This is part 5 of a series of posts about early tourism in Nepal. For the previous posts see part 1: How Nepal first came to open its doors to tourism, part 2: Bill Tilman: Nepal’s very first trekking tourist, part 3: Tilman’s expedition to Langtang, and part 4: Tilman’s expedition to the Annapurnas.

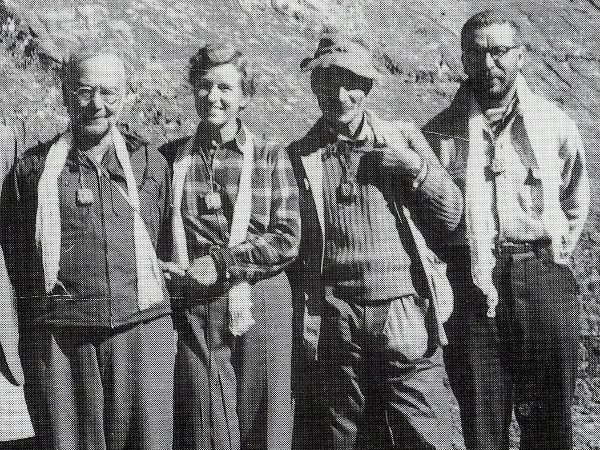

The great mountain explorer Bill Tilman made three treks in Nepal in 1949 and 1950. His third, to Everest, came about quite by chance. When he returned to Kathmandu after his extensive exploration of the Annapurna region in 1950, he bumped into an old American friend Oscar Houston at the British Embassy. Houston was about to depart on his own five-week bummel around Nepal (Tilman’s word, not mine) with his son Charles and two family friends Anderson Bakewell and Betsy Cowles.

Both Houstons had been on the Nanda Devi expedition with Tilman in 1936, when Tilman and Noel Odell reached the 7816m summit of what then was the highest mountain ever climbed, but Tilman sent the older Houston home early because he doubted his fitness. Charles Houston was himself a mountaineer of some repute, who led two momentous expeditions to K2 in 1938 and 1953, and would himself have made the first ascent of Nanda Devi with Odell had he not contracted food poisoning the day before their summit attempt and been replaced by Tilman.

Luckily for Tilman, neither Houston bore him a grudge, and Oscar invited him to join them on their short trek to the Solu-Khumbu. Having been so long in Nepal, Tilman considered declining the kind invitation, but he felt he would be a fool to turn it down because until then no westerner had been granted the opportunity to explore Everest from the south. Tilman knew Everest well from the north. He had been a member of Eric Shipton’s 1935 monsoon reconnaissance, during which he made several first ascents of neighbouring peaks, and he led the 1938 expedition, where he climbed high up the North Ridge.

It wasn’t just the opportunity to explore Everest from the south that intrigued Tilman. He observed, there was also “fun to be expected from seeing Sherpas, as it were, in their natural state”. By this he didn’t mean he wanted to see them naked, but that it would be interesting to visit them in their ancestral home of the Solu-Khumbu.

These days most visitors to the Khumbu region have to endure the hair-raising flight into Lukla, a means of transport that became even more scary last month after it emerged the airport’s wind anemometer has not been working for three years, and authorities have not repaired damaged fencing wire for over a year, allowing deer and dogs to stray onto the runway.

Tilman’s party were able to make a more leisurely approach. They trekked in from Biratnagar in the far southeast of Nepal, through the small town of Dhankuta, where a message chalked in English on a Hindu shrine left a great impression on them.

“Gather courage, don’t be a chicken-hearted fellow,” it read.

From here they dropped to the sticky low-altitude jungle of the Arun Valley before heading across country over a series of smaller valleys and passes, to arrive into Lukla near what is now the Zatr La pass, which trekkers and mountaineers cross on their way to and from Mera Peak. Tilman described reaching Namche Bazaar as his pilgrimage to Mecca. He would have heard stories often from Sherpas and must have been intrigued to visit. It wasn’t the hive of teahouses and four-storey hotels it is now, but he noted that it appeared more wealthy than Manang, the town he visited in the Annapurna region a few months earlier. In Namche he found a handful of detached homes clustered round a cwm, rather than being all huddled together as they had been in Manang.

Namche wasn’t his main objective, though. He and Charles Houston had only a few days to reconnoitre a route up Everest from the south. They quickly moved on through Tengboche, where Tilman was pleased to discover monks at the monastery “had the pleasant custom of fortifying their guests with a snorter for breakfast” (I think he meant alcohol, not cocaine).

As things turned out, they had only two days to explore a possible route up Everest from the south. On the first day they decided to climb up to the Lho La, the high pass above today’s Everest Base Camp, which crosses into Tibet. George Mallory reached it from the north during his 1921 reconnaissance, and looked down into the narrow valley which approaches Everest from the west, naming it the Western Cwm after the Welsh valleys of Snowdonia he had explored in his student days.

