out some of the mavericks, and it would certainly help to filter out those without patience or experience, thus encouraging climbers who are more responsible. People are always going to want to climb Everest, there’s no getting away from it, but more of them would be distributed around other mountains in Nepal. More foreign climbers, more mountains, more income for Nepal, and perhaps more Nepalis climbing as well. Has the time come?

This would take care of climbing experience to some degree, but that’s only part of the story. The real problem with the mavericks is not their ability to get up and down a mountain, but that many of them fail to take responsibility as expedition organisers. This means arranging the necessary logistics and ensuring the expedition is appropriately equipped, taking care of their environmental footprint and making sure waste is packed out, ensuring any staff employed have the necessary experience, are paid fairly and insured in the event of an accident. And of course they need to take responsibility for the safety of their team, and be willing and capable of looking after them should anything go wrong. It’s unclear how abolishing the group permit fee is going to help with any of this.

Ever increasingly bizarre announcements is about right:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-26285028

Phil

Ah, yes, that old chestnut:

https://www.markhorrell.com/blog/2013/the-neweverest-base-camp-police-force/

(Though I wonder how far the BBC and others are pushing the “stopping the high-altitude brawling” angle…)

Haha! I see!

Thanks to the other Phil for the BBC story above, a useful read.

Further to my comments last week about the global economic causes for the decline in expeditions, in light of Mark’s points on this subject (Maverick climbers), one wonders just what (if any) co-ordination in policy between the Nepalese and their Chinese opposite numbers there is in relation to this matter and if not, whether its time a more coherent joint policy between these nations would be useful?.

tickity boo chaps,

Philip

Hi Philip,

That’s an interesting question, and the Chinese government have shown they are powerful enough to enforce rules on both sides of the mountain. In 2008 they closed the north side completely to foreign expeditions while they took the Olympic torch to the summit, and the Nepalese government allowed them to station gunmen in the Western Cwm on the south side to stop anyone climbing higher than Camp 2 before the torch reached the top.

But this was a one off which seems unlikely to happen again. The two countries have very different priorities with regard to Everest. For the Nepalese it is essential to the local economy, bringing much needed income to the many porters, guides and tea house owners en route to base camp. But for the Chinese I almost get the impression they don’t want climbers there, but put up with them because it would be more of a diplomatic issue to ban them entirely than allow them in and enforce a few rules. They were happy to close Everest in 2008, and there are often last minute permit issues on Cho Oyu and Shishapangma which cause operators to baulk at running expeditions there.

While it might sound sensible for both governments to coordinate the rules given that expeditions to both sides use Kathmandu as their home base, in reality once climbers get to base camp they could be climbing two different mountains.

Regards,

Mark.