Tilman knew there were two keys to climbing Everest from the south. Firstly there needed to be a practical route from the top of the Western Cwm to the South Col, which lay between Everest and Lhotse to its south. Secondly, there needed to be a route up the ridge from the South Col to Everest’s summit.

Tilman and Houston’s first exploration proved disastrous. As they climbed up to the Lho La a trick of the light prevented them even seeing a route into the Western Cwm up the Khumbu Icefall, a narrow gap which they spotted easily the following day. On the second day they decided to climb Kala Pattar, now a well-known viewpoint on the Everest Base Camp trail. Here they discovered what many trekkers now know: from this viewpoint the South Col is obscured by a shoulder of Nuptse, a ridge protruding west from Lhotse, which appears as a striking snow pinnacle from Kala Pattar. With the South Col hidden from view there was no way of knowing whether there was a possible route up from the Western Cwm.

The second question – whether there was a route from the South Col to the summit – also proved elusive. From Kala Pattar Tilman thought the south ridge of Everest looked horribly steep, but he concluded correctly that he wasn’t looking at the ridge but a buttress protruding from the Southwest Face. In fact Everest’s southern approach is not a south ridge, but a southeast one which is not as steep as the angle looks from Kala Pattar.

Their reconnaissance proved inconclusive: they couldn’t say whether the South Col could be reached from the Western Cwm or the summit could be reached from the South Col, but neither could they say it couldn’t. Tilman didn’t particularly give a toss about this – they had done their bit for exploration and others would follow. Not everyone saw it so casually, and it would be Tilman’s old friend and travelling companion Eric Shipton who would answer the remaining questions on another reconnaissance the following year.

By 1950 the British had made seven expeditions to Everest and weren’t getting any nearer to the summit, and although they didn’t know it their monopoly on Everest was over. The Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1950 ensured the route from the north side would be closed to westerners for many years, but the south side through Nepal was now open for business. A young mountaineering doctor called Michael Ward was so concerned the British would lose the race to climb Everest that he scoured the archives of the Royal Geographical Society and discovered some photos of the Southeast Ridge which had been taken during covert flights over Everest in the 1940s. The photos showed a practical route to the summit from the South Col. This meant if they could get through the Khumbu Icefall and up to the col then Everest could be climbed from the south.

Ward persuaded the Mount Everest Committee, which had been renamed the Joint Himalayan Committee, to part-fund a reconnaissance expedition to the Khumbu region in 1951, led by Shipton. Shipton and Edmund Hillary climbed up a shoulder of Pumori soon after reaching base camp, from where they could see a route up the Lhotse Face to the South Col. Now they just needed to get through the Khumbu Icefall. They very nearly succeeded, but were turned back by a giant crevasse just as they reached the Western Cwm. It was left to Rayment Lambert’s Swiss team to find a way over the crevasse the following year, and Hillary and Tenzing to reach the summit in 1953.

Tilman’s 1950 reconnaissance would be his last visit to the Himalayas, the place that had made his name as an explorer and left him with many fond memories, but the history of trekking in Nepal was only just beginning.

Next – Colonel Jimmy Roberts and the first ascent of Mera Peak.

Another interesting post. Keep them coming!

Thanks, Robert. I will. 🙂

Thanks for another great post!

I love reading all your posts about mountaineering/expedition/trekking history.

I’m also looking forward to your book. 🙂

Thanks, Ann. I’m very happy that you’re looking forward to the book. It will be much better than my blog posts, I promise, and with you and my father I now have at least two readers!

In many recounts since, authors give the impession of blaming Tilman and Houston not to have climbed a little higher (like Shipton did with Hillary in 1951). A quite different information I found in Peter Steele’s Shipton-biography “Everest and Beyond” (p.143), who states “classical symptoms of early […] high altitude cerebrial oedema” at least for Houston, and Tilman “swore he would never go high again; and indeed he did not.”

Another forgotten fact: In 1951 the first people to tackle the Khumbu Icefall were New Zealander Earle Riddiford and Pasang Dawa Lama (while Shipton and Hillary had their famous view along the Western Cwm). It was their part of the group’s work, being well acclimatized after the NZ Garhwal expedition. Both Murrays report in Himalayan Journal and Shipton’s report in Geographical Journal confirm this. It’s amazing that later recounts do not mention especially Pasang Dawa Lama’s role in the events – sometimes as a leading climber, let alone refer to his exceptional skills shown in 1937 (Chomo Lha Ri), 1939 (K2), 1954 and 1958 (Cho Oyu), and on Dhaulagiri throughout the 1950s.

The narrative, I think, is too much dominated by the “heroes”, and focussed on the “heroes”, like Hillary (who, in this case, disliked both Riddiford and Pasang).

Thank you for this blog, Mark!

Thanks, Ulrich – another gem.

Have you read Tichy’s Cho Oyu? Pasang Dawa Lama is very much the star of the book in a way I’ve seen no other Sherpa presented in any other book.

I reviewed it last year:

https://www.markhorrell.com/blog/2015/battle-of-the-blockbusters-herzogs-annapurna-vs-tichys-cho-oyu